America's shared micromobility operators are rarely obligated to fulfill a robust range of equity requirements by the cities in which they operate, a new study finds — and asking more of them could be critical to giving underserved communities the non-automotive mobility options they need.

The recent University of Oregon study found that only 62 percent of bike and scooter-share programs in U.S. cities are required by cities to meet at least one equity-focused mandate — such as reduced fares for low-income riders, adaptive vehicles for people with disabilities, or cash payment options for the unbanked.

Only 46 percent of programs, meanwhile, must meet at least two mandates, and only 29 percent specified that operators needed to do targeted outreach to the underserved communities they hoped to get riding, which the researchers argue could create "potential challenges for travelers facing intersectional barriers."

Most experts believe that great divide is already happening. Surveys of riders in Minneapolis, Santa Monica and many, many, more have repeatedly found that micromobility riders are disproportionately White and higher-income, even as low-income households of color in those communities report the greatest needs for better mobility choices.

Worse, few city leaders the researchers spoke with seemed to even know what equity benchmarks they could aim for — or which ones would actually get their underserved residents riding.

“When we talked to cities, some of them felt like, ‘I'm a small community; I don't have power to ask, or require, these different program elements.’ … Or there just wasn't certainty about how [to] write those regulations," said Anne Brown, the lead author of the study. "I think our goal with this was really providing more transparency into this process and what cities across the country are doing.”

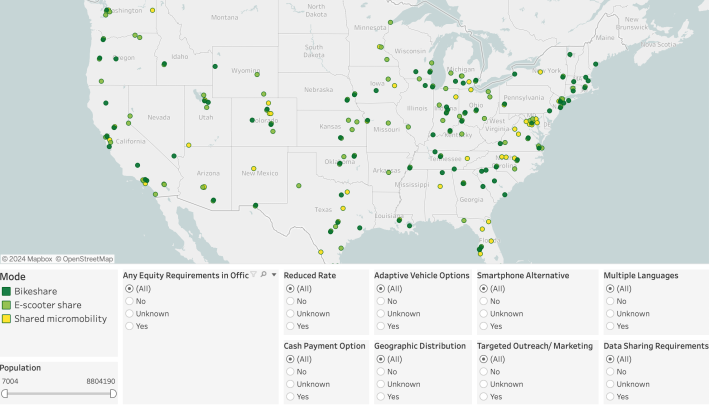

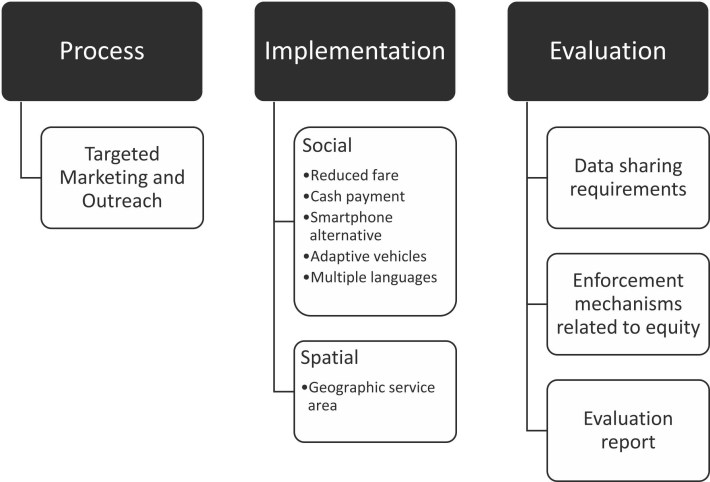

To expose the gaps, Brown and her co-author pored over policy data for 239 micromobility programs across the U.S. to create an interactive map that communities can reference when they're writing their next program permit. In the process, they identified a universe of strategies that can help put shared, safe, green options within reach of more people— and not just by physically placing bikes and scooters in underserved neighborhoods.

"It doesn't really matter if you have a bike or scooter on your street if you can't use it, right?" added Brown. "[You have to ask:] Can you afford to unlock and ride that biker scooter? Do you have a smartphone? Do you have a bank account to access that [app]? Is it in a language that is usable for you? Is the vehicle type actually appropriate for you to use — is it accessible in that way?"

Without those sort of requirements, Brown fears that cities are over-relying on the good will of private operators, who ultimately have to make a profit even if mobility justice goals feature prominently in their mission statements. Some operators, for instance, offer blanket fare-reduction programs for low-income neighborhoods that Brown didn't include in her study, because those operators aren't always tasked by cities to continue those discounts indefinitely.

"The city's goal, often, is to look out for the public good and for the mobility of residents — and hopefully, to protect and support mobility among the least advantaged groups … [But] these same groups, who may have fewest resources, are not the ones that the private companies would necessarily initially target, right?" added Brown. "Because they're probably not where you're going to make most of your money, and in order to operate, these the mobility operators need to collect fares."

Brown also argues that cities should be more proactive about tailoring their equity requirements to their unique community challenges, and collecting great data to figure out which ones work and which ones don't. The best fare discounts in the world, for instance, might not matter much in a city where there's nowhere safe to ride, while a city rich in bike lanes might still need to fine-tune its fare discounts to reach key riders.

"All these requirements vary tremendously across cities, which I think is one of the most interesting things we observe," she added. "There's [just] not a good understanding about which ones work better than others ... Some cities said something very broad, like, ‘operators must provide discounted rates for people earning low incomes.’ Others were very, very prescriptive, and would say something more like ‘operators must offer 30 min of free rides to anyone who earns up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level.’ So there's a huge variation in what cities actually required in that language, and we don't yet have a great understanding of how much these very specific pieces matter."

Brown acknowledges that there's no one-size-fits-all slate of equity policies that will make micromobility truly accessible to everyone. By taking a birds-eye view of how U.S. communities are tackling that challenge, though, she hopes that she can inspire better policies nationwide — and maybe even prompt a conversation about why we don't hold our dominant transportation system to a similarly high standard.

"We put all these burdens on [micromoblity providers]. But what about the cars?" she adds. "They're the ones who are really costing us. [While I’d argue] it's important to make sure the car alternatives are affordable themselves — [and] I'm glad that the cities are putting that [responsibility] on them — I wish they would also [pursue] broader policies to support everyone."