Editor's note: this article is an excerpt from the Vision Zero Cities Journal and is republished with permission. For more information on the Vision Zero Cities 2024 conference, click here.

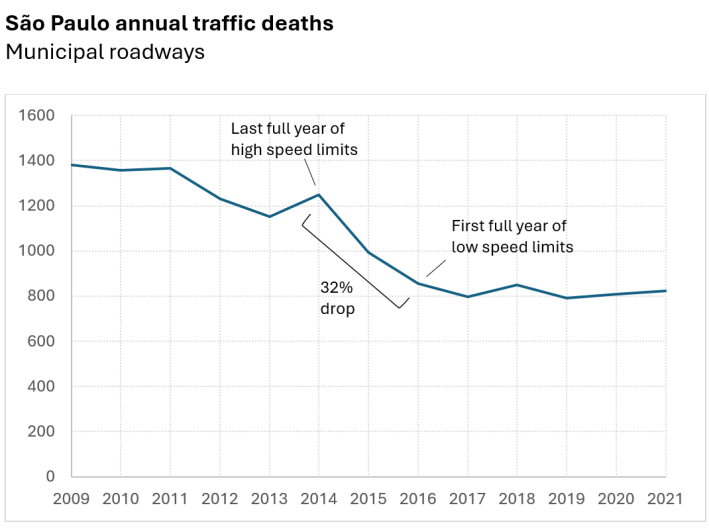

A decade ago, the largest city in the Americas suffered from 1,249 annual roadway deaths and 20 times as many injuries — a per capita rate of traffic violence twice as high as Los Angeles. In mid-2015, however, the death rate in São Paulo plummeted by a third and stayed down. To achieve this, the municipality simply cut speed limits, enforcing them with an existing system of cameras.

No city can expect zero traffic deaths if it lays out streets like raceways and treats people on foot as obstacles. That still largely describes São Paulo, which has four million cars circulating within city limits. It remains about nine hundred annual deaths away from the zero in Vision Zero.

However, with nearly 12 million residents today, the annual death rate sits at 7.5 per 100,000 people — down from 11.0 in 2014. Speed cameras have indeed helped São Paulo push its fatality rate to below that of Los Angeles, where cameras have been forbidden until recently by state law and fatalities have been rising.

Brazil overall is not known for careful driving. Its overall annual traffic death rate is 15.7 per 100,000 inhabitants, about 15% higher than in the US, which itself has the worst record by far among the world’s advanced economies. Brazil has only about half as many cars per capita as the US, so its fatality rate reveals a severe problem.

Behavioral change was visible after 1997 with a new national traffic code, which included camera enforcement and tightened drunk-driving rules. License points today accumulate easily to suspensions and mandatory re-training. By law, ticket proceeds go to signals, education, engineering, and enforcement, although there is not much public accountability on the specifics. The overall package — along with safer vehicle technology and rising educational levels — has produced a gradual decline in traffic lethality. The most dramatic changes, however, seem directly connected to camera enforcement, particularly of speeds.

On Brazilian highways, the accepted behavior is to slow at camera sites, which are marked, and then re-accelerate, often to 50% or more above the limits. That still saves lives, because camera sites concentrate at curves, crossings, and populated areas. In cities, there are enough cameras in some zones that many drivers give up trying to game the system. When enough drivers default to the limit, even those willing to take ticket risk tend to slow. Over time new habits form and the old speeds may feel too fast.

Drivers are especially aware of speed cameras in São Paulo because other cameras fine drivers in bus lanes, generate parking tickets, and restrict driving days. Tickets are assigned to the car owner unless another driver takes responsibility. Since even non-safety violations generate points, a single speeding ticket may tip the driver into suspension.

This system is why a simple change in legal limits in July 2015 caused actual driver speeds to drop overnight. Neighborhood maximums fell to 40 kph (25 mph) and 30 kph (19 mph) in school zones. Limits on most avenues were set at 50 kph (31 mph). The top speed on highways outside express lanes fell to 70 kph (44 mph). The tolerance margin is 10%, so while a New York driver in a 25-mph zone is ticketed only at 36 mph, a Brazilian driver would be ticketed at 27.6 mph.The safety impact was dramatic. On the deadliest highway in São Paulo, well-covered by cameras, fatal crashes fell 52% in the twelve months following the speed-limit changes compared to the preceding twelve. Across the whole city, deaths dropped 32% from 2014 to 2016, the first full year of the new speeds. The city estimated that 60 permanent public hospital beds were no longer needed for trauma incidents.

Speed cameras can of course generate equity concerns, but income distribution in Brazil is such that speed cameras tend to protect the walking, bus-riding majority from wealthier (and commercial) drivers. Enforcement in the US faces a different set of class, race, and policing issues, and about 92% of its households own a car, twice the Brazilian rate. Car dependency and poor transit in the US, compared to generally ample bus transit in Brazil, make license suspensions politically more sensitive. Fines are also generally flat fees in the US rather than tied to income as in some European jurisdictions.

Nevertheless, the personal financial impact of speed cameras is rarely heavy in the long run, because drivers learn. New York City, the most aggressive user of speed cameras in the US, has seen speeding drop nearly 75% at camera sites. Meanwhile, equity concerns about fines should be weighed against the inequitable distribution of crashes, which disproportionately affect those with low incomes, both in probability and financial impact. In a particularly dangerous traffic environment, São Paulo used automated enforcement to produce one of the world’s quickest and largest drops in crashes, saving thousands of lives and tens of thousands of people from hospital stays.

The Brazilian experience is an important example for the global Vision Zero movement, even if it can be uncomfortable whenever Vision Zero design-first concepts slide into design-only orthodoxy. The São Paulo data contradicts at scale the argument that speed cameras “don’t work” — and it’s a comparative case involving not compact pedestrianized European cities but a sprawling, car-oriented, new-world city.

What’s been disappointing in São Paulo is a lack of follow-through. As shown in the previous graph, the decline in the traffic death rate leveled off after the big drop when speed limits fell. The city and state governments have been investing heavily in transit infrastructure, sparing many people another chronic São Paulo traffic problem — congestion — but have not implemented substantial changes in street geometry, upgraded sidewalks, pedestrianized areas, or safe biking networks.

The world’s most advanced environments for safe streets, countries such as the Netherlands and Denmark, also use cameras to control speeds. But they understand that enforcement is only one tool in the kit, while more profound change requires redesigning cities overall to prioritize people over vehicle throughput. That requires a cultural shift and more public money than self-financed enforcement of speed limits, but it’s what Brazil needs to keep reducing the rate of traffic violence.