Editor's note: this article is an excerpt from the Vision Zero Cities Journal and is republished with permission. For more information on the Vision Zero Cities 2024 conference, click here.

Fifty years ago, in 1974, Curitiba inaugurated the first 20 kilometers of a pioneering transit system that, over the years, became known as Bus Rapid Transit (BRT). At that time, the city had about 600,000 residents (now nearing 1.8 million, with a metropolitan region of 3.8 million), and was one of the fastest-growing cities in Brazil. The innovative and cost-efficient public transit network helped mold and accommodate this growth, expanding from servicing 54,000 daily passengers in its first year to over 2.4 million by 2014.

Curitiba’s BRT system is elemental to the city’s identity, but has not escaped hardships: falling ridership numbers in recent years risked the health of the system, and it is only recent substantial efforts to upgrade both the fleet and infrastructure that have begun to reverse this negative trend.

In the five decades since its creation, Curitiba’s BRT system has inspired and served as a reference for cities worldwide, particularly the roughly 200 that have implemented similar models.

The creation of the BRT system is primarily credited to Jaime Lerner, who assumed his first term as Curitiba’s mayor in 1971. Resisting public pressure to widen arterial roads to accommodate growing traffic, he helped to conceive and refine the city’s master plan to preserve the structure of the city and took office with an acute understanding of how efficient public transit and urban development go hand-in-hand.

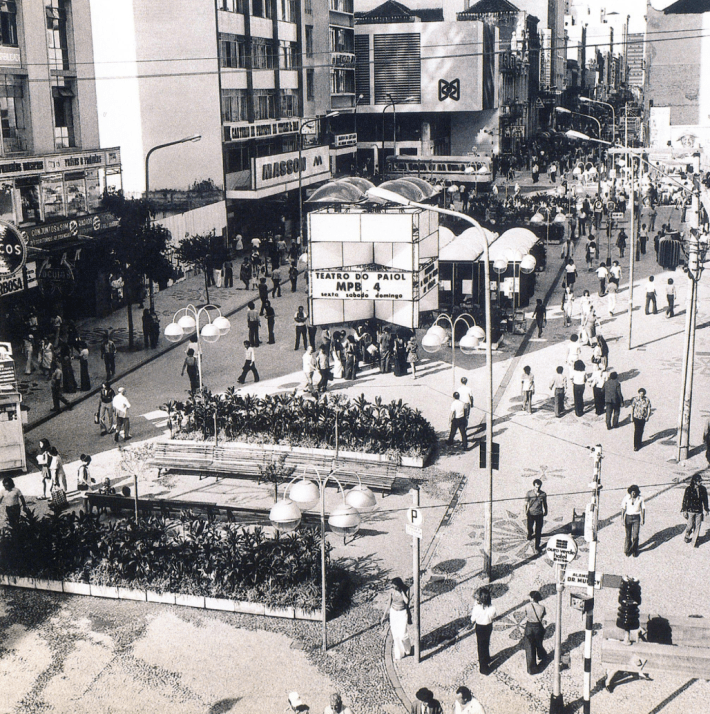

From the first days of his administration, the restructuring of the city’s transit system was guided by the underlying principles that cities are places of togetherness and thus need to be designed for people, not cars; that every city (particularly fast-growing ones) needs a clear structure to orient its sustainable growth; and that priority should be given to public transportation and pedestrians. These principles were not just rhetoric and were followed by the courageous implementation of Brazil’s first pedestrian mall in 1972 (Rua das Flores/Rua XV de Novembro), which closed the main commercial street downtown to cars despite fierce opposition, and the north-south transit axis in 1974.

Photo: Carros Antigos and Cid Estefani Archives

Urban design, transit infrastructure, and land-use laws are powerful tools in a planner and manager’s arsenal to guide urban growth. Transit lines built along major radial axes in the 1970s spurred development along these corridors before “transit-oriented development” became a buzzword.

By combining mixed land uses where the ground level was destined for retail and services, higher built densities, and a high-capacity public transit system with center-running bus lanes, the city created dozens of kilometers of BRT surrounded by dense and diverse land use. This decongested its downtown, decreased commuting times, and ensured high ridership to help balance the financial equation of the system’s operation by increasing passengers per kilometer traveled.

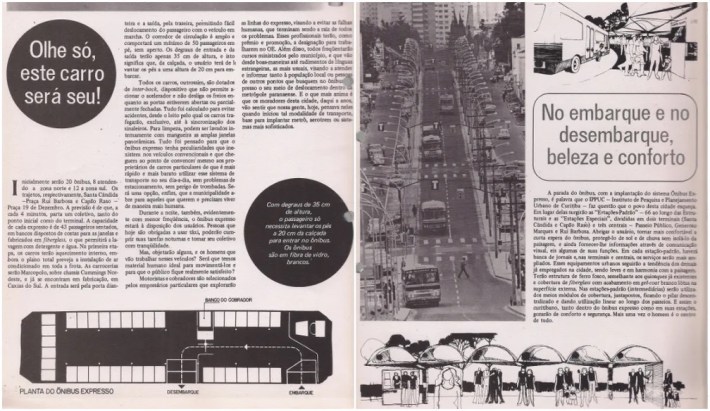

Though implementation was incremental, the new transit system of Curitiba was conceived as an integrated network. Instead of an ensemble of lines created or extended over the years to address existing demand, it was designed as a hierarchical system to address and organize current and future demand, guide growth (in conjunction with land-use policies), ease commuter life, and provide a clear identity, reliability, and high operational performance. A major innovation at the time was the reorganization of the existing lines into a “trunk-feeder” logic, where shorter feeder lines in neighborhoods converged at integration terminals along robust trunk lines running specially designed vehicles along dedicated busways, resulting in enhanced levels of service. Instead of having a jumble of overlapping lines that wasted time and energy, the trunk-feeder solution improved travel times and user experience.

From the initial 20 km of dedicated busways, it expanded to 80 km, with 34 integration terminals and over 350 tube-stations. With this expansion came a steady growth in ridership: in 1974, the network carried about 54,000 passengers each day. At the height of the network integration in 2014, it carried almost 2.5 million passengers each day in Curitiba and other 13 integrated metropolitan municipalities.

Simplicity, creativity, flexibility, expediency, and affordability were guiding tenets. Curitiba, like most cities, could afford neither the construction nor the long-term fare subsidies of an underground subway.

A bus-based surface system can be adapted to the existing infrastructure of virtually any city; it has the flexibility to mold or alter itineraries according to planning and/or demand; and it can be implemented more quickly, compared with rail systems, for a fraction of the cost. These tenets are also strikingly identifiable in subsequent features that defined Curitiba’s BRT, such as the ground-breaking concept of the “tube stations,” which incorporated the subway-defining elements of pre-paid and same-level boarding into a surface system.

To win over skeptical Curitibanos, who were used to slow, unpleasant, and inefficient bus service, the city invested in a strong communication campaign, and a “lead by example” strategy, with Lerner engaging directly with the population. The city committed to encouraging bus travel through a new visual identity, specially designed bus stops and vehicles, and technological innovations. Jaime Lerner wanted the public transit system to be an accepted option even for those who could afford a car, not just for those who could not.

The integrated transit network of Curitiba has served its people well and has become a core element of the city’s identity. Expansions and updates over the years have aimed at keeping the network updated and in tune with the city’s development guidelines. At the turn of the millennium, a new corridor was created in the southern part of the city along a former federal highway to become a new “structural sector” at the metropolitan scale.

While the original corridors were designed with a single bus lane in each direction, since the mid-2010s they are progressively being redesigned to allow overtaking, enabling simultaneous direct and stopping lines, and significantly increasing their capacity. For over ten years now, vehicles have been incorporating new technologies, such as hybrid engines running on biodiesel, and electric mobility is advancing, with the first 70 electric buses having recently been incorporated into the fleet (aiming at 30% of the fleet by 2030 and 100% by 2050). Upgrades to electronic ticketing offer more flexible integration, allowing for line exchanges not only inside the bus terminals and tube stations but also to lines that are not connected to these junctures. Circular lines (interbairros) are being upgraded with dedicated lanes and specially designed, climate-controlled stops that include multi-modal facilities and new communication technology.

There have also been many challenges. Metropolitan integration is subject to the political priorities of different state and municipal governments and, since 2015, the 13 neighboring municipalities have split their transit systems off from Curitiba’s transit network Long-term federal policies that subsidize the acquisition of “affordable cars” and motorcycles, the separation of the metropolitan operation, the COVID-19 pandemic, and ride-share innovations like Uber have led to substantial ridership losses. This results in decreased revenues which, added to factors such as extreme inflation’s effect on operational costs (the cost of diesel doubled between 2021 and 2022 alone), puts pressure on the fares and compromises investment in improving the quality of the system. Higher fares and a worse rider experience lead to more losses in ridership, creating a vicious cycle.

The network reached its low point in 2020, dropping to a little over 710,000 passengers transported per day. Fortunately, numbers are recovering and were up to 1.1 million in 2022. Recent years have seen substantial efforts to regain quality, improve service levels, incorporate technical innovations, and initiate more robust projects to reinvigorate the integrated transit network, thus honoring this precious multi-generational heritage of the people of Curitiba.

In loving memory of Jaime Lerner (1937–2021), Carlos Eduardo Ceneviva (1937–2020), and Rafael Dely (1940–2007), masterminds of the incredible innovation materialized in the Integrated Transit Network of Curitiba (the “BRT”) and the structural sector design.