History knows the Selma-to-Montgomery Trail as the site of some of the most famous moments in the America's civil rights movement, including Bloody Sunday, when state troopers brutalized more than 500 protestors as they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge. That outrage would inspire 25,000 more to join those protestors on a five-day, 54-mile march that ended with a now-immortalized speech from Martin Luther King Jr. at the Alabama state capitol — and eventually, the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In the years since that victory, though, the Alabama state highway authority — led by a director who was also the leader of a local Klu Klux Klan chapter — carved interstates 65 and 85 directly through the neighborhoods in which many of those activists lived, enacting what many say is tantamount to revenge on a vibrant community that was poised to spur even greater social change. Over 1,700 families were displaced in the process, 75 percent of whom were Black — and in many ways, the region has never fully recovered, even as the historians have moved on.

"That was not by accident," said Steven Reed, Montgomery's mayor, in an interview with Streetsblog at the Bloomberg CityLab conference in Mexico last week. "That was done intentionally by the state highway department at that time, because so many of the boycott and voting rights leaders lived in this area."

Last March, Reed's city won an opportunity to heal at least some of that wound: a $36 million grant from the Neighborhood Access and Equity Grants program, which will add bike lanes, sidewalks, and other mobility infrastructure along the trail.

It's the largest federal grant in the city's history, and in many ways, it's emblematic of a highly unique moment in America's transportation trajectory.

Under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Inflation Reduction Act, local leaders have been handed direct invitations to apply for an unprecedented level of discretionary grant dollars typically reserved for states — without having to pass local sales taxes and bond measures that their residents might find divisive. That war chest, though, is only available to them if they can navigate the labyrinth of the federal application system, and beat out the countless other communities with whom they're competing.

That can be a particularly tall order for small and mid-sized cities, many of which don't even have a dedicated grants director, never mind the deep technical knowledge and grant-making vocabulary that can tip a proposal into the "selected" column. In some communities, fire department heads, transit supervisors and even city clerks have found themselves writing complex applications for new infrastructure — and found their proposals up against large cities with whole grant-writing departments and decades of collective experience.

That's why Reed turned to the Local Infrastructure Hub, a free initiative that's helped around 1,600 small to mid-sized municipalities navigate the ins and outs of the application process, and turn their community's forgotten stories into grant-winning success.

"[This program gave us] a level of expertise, an opportunity to talk with subject matter experts who had come out of big administrations ... and really tell our story in a way that was unique and would be attractive to those at the federal level," he added. "I know we wouldn't have gotten [this grant] without this type of boot camp."

And Reed isn't alone. The Local Infrastructure Hub says participants have won a collective $2.5 billion in funding so far; participants who won Reconnecting Communities grants took home awards that were three times larger per resident than other city winners nationally.

"What we're really just trying to do is provide them any technical assistance we can, whether that's data competencies, community engagement strategies or something else," said Jamie Lavin, senior program manager of the Government Innovation program at Bloomberg Philanthropies, which leads the Hub initiative. "Send us your draft application, and we'll help you. We'll review it and give us some pointers, help you beef it up so that you have a fair shake at the money."

According to Lavin, unsuccessful applications for discretionary grants outnumber successful ones by a ratio of four to one — and not because the losing cities are short on powerful stories.

In Columbia, Missouri, for instance, Mayor Barbara Buffaloe was moved by the story of Louis Estrada Jr., who was struck by a driver while crossing a 30 mile per hour road called Clark Avenue on a December night. Louis, who had fallen into homelessness in the months before, was just two days away from moving into an apartment when he was killed; he never got the chance.

"I think about Louis a lot, and I think about like the improvements that we need to make for those who have been left behind," Buffaloe said. "These grants that we're getting from the federal government are one way we can help people like him."

Buffaloe, who spent 11 years as her city's sustainability manager before assuming office, stresses that the funding on offer to local municipalities now can help them improve safety while reducing emissions, increasing social mobility, and much more.

With the Hub's help, Columbia has won grants from not one, but three different federal programs in different years: a RAISE grant to upgrade the city's bus network, a Reconnecting Communities and Neighborhoods Program to study a complete streets redesign on the notoriously dangerous Business Loop 70 that rings much of the downtown, and a grant from Safe Streets for All, which will help Columbia plan a raft of street safety improvements which might save people like Estrada.

That's a stunning haul for a city of 126,000 people.

"Every city is understaffed," added Buffaloe. "We're all desperately trying to recruit police officers and bus drivers and other bare necessities; we just created our first grants administrator position last year. And so what the Local Infrastructure Hub did for us was that capacity-building that is just so desperately needed across all cities. It gave us hope."

"Hope" is a particularly rare commodity in cities that have been passed over for federal assistance again and again — even when federal agencies helped create those community's problems in the first place.

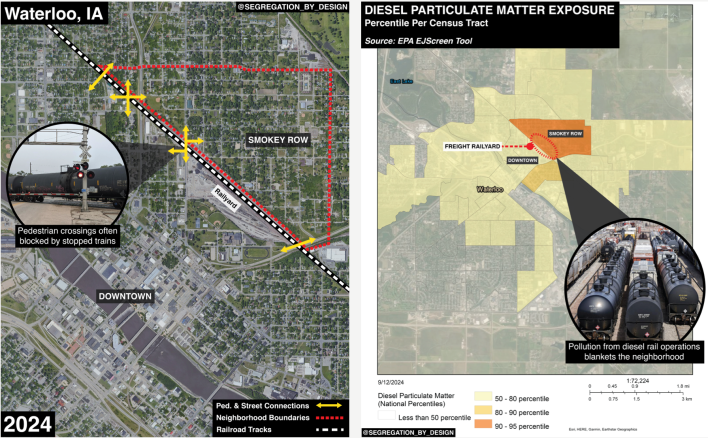

For Mayor Quentin Hart, for instance, life in his town of Waterloo, Iowa has been shaped by the presence of the Waterloo Railyard for as long as he can remember. The city's Black population has been heavily concentrated near the railyard for more than a century thanks to a long history of segregation and red-lining; today, rail remains a key industry for the region, even as the constant presence of diesel exhaust has ranked the area known as "Smoky Row" among the 99th percentile for asthma rates nationally.

Getting across those tracks, meanwhile, can often be a harrowing experience — especially for people traveling on foot. Freight traffic blocks the way for multiple hours every day, and more than one person has lost a limb while attempting to squeeze between two stopped cars that suddenly began moving again.

"I was born and raised in the city of Waterloo, and conversations about the railroad have been something that we've heard every day my entire life," Hart added. "[Projects like this] fit within our strategic goals, but they're also about making sure that you have the pulse of your community, that you're staying engaged."

That direct engagement with local priorities helped Waterloo win a $750,000 Neighborhood Access and Equity Grant to study the possibility of moving the railyard to the outskirts of town and redeveloping the land that's left behind in a way that better benefits Smoky Row residents. Hart credits the Infrastructure Hub especially with helping him galvanize his private partners at the railroad to join the conversation.

"The amount of federal support and federal dollars that are out there is empowering mayors to be able to shape age-old problems — challenges that government, unfortunately, has created in the first place," added Hart. "Organizations like Bloomberg Philanthropies and the Local Infrastructure Hub have really given us an opportunity to level the playing field and be able get dollars that we desperately need within our communities."

None of the Infrastructure Hub mayors are under any illusion that a one-time federal cash infusion will totally transform their transportation future — or, in Buffaloe's case, that even multiple grants can undo decades of auto-centric building. Even as she uses federal dollars to remediate the divisions caused by Business Loop 70, the state of Missouri is wielding far more federal money to widen nearly 200 miles of Interstate 70 — including a segment that runs through Columbia itself.

But that doesn't mean that she's is taking it lying down.

"[The Missouri Department of Transportation] says they're all about Vision Zero and doing pedestrian safety and multi-modal access, but we're not seeing it put into the infrastructure," Buffaloe added. "So we're having to do lots of strongly-worded letters, as well as putting the political pressure on, making sure that if they want something to pass, they're putting what we want in our community ... [I said,] 'Okay, well, while you're doing this, I would like you to add sidewalks. I would like you to add bike lanes to the roads that are crossing. I would like for you to add separated pedestrian crossings as you're looking at widening I-70 as it comes through my town.'"

Lavin says her group's next goal is to empower local communities not just to win infrastructure grants, but to effectively implement them in sometimes-hostile state political landscapes that are dividing new communities every day. And she also argues that giving mayors more direct infrastructure funding could help change that dynamic — and with the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law expiring soon, it's time to start the conversation now.

"What if these were recurring funds?" she added. "What if I didn't have to just plan for this one-time capital infusion, and I could actually rely on this in my budgeting? ... If we were able to give them that stable source of funding, so that they're not begging from their state for some of that formula funds, they could really take it to the next level.

"All these communities are asking for is: fix what you've done to us," she continued. "Make the funds available so that we can make the improvements to heal these communities and make them the vibrant places that they want to be."