The Covid pandemic alone doesn't explain the surge in pedestrian deaths during quarantine, a new study finds — and to curb the carnage, America will need to get serious about addressing the root causes of traffic violence that long predated the deadly virus.

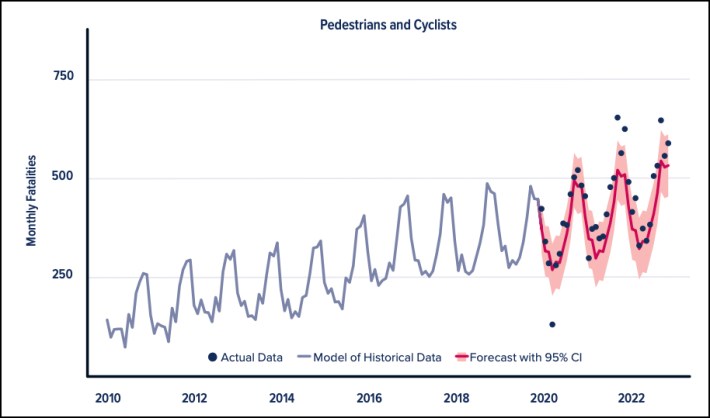

The number of U.S. walkers who were killed by drivers between 2020 and 2022 was actually not significantly higher than researchers would have anticipated had COVID-19 never broken out, according to a recent study from the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety. But that's only because pre-pandemic models were already predicting a series of record years for pedestrian deaths, since they'd been trained on more than a decade of increasingly deadly data — and that prediction unfortunately, came true.

"We've been seeing pedestrian fatalities increase year after year since their record low in 2009 — record low being, of course, more than 4,000 people," said Brian Tefft, the Foundation's principal researcher. "The increasing trend of pedestrian fatalities had already lead us to expect [more and more deaths] — and that's exactly what we got."

Of course, pedestrians weren't the only ones who experienced a roadway death surge — and for many groups, those increases were much bigger than anticipated.

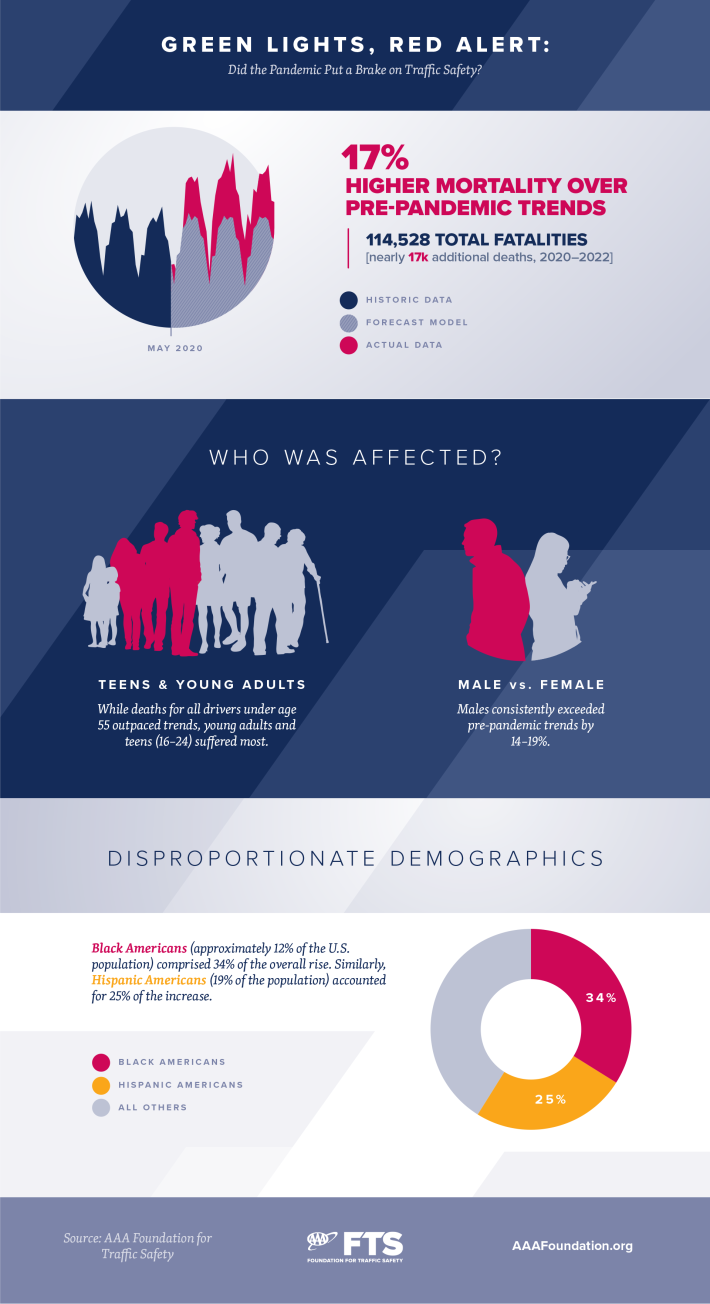

The researchers found that young adults between 16 and 24 reported the largest unexpected bump of all, followed by men, people with less education, and drivers without valid licenses. Black and Hispanic road users, meanwhile, vastly exceeded projections, too, accounting for 34 and 25 percent of the overall death total increase, respectively, despite making up just 12 and 19 percent of the overall population.

All of those groups, of course, were statistically over-represented among road death totals before the pandemic, too — but the onset of COVID-19 amplified those horrifying disparities even more. And Tefft says that's an unfortunately common trend outside the traffic safety realm, too.

"We know that the impact of the pandemic was vastly unequal across our society, both in terms of the COVID-19 virus itself as well as the impact of all of the social changes that took place after the pandemic," he adds. "Things like working from home became relatively more common, at least for people who could do that. ... And when we're seeing those kinds of changes, that demand is being met by people who aren't able to work from home and order their dinner from their sofa. They're out there doing the work and carrying the weight of society on their shoulders — and they're still exposing themselves to risk on the road."

The million dollar question, of course, is why the pandemic amplified roadway death disparities among so many groups — and why our already-stunning pedestrian death total wasn't even higher than it was.

Contrary to one popular hypothesis, the researchers say the overall increase likely wasn't exclusively attributable to a national drop in motor vehicle traffic, which some experts theorized allowed the remaining drivers to speed on empty roads.

Yes, deaths did increase during what used to be the rush hour, but "the largest increases in traffic fatalities occurred during the late night and early morning hours — times during which speeding generally would not have been precluded by congestion even before the pandemic." Moreover, death rates stayed high even when congestion levels returned roughly to normal in 2021.

The more likely — if less satisfying — explanation, Tefft said, was a sharp increase in "aberrant driving behaviors" like speeding regardless of who else was on the road, alcohol-impaired driving, and driving without a license. Among vehicle occupants, the increase was experienced "almost entirely among occupants not wearing seatbelts."

A 2022 study from the Foundation found that the riskiest drivers on the road actually drove more during the early days of the pandemic, even as most U.S. residents' mileage declined. And some research suggests those behaviors may have gotten worse as the pressures of the pandemic grew.

"We know that there's significant research by others showing that all sorts of factors that became especially acute during the pandemic — things like stress, anxiety, depression — really do impact people's driving and just how safely they drive," Tefft added. "So it stands to reason that a lot of people who were most at risk just because of the demands life was placing on them during the pandemic might have been experiencing more risk behind the wheel as well."

Tefft stressed, though, that we can't blame the roadway death crisis on a few bad-apple drivers cracking under pandemic-era stress — especially when systemic solutions exist to save lives even when motorists are driving like maniacs.

Impaired driving prevention technology, speed limiters on cars, and speed-reducing road designs could all have curbed the bloodshed during the early days of COVID-19 — just like they could have saved lives before the pandemic and since. And deploying them equitably in the most vulnerable communities remains as essential now as it's ever been.

"We need to double down on the safe system approach, and acknowledge that humans, despite their best efforts, aren't perfect," Tefft added. "A few [people] might behave in ways that we'd prefer they wouldn't, but we can and should find ways to engineer the risk out of the system. When people make mistakes — [which] we know they're inevitably going to make — we don't want the system to set them up to be killed, or to kill somebody else."