They're driving us right into a crisis.

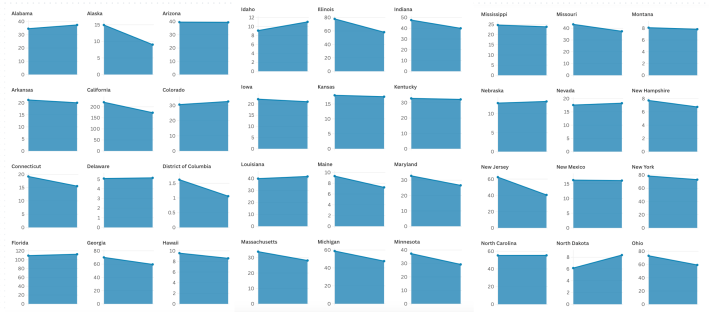

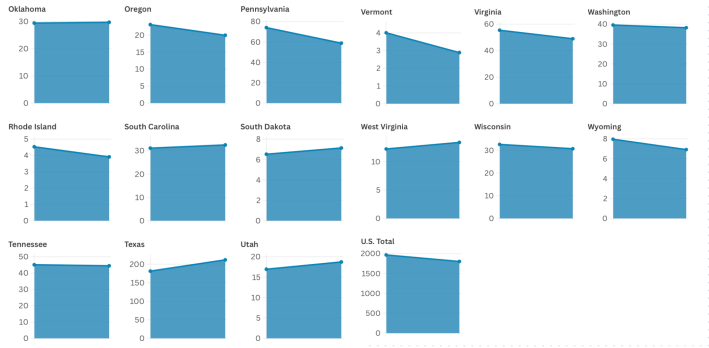

Fourteen states actually increased their transportation sector emissions between 2005 and 2022 — despite a 30-percent leap in average vehicle fuel efficiency over that period and a 25-percent national decline in per-capita emissions overall, a new report finds.

According to EPA estimates compiled by Environment America, not only did the transportation emissions rise in the Filthy Fourteen, but emissions were essentially flat in another five states, including Arizona and New Mexico.

The list of high-polluting states included Alabama, Florida, South Carolina, and a raft of other red states that successfully sued to stop a federal rule that would have required them to simply self-report their transportation emissions levels, even though that rule did not require them to reduce pollution. That move was supported by House Transportation Committee Chair Sam Graves (R–Mo.), who was reportedly on President-elect Trump's short list for Transportation Secretary, and who pledged to overturn the rule had it gone forward.

The Environmental Protection Agency already collects state-level transportation emissions stats of its own, but it's released in a form that isn't easily legible to the public who pays for polluting infrastructure, at least until advocates do the hard work of digging through it all.

The red state lawsuit aside, though, it's worth noting that blue states like Colorado and Delaware were on the list of states that increased their transport emissions, too. Most states where transportation emissions decreased, meanwhile, still aren't on pace to meet our national goal of slashing 50 to 52 percent of 2005 levels by 2030.

And the report authors did not mince words about what that should meant for policymakers who have over-relied on improvements in power sector emissions to meet their climate goals.

"Emission reduction efforts will need to target the transportation seector, now the largest source of pollution in half of the 50 states," they wrote. "Options include rapidly replacing polluting internal combustion engine vehicles with electric vehicles, as well as investing in improvements that make walking, biking and transit more convenient and practical, thus allowing people the option of driving less."

Of course, how much weight America gives to each of those "options" matters deeply — especially in this uncertain political moment.

Even if rapid vehicle electrification alone were enough to decarbonize the transport sector – and many experts argue it's not — the incoming Trump administration is reportedly poised to kill the EV tax credits that would help make it possible. The president-elect has also been clear about his intentions to rapidly expand oil production under his proposed Secretary of the Interior, Doug Burgum, who despite a few viral urbanist soundbites, is still the governor the only state in the country that increased overall per capita emissions over the course of the study period: North Dakota.

A recent Union of Concerned Scientists report found, though, that "visionary but feasible" policies that reduce how much Americans need to drive would not only put states' transportation sector goals within reach, but would save U.S. residents a staggering $5.9 trillion in vehicle-related expenses, in addition to trillions in new energy infrastructure communities wouldn't have to build to power all those new EVs.

And many of those policies can be enacted cheaply at the state and local scale, without much collaboration from Washington — if transportation leaders are willing to finally take responsibility for their role in the climate crisis, and finally take action to do better.