Watch it burn.

America cannot meet its goals to decarbonize the transportation sector by switching to electric vehicles without reducing how much Americans drive, according to a new U.S. Department of Transportation report sent up to Congress — but it's unclear if any level of government is prepared to take the steps necessary to do both.

Earlier this month, US DOT published a congressionally-mandated progress report on the department's own efforts to reduce our national transportation sector emissions, which has been the country's leading driver of climate change since transport surpassed the electricity sector in 2017.

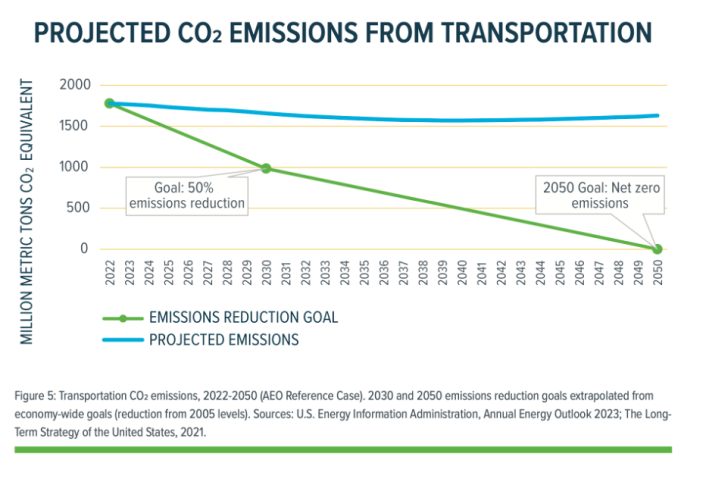

The short answer is: it's not going great. Assuming that no further climate legislation is passed, one study cited in the report found that transport emissions are on track to grow a staggering 23 percent by 2050, rather than falling to net zero, which experts say is necessary to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

The Biden Administration's signature climate bill, the Inflation Reduction Act, will bend the curve slightly "as a result of fuel economy improvements and greater deployment of electric vehicles," the same analysis found — but that decline will be quickly erased "due to increasing vehicle miles traveled for both passengers and freight," the report authors wrote.

The report makes it clear that DOT isn't the only agency that will be blamed if we can't clean up our transportation system — Congress, state highway offices, and local leaders all need to take a hard look in the mirror if they want to prevent the worst.

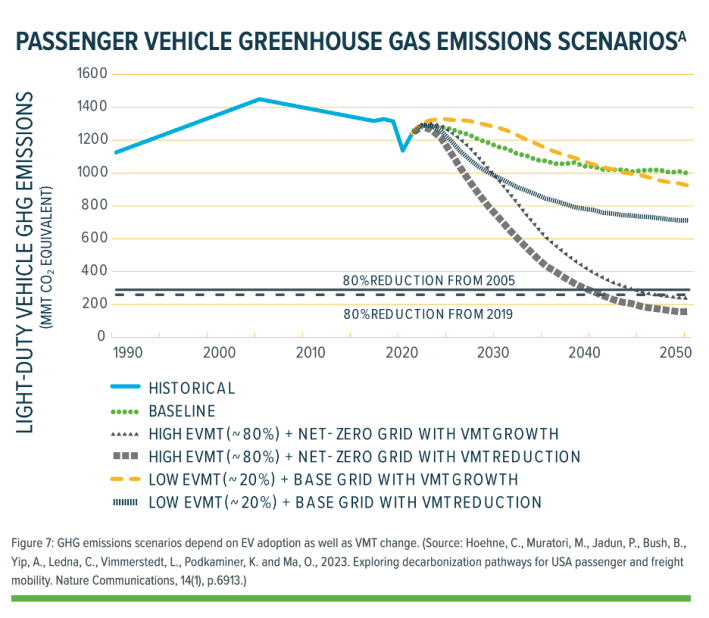

That's in large part, the report suggests, because no level of government has been aggressive enough about reducing how much Americans drive. One recent study cited in the paper found that the only path to meaningful emissions reduction that still allowed for VMT growth required both 80 percent of the vehicle fleet to be electrified by 2050, and the total decarbonization of the electrical grid — and even then, it just barely squeaked in under the line. Meanwhile, experts estimate that only 30 percent of cars will have batteries by midcentury.

Or, as the report authors put it bluntly: "The U.S. will not be able to decarbonize the transportation sector by midcentury without addressing increased demand."

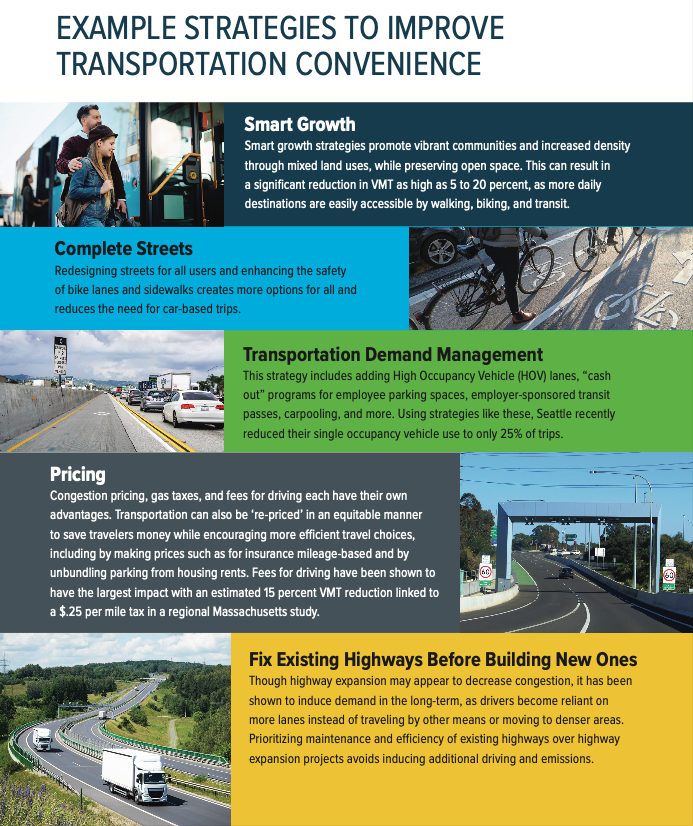

That harsh reality was also underscored in more subtle ways throughout the report, which routinely placed policies that support biking, walking, transit, and other non-automotive modes at the top of its various lists of decarbonization strategies.

Specifically, DOT says the agency and all of its partners in government will need to "increase convenience" by decreasing the distance Americans need to travel to key destinations (and the safety they can expect along the journey), as well as "improving efficiency" by supporting mass transportation and better freight strategies.

"Increasing clean options" like electric vehicles was the third item on its list.

The question, of course, is why America remains so devastatingly car-dominated if DOT knows that our current level of driving is unsustainable — and what it will take to change course.

Of course, no small part of that has to do with Congress itself, which passed a deeply flawed Bipartisan Infrastructure Law that doled out billions of largely unrestricted dollars that states and metropolitan regions are using to build highway expansions, rather than repair the roads they've already got or make them more welcoming to non-drivers.

Part of it has to do with state leaders who mount massive lawsuits against US DOT for simply asking them track their transport-related emissions, never mind reduce them, all while defunding transit to build deadly highways and stroads through local communities that only make pollution worse.

Some has to do with local leaders who have resisted the kind of zoning reforms and street-level safety measures that would make walking or biking simply possible, much less an attractive way to get around.

And yes: some has to do with DOT itself, which despite everything it said in this report, has still granted discretionary grants to projects that would expand highways, even as it purports to "reconnect" the communities around them with nominal freeway caps.

This is far from an exhaustive list of all the ways that American policymakers have gotten the transportation sector into this mess, and a 66 page report won't be enough get them out of it. Now that the basic facts are out on the table, though, the message is clear: our species will not survive if we do not take bold action to reduce car dependency, and the time to start is yesterday.