A new study has busted the decades-old myth that transit systems get less efficient when they receive more government subsidies — and proved that subsidies, in fact, do the opposite.

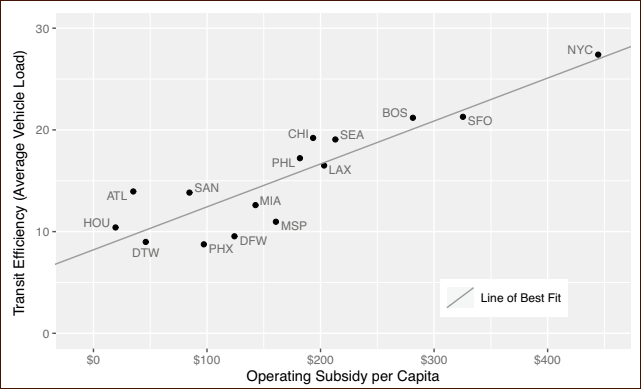

In a fascinating recent analysis, researchers found that metro areas that received more government subsidies per capita were more likely to run buses and trains with lots of passengers on board, rather than running inefficient, wasteful routes with just a few heavily subsidized riders per vehicle.

That simple-but-radical finding flies in the face of the common assumption that operating subsidies hamper efficiency — or, as Randal O'Toole once colorfully wrote for the Cato Institute, that the "great experiment of socializing public transit has failed" because it "failed to boost ridership or stabilize the industry." That alleged inefficiency, detractors argue, means we should stop pouring government dollars into mass modes, and re-privatize transit networks so they can finally pay for themselves — "at least until driverless cars make buses obsolete," O'Toole wrote.

The new analysis, though, debunks that troubling argument — and it could have particularly huge implications for our national conversation about federal transit operations subsidies, which was recently re-opened in Washington and has gained particular urgency since the Covid pandemic.

"We were flabbergasted by the outcome; it wasn't what I expected at all," said Gregory Newmark, an associate professor at Morgan State University and a co-author of the paper. "Basically, we think people have been measuring this all wrong."

The first thing that most researchers get wrong about the impacts of subsidies on efficiency, Newmark explains, is that they tend to measure that efficiency at the level of the individual transit agency — even in metros with multiple operators that riders move seamlessly between.

"That is not how any rider sees their transit system," he added. "The Bay Area, for example, has 26 transit agencies; if you transfer from a bus to a BART train using the same fare media, you're not super sensitive to the fact that those are two separate operators. You see it as one unified system, which is the way it should be."

Newmark's study, by contrast, defined "transit" as all the vehicles in an urbanized area's "transitshed," regardless of which agency's name is on the side of the vehicle. And it also used a more-intuitive definition of "efficiency," which previous researchers have variously used to refer to just about everything under the sun — including costs per vehicle-mile, costs per hour, costs per passenger, vehicle miles per employee or per vehicle, as well as complicated metrics that combine several of those variables into one.

Instead, the new study looks at the simple ratio between how many miles transit passengers in the region collectively travel and how many miles transit vehicles in that region collectively travel, giving a clear, easy-to-understand picture of how crowded (or empty) subsidized buses and trains are likely to be.

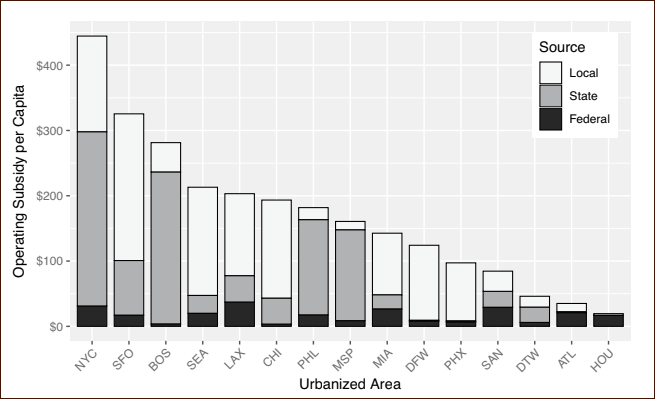

Finally, Newmark's analysis looked at how much subsidy each transit system receives per capita, rather than per rider, as well as whether that subsidy was likely to come from federal, state or local sources.

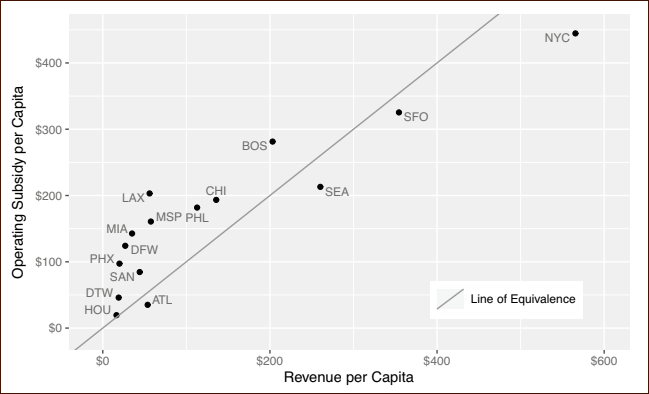

With those clearly defined variables in mind, Newmark and his colleagues found that the regions receiving the highest levels of subsidy were the most efficient — and, interestingly, they also generated the most revenue from fares.

New York City, for instance, subsidized transit to the tune of a whopping $445 per resident per year between 2016 and 2019, but generated $565 in revenue and had the highest efficiency score of any region in America, with an average of 27.4 passengers per vehicle during the study period. Car-dominated Phoenix, by contrast, received just $97 in subsidies per person annually, collected only $20 per person in revenues, and had the lowest efficiency score by far, with just 8.7 people aboard every bus and train.

Put another way: contrary to their detractors, operating subsides don't seem to make enfeebled agencies increasingly dependent on government dollars while unleashing legions of mostly empty buses on U.S. streets. Instead, they seem to provide a strong foundation for transit networks to thrive — and ultimately, make significantly more money at the farebox than they would without support.

Newmark's study doesn't definitively determine why, exactly, high subsidies seem to correlate with better efficiency and transit agencies collecting more fares, but he has some theories. Some systems, he says, use subsidies to increase service frequency or install dedicated lanes to speed routes up along heavily-utilized corridors — and riders are responding, predictably, by showing up in droves. (Route expansion can help, too, he said, but only if agencies expand service to places "where there's actual demand.") Others use subsidies to keep ticket prices low, but not to eliminate fares outright, which Newmark argues is a smart move.

“People value stuff they pay for, and they pay for stuff they value," Newmark added. "An underlying point in this paper is that transit offers something [valuable], and it's worth trying to capture that value, whether through fares or in other ways."

If transit networks and the taxpayers who support them can get that recipe right, it could create a virtuous cycle.

"If people see the benefits [of subsidies], that may make them more willing to invest [their taxpayer dollars]," he adds. "Good transit leads to a real social movement for more subsidies.”