This piece originally appeared on How Things Work with a slightly different headline and is reprinted with permission.

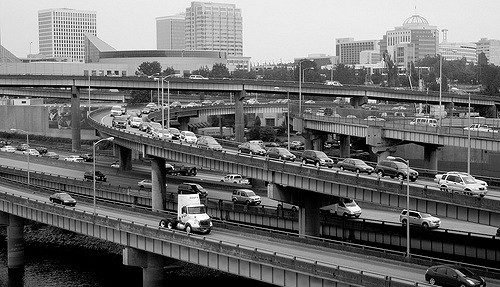

There is much beauty in America. Yet, on average, America is an ugly country. The median American scene, the one that illustrates the most typical view of the most typical place, would be an exhaust-choked roadway flanked on both sides by fast food restaurants and big box stores. This is what we have done with our purple mountains, majesty, from sea to shining sea.

The culprit is the car. More specifically, the culprit is America’s decision to design our cities around the car. Predicting the future is almost impossible, but one of the few predictions that I feel very confident in is that, a century or so down the road, people will look at modern car-centric America with the same disgust that we feel when we hear about old timey cities without modern sewage systems, where everyone just dumped their chamber pots in the street. “Whoa, that’s fucked up!” people will marvel from their quiet, pedestrianized cities of the future. “They couldn’t walk anywhere.”

America’s collective decision in the 20th century to make cars and the roads serving them the bedrock of all urban and regional planning will go down in history as just another of our nation’s awful, ruinous ideas that we nevertheless clung to for generations, like slavery or lead paint. Cars, of course, have a way of making themselves very hard to progress away from. Once you build the towns and cities around the road patterns for cars, and allow the interstate highway system to determine development patterns, the entire system gets locked in in a way that is difficult to change. Even as ever-widening highways and air pollution and the immense parking lots destroy ever larger swaths of peace and scenery, they also represent ever larger sunk costs from consumers and governments, which make everyone more reluctant to try to break away from them.

New cars spawn new roads. New roads spawn new sprawl. It all spawns new debts. To admit that this entire thing was a mistake involves surveying our suburban homes, our paved driveways, our SUVs, our shopping centers, our entire beloved home towns, and saying: Okay, this has all gotten out of control. As all addicts know, this piercing self-criticism can be more difficult than just continuing doing something that is unhealthy, but familiar.

Tennessee Williams famously said “America has only three cities: New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. Everywhere else is Cleveland.” I might toss in Chicago and Philly, but the observation still holds true today—except that now, everywhere else is Denton, Texas, or The Shitty Sprawl Outside of Tampa. It is no coincidence that the real cities in America are those that developed enough before the rise of cars that they could not be totally destroyed by the Highway Cloverleaf Era. Robert Moses did his best to fuck up NYC, and New Orleans got I-10 bulldozed straight through it, but both had enough urban character already in place to survive. Not so for most places. Americans unlucky enough to grow up in more recently built towns and exurbs are stuck having their entire lives defined by the spatial needs of cars. Their neighborhood density is low, their mobility options are limited, and the most urban-esque experience they ever get growing up might be playing with friends on the pavement of a suburban cul-de-sac. Never will they “walk” to a “corner store.” Always will they drive to a Target. If there were ever any beautiful nature along the way, now there is only highway and billboards and shredded semi truck tires on the side of the road. Sad.

Since Jane Jacobs, urbanists and regular city residents alike have had the strong intuition that building more roads to fit more cars into cities is a fundamentally stupid thing. Engineers have long known that widening highways does not fixtraffic gridlock, but that has not stopped states from spending billions of dollars to build more and more lanes, until huge swaths of LA and Houston and Atlanta resemble dystopican concrete car rivers more than cities where humans might live. A new study in the Journal of the American Planning Association provides the best estimate yet of just how much space we have ceded to roads in our cities. “ We found that a little less than a quarter of urbanized land—roughly the size of West Virginia—was dedicated to roadway. This land was worth around $4.1 trillion in 2016 and had an annualized value that was higher than the total variable costs of the trucking sector and the total annual federal, state, and local expenditures on roadways,” the study found. In an example of the sort of dry wit that you might not expect from the Journal of the American Planning Association, the authors added, “Conducting a back-of-the-envelope cost–benefit analysis, we found that the country likely has too much land dedicated to urban roads.”

In fact, the study calculates that “the average cost of expanding roadways exceeded the benefits by a factor of nearly three when accounting for land value.” This observation gets to the heart of the most common-sense objection to the way that we allow roads to dictate urban development: the more space that we dedicate to getting there, the less space there is for where you are trying to get. To see a city choked by busy roads is to witness a manifestation of missing the point. Roads are barren, inhospitable landscapes whose only redeeming value is allowing us to reach somewhere much more pleasant than the road itself. When roads come to dominate the non-road area of a city, you have, by definition, built too much road. It is like building a staircase that takes up the entire first floor of a two-story house. You have left yourself nowhere to live.

This grotesque pattern of development rests upon a wild overvaluation of “how long it takes to drive somewhere” and an accompanying undervaluation of “all quality of life categories apart from driving time.” Unfortunately, the path out of our predicament is a long one. Ripping ill-advised existing highways out of citiesis a great idea, but it will be most helpful only in cities that were well developed before the highway existed. The situation of the millions of Americans who live in newer sprawl-based towns and suburbs whose entire design is based on the idea that you will drive anywhere any time you want to do anything is more grim. These are the places where the handful of impoverished car-less citizens are forced to pedal bikes on the unprotected shoulders of roads like suicidal hobos. To suggest that these places should stop being car-centric is to suggest that they should probably just be bulldozed down to the dirt and rebuilt as civilized compact urban areas suitable for mass transit. I don’t expect that will happen any time soon. But it wouldn’t be a bad idea.

Instead, I expect that America will undergo a long process, lasting much longer than my own lifetime, in which cities that are not built around cars will gradually expand and attract an ever-increasing share of the population, and the most thinly populated car-centric places will gradually decline in value, because they are just not nice places to live. Medium sized cities in places like the Sunbelt that experience a lot of growth due to affordable housing prices or economic booms will, at some point, reach levels of density that make car-centric planning so clearly insane that even the most truck-loving state and local governments will be dragged into the age of mass transit, by necessity. This is one of those areas where you can be pretty certain that a better future will arrive purely because the logic of it is unavoidable. And you can be equally certain that the path to getting there will be longer and more excruciating than it should be, because here in America, we will stubbornly cling to our outmoded, counterproductive, discredited ideas longer than anyone.

We’re number one!