When state transportation agencies widen a highway, they tend to put out a buzzy press release about all the exciting new "improvements" that are coming to the road, without any mention of how disastrous that "upgrade" will really be for the climate, safety, and equity in our communities. Some of the language they use, though, can be surprisingly hard to spot – unless you're an advocate in the know.

Inspired by the incredible advocates at the Freeway Fighters Network, here's a cheatsheet of eight common arguments, distortions, and outright lies that transportation officials use to sell the public on widening streets and roads — and how to debunk them.

Think we missed one? Email kea@streetsblog.org to let us know.

1. 'We have to widen this road to fight congestion'

Let's start with the granddaddy of all highway-widening myths: that creating more space for cars will give everyone a little more room to speed up, curing traffic jams even as the local driving population grows. And since pretty much every traffic model assumes that local populations will explode, pretty much every road could benefit from a little more "capacity," or extra lanes.

Multiple freeway fighters shouted out David Zipper's excellent recent explainer in Vox about why this is nonsense, even if it seems true at first blush:

"These projections have a fatal blind spot: They fail to consider how humans respond to changing conditions like new vehicle lanes," Zipper wrote. "When people see cars traveling freely over a recently expanded highway [or other road], they will recalibrate their travel decisions. Some will choose to drive at rush hour when they would have otherwise driven at a non-peak time, taken public transit, or perhaps not traveled at all.

"Such behavioral adjustments will continue until traffic is as thick as it was before, when the roadway was narrower," Zipper continued. "The only difference is now there will be more cars stuck in traffic, emitting even more pollution."

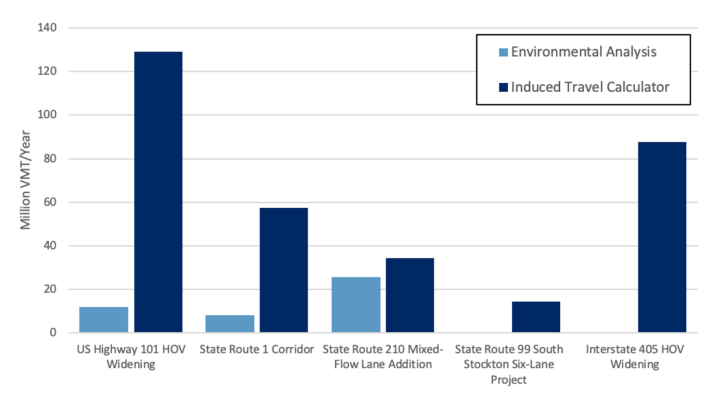

That phenomenon, known as "induced demand," was documented as early as the 1920s and countless times since; one recent research round up from UC Davis found that for "every 10 percent increase in highway capacity, vehicle miles traveled will increase by close to 10 percent within five to 10 years." But engineers are still ignoring this basic principle in their traffic projection models to this day, and federal guidelines still don't require them to include it to get federal money.

Other advocates pointed out that engineers are also ignoring the power of reduced demand, one meaning of which is how many fewer people will walk, bike and take transit when a nearby road is widened. Multiple freeway fighters pointed out that traffic engineers rarely even bother to count pedestrians, cyclists, and transit users on nearby roads, much less factor in how many of them climb into cars or simply stay home when a mega-highway is razed through their neighborhood.

"By not counting other modes, they make them invisible," wrote Andy Kunz, president and CEO of the U.S. High Speed Rail association. "If we saw actual numbers of how many people get around by bicycle, walking, and rail, the results would greatly favor moving substantial funds away from roads into those other modes."

2. 'We have to widen this road to fight climate change'

If ignoring the phenomenon of induced demand is the granddaddy of all climate widening tricks, claiming that road widenings reduce emissions is its toxic grandson.

The (flawed) reasoning behind this myth is, basically, that when cars are stuck idling in traffic jams for hours and hours, they'll release more emissions than if drivers are traveling swiftly to their destinations — so we better hurry up and add some lanes to speed them up.

Even if induced demand didn't exist, though, this argument wouldn't necessarily make sense, because cars emit more pollution the faster they're going. In a highway context, especially, super-high speeds can easily overwhelm any emissions that are saved by building more lanes to eliminate traffic jams — and because induced demand does exist, all those traffic jams will just come roaring back within five to ten years anyway.

Moreover, about 65 percent of new cars now come equipped with stop-start technology that eliminates engine idling completely, and an increasing percentage of cars are fully electric. Highway agencies, though, are likely to cling to the myth that "reducing idling" is their number one priority as long as they can — and they'll keep widening highways to do it. (As our Streetsblog NYC colleagues pointed out this week, it's even happening in climate-aware New York City.)

3. 'We're just leaving some extra space for a future transit line'

When transportation officials can't sell a road widening on its supposed climate benefits, they'll often claim that their ultra-wide road could double as a transit corridor ... someday, theoretically, hypothetically, "if funds allow."

Kunz pointed to the Wilson Bridge project in the Washington, D.C. area, which was "constantly sold as having space for a future metro line — and here we are many years later... no Metro, and the bridge full of vehicle lanes. It's a bait-and-switch technique they use all the time."

Out in Portland, City Observatory author Joe Cortright has extensively documented the state Department of Transportation's attempt to convince the public that they're only widening Interstate 5 to run "bus-on-shoulder" service ... on a route that currently has no bus service, with a transit agency that rarely runs buses on interstate shoulders at all.

Journalists at the Williamette Week compared the move to "buying a birthday saddle for a kid who doesn't own a pony" — and Cortight says it will be all too easy for the agency to revise their plans once the highway is inevitably clogged with cars, and transportation officials claim they "need" the extra space to accommodate them.

"Once built, the DOT can use the USDOT categorical exception for projects entirely within the right of way to widen the road without further environmental review," he wrote.

Unless transportation officials are making an ironclad commitment to adding transit to the corridor, complete with real funding and a promise not to add capacity for drivers, it's best to assume that their transit promises are empty — and even if they aren't, it's wise to question why they need to widen the road to do it, rather than reducing capacity for drivers.

4. 'We're just adding 'auxiliary lanes' to make the road safer'

One of the more technical terms that gets thrown around during debates over highway widenings is "auxiliary lanes," which are basically short sections of lane between highway on-ramps and off-ramps that drivers can use to gain or reduce their speed as they merge into and out of faster traffic in the through lane. DOTs argue that auxiliary relieve congestion and make roads safer at once.

The trouble is, those "short" sections of extra lane often aren't really that short at all, and they end up functioning as exactly what they are: an extra highway lane that just encourages more people to drive and increases more congestion over time, just like any other extra highway lane. Some DOTs own assessments of their projects, like this one in California, have found they don't improve safety, either.

The Oregon Department of Transportation has also leaned hard on the need for "auxiliary lanes" in its proposal to widen the Rose Quarter freeway and dump pollution on a nearby majority-BIPOC middle school to do it.

"ODOT's official designation for the Rose Quarter expansion projects is 'safety and operations.' It's actually the addition of 1.8 lane-miles of freeway in the heart of Portland," said Chris Smith, a Portland based citizen activist. "Anything that reduces friction for traffic to flow is going to induce more demand, a fact that ODOT goes out of their way to minimize or deny."

Other advocates argue that even more limited "auxiliary lane" projects should be treated with suspicion.

"We're [told that] only increasing the length of entrance and exit ramps," said Dennis Grzezinski, a Milwaukee-based environmental lawyer who's worked on freeway fighting projects. "But the increase adds a full lane between one entrance and the next exit, and only re-striping is needed to convert the 'auxiliary lane' into a continuous travel lane."

Others had an even pithier retort.

"[So you're building] 'auxiliary lanes' instead of 'widening'," said David Bragdon, the former head of Transit Center now with Hudson Skykomish. "Great; will those lanes only emit auxiliary carbon?"

5. 'Don't worry; it's a carpool lane!'

Adding a "high occupancy vehicle lane" or "carpool lane" might sound like a great way to encourage drivers to fill up every seat for a more efficient ride. In practice, though, these lanes often just induce more demand — or they sit empty.

As the authors of a great 2022 Reason explainer once wrote, "As many as three-quarters of people using HOV lanes legally are either family members traveling together (fam-pools) or a parent driving kids to school (school pools), but neither situation removes vehicles from the roadways in the way that carpool lanes were intended to remove cars."

In the rare situation where a few co-workers do manage to coordinate their schedules and pile into the same SUV, they might find themselves stuck in a traffic jam with a bunch of solo drivers in the carpool lane anyway — because carpool lanes are notoriously expensive and difficult to enforce. One 2018 study found that "84 percent of the vehicles in Tennessee’s HOV lanes were violators."

And even when states do figure out how to keep single-occupancy vehicles out of the shared lane, it might not matter much, because car-pooling gets less and less feasible the more car-dependent America gets. "Between 1995 and 2005, HOV lane miles doubled from 1,500 to 3,000 lane miles, but carpooling plummeted from 19.7 percent of commuters in 1980 to only 8.9 percent in 2019," Reason said.

6. 'Don't worry; we're adding a freeway cap!'

One common highway con that's in serious vogue right now is the idea that transportation officials can erase the harm of widening a deadly road by building a "cap," "stitch," "land bridge," "lid," or "deck plaza" over part of it, opening up new opportunities for developments, parks, or even safe walking and rolling on top.

There's nothing inherently wrong with turning highways into de-facto tunnels on its own — at least when there's truly no political will to turn them into boulevards. But freeway fighters say building a land bridge over a deadly road while actively widening that road beneath it is a little like deliberately gouging open an unhealed wound to make it even bigger, and then putting a Band-Aid over it.

In Austin, for instance, TxDOT is planning on widening I-35 up to 22 lanes in some sections — and advocates say that the series of highway caps that will be placed over top won't significantly mitigate all the added emissions and congestion that humongous road will induce.

Moreover, the city of Austin itself will have to find the money for their own caps, in addition to the more than $6 billion that Texas taxpayers are spending on the senseless highway expansion they're meant to cover— and if they want the decks to be strong enough to support the weight of buildings rather than just grass, it could cost even more.

"To cover small isolated sections of the expanded I-35 with 'caps,' TxDOT is forcing Austin to raise more than $800 million, making taxpayers cover up TxDOT’s mess," wrote Susan Pantell, an Austin-based transit, environment and affordability advocate. "The $800 million is probably an underestimate. ... The city is so strapped for funding with so many needs like addressing homelessness and climate change weather impacts; we don't have that kind of extra money."

Despite all this, the I-35 cap-and-stitch project scored a $1.12-million planning grant from the federal government's "Reconnecting Communities" last year, as did several other land bridges and decks over soon-to-be-widened highways.

7. 'Don't worry; we're adding some biking, walking, and accessibility improvements, too!'

Another simple way to greenwash a road-widening is to build some nominal improvements alongside or across that road for people who walk, bike and roll... all while simultaneously creating a route where no one in their right mind would ever want to travel outside a car.

Whether it's a pedestrian bridge where walkers are blasted with highway smog from below or some lights and zebra markings on a newly-widened stroad that's now twice as terrifying to cross, many DOTs will brag about a handful of "enhancements" for non-drivers in these projects— even as they unleash a flood of car traffic on nearby roads that didn't get those upgrades.

"[Agencies will say] this project helps pedestrians and bicycles because we added this crosswalk/pedestrian overpass/better traffic signal," said Ben Varick of the Wisconsin Bike Federation. "While also increasing speed and volume of car traffic exiting the highway onto local roads that have lots of pedestrians."

Even great active transportation infrastructure on a newly-widened road might not mean much if it doesn't connect to a network of other great infrastructure.

"Throwing a bus lane or perhaps a bike lane from nowhere to nowhere along a highway — [while] continuing to fail to build out missing comprehensive and safe networks — is an ongoing problem," said advocate Marie Venner.

Perhaps the worst shade of lipstick DOTs can put on a road-widening pig, though, is when they brag that these projects will usher in a mess of new accessibility improvements for people with disabilities ... without mentioning that those "improvements" are actually required by federal laws that they've been violating for decades.

Worse, by pouring money into road expansions (albeit with a sprinkle of ADA work on the side), transportation officials are actively diverting money that could be spent making the rest of their city accessible to all residents, and using it to make one road more convenient for drivers. And because of induced demand, it doesn't even work long term.

"Curb ramps, accessible crosswalk signals, and other aspects of infrastructure are neither improvements nor enhancements; they are federal legal civil rights mandates," explained North Carolina-based advocate Steven Hardy-Braz, who uses a wheelchair himself. "How can they justify spending more money on some widening project when they are already in violation of federal legal mandates and depriving people with disabilities of their civil rights to access?"

8. 'We have to widen the highway, because we already spent the money to study it'

When all other road-widening ruses fail, DOTs can always point to any bureaucrat's best friend: good old sunk cost fallacy.

"[One] trick pioneered by Robert Moses [was] spending $100,000 for 'planning and engineering,' and then coming back to the board and saying, 'You have to give me $100 gazillion now, because we have already committed so much money to planning and you don't want it to go to waste,'" added Bragdon. "Someone [once] observed that there are two phases of public involvement on a highway project: the phase where it is too early for the public to comment or the agency to respond because nothing has been decided yet, followed by the phase where it is too late for the public to comment because these things have already been decided."

The truth is, it's never too late to stop a road-widening project — even if the massive machine of the car-dependency lobby makes that prospect seriously daunting. And freeway fighters all over the country argue that with our planet, our safety, and mobility justice itself on the line, we simply can't afford not to fight back.