The U.S. is experiencing a historic surge in micromobility trips — but without more public subsidy, that boom could easily go a bust, a new report argues.

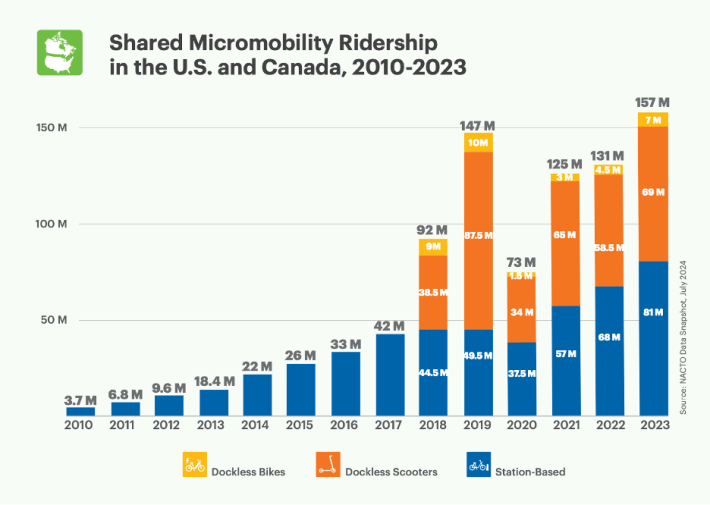

North America set a new record for the most shared bike and scooter trips in a single year in 2023, soaring 20 percent compared to 2022 and exceeding even pre-pandemic numbers. And that increase happened on both sides of the border, with Canadian cities reporting a whopping 40 percent increase and the U.S. reporting 16.

But according to the National Association of City Transportation Officials, which compiled the numbers, that increase happened in spite of a fragile micromobility ecosystem in which even popular programs have suddenly shut down. Riders, meanwhile, could soon find themselves struggling to pay higher fares on the bikes and scooters that remain, with annual pass costs rising 20 to 30 percent in some of the largest programs on the continent.

“Shared micromobility is at an inflection point," wrote NACTO. "It is imperative that cities design durable operational models to ensure the long-term viability of this increasingly relied-on transportation mode."

The NACTO report stressed that there's no one reason America's micromobility future is so vulnerable, even as more Americans than ever clamber for ways to get around without a car. "Mass layoffs across multiple private operators" like scooter giant Bird caused many U.S. cities to lose access to shared options "overnight" in 2023, but even publicly financed systems in Cincinnati, Houston and Minneapolis proved equally vulnerable when major sponsors suddenly pulled out.

Fare increases, meanwhile, may soon result in ridership losses, which will definitely affect providers, especially as expensive-to-service e-bikes continue to explode in popularity and dominate a larger share of fleets. In Los Angeles, for instance, pedal-assist vehicles proved eight times more popular than their bio-bike equivalents in 2023, despite the fact that most providers add on an per-minute surcharge, bringing the total cost to ride up well above the typical bus or train fare.

Many companies have tried to soften the blow by offering discounts to riders living at the lowest income levels. NACTO argues, though, that this approach "does not address the growing cost-of-living crisis squeezing the working and middle class in cities across North America," and that cities should "consider ways to make their shared micromobility systems more affordable for every rider."

In practice, the report authors argue, that means cities must "begin subsidizing shared micromobility like the public asset it is" — and to do so in multiple ways.

In some communities, NACTO sas that could mean outright public ownership of micromobility programs and direct taxpayer subsidies to bring fare costs down across the board, just like drivers and transit users broadly enjoy, albeit to very different results. In others, it could mean eliminating sales tax on rides, similar to the break other transit users get at the farebox. Or it could mean simply building a lot more protected bike lanes to encourage higher ridership — which some research shows great infrastructure does — and deliver providers both a stable fare base and a cushion to drop prices over time.

However cities choose to do it, though, NACTO says they shouldn't count on the micromobility revolution to keep rolling without some help from taxpayers — and considering the massive societal benefits of giving people affordable, accessible alternatives to compulsory driving, that's an investment well worth making.

"Now is the moment to fully consider whether shared micromobility serves as public transportation, or primarily as a downtown economic development tool," the group wrote. "For cities that wish to provide shared micromobility as a public service, a hard look at finances, subsidies, and affordability is necessary for this to continue to be an accessible transportation mode."