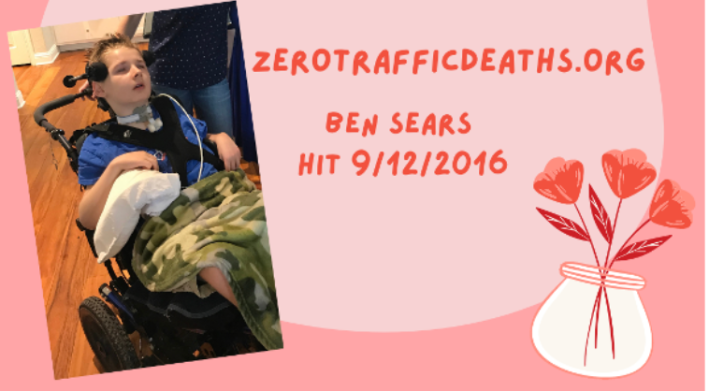

When 9-year-old Ben Sears was struck by a pick-up truck driver while crossing the street in 2016, he became yet another one of the tens of thousands of U.S. residents who fall victim to traffic violence every year. For Ben's loved ones, though, the pain of seeing the smart, funny little boy they knew reduced to a statistic would eventually be compounded by a cruel bureaucratic reality: Ben's death would not even count towards federal crash fatality totals, because he did not succumb to his injuries quickly enough.

Since it first launched 1975, the federal Fatality Analysis and Reporting System database has excluded all car crash deaths that occur more than 30 days after the initial collision. That means people like Ben — who lived with a traumatic brain injury, a severed spinal cord, an inability to speak, and other major disabilities for five years before he died — aren't included in official annual death totals.

Survivors say those stats also don't capture the sheer scale of the grief, horror, and hardship suffered by victims and their families, whether they succumb to their injuries immediately or manage to hang on.

"You lose them twice," said Kathy Sokolic, Ben's aunt and co-founder of Central Texas Families for Safe Streets. "We lost the person that Ben was in that crash, and we grieved him just being in that body, and having to take care of that body that was a shadow of who he was. And then you lost him again when he actually passed."

'It's actually even worse'

Of course, America's traffic violence numbers are damning enough even without deaths like Ben's on the books. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration reported 42,514 deaths in 2022 alone, which is almost triple most other industrialized nations' per-capita road fatality rates. And for pedestrian deaths, those disparities are even sharper, with the U.S. hitting a 40-year record high as other countries' walking casualties trended sharply down.

The National Safety Council, though, estimates that overall car crash deaths were at least 8 percent higher than those numbers that year, at least when you include deaths that occur up to a year after a collision, and those that occur anywhere besides a public road. And while that still wouldn't include deaths like Ben's, some advocates say it'd at least be a start if federal officials expanded their scope.

"We're already performing so poorly compared to other nations, but it's actually even worse than the numbers they release," said Amy Cohen, co-founder of the national organization, Families for Safe Streets. "If the National Safety Council is able to collect that data, then so should NHTSA."

Cohen argues, though, that NHTSA's exclusion criteria are a symptom of a larger problem with how the agency counts serious injuries that upend families' lives and often lead to death — or, more accurately, how they don't count them.

For instance, while federal regulators recorded nearly 2.4 million car-crash related casualties in 2022, the National Safety Council estimated that there more than twice as many people were actually hurt by drivers that year. Moreover, both figures lump together "non-disabling" incidents that left victims with bumps and bruises and with crashes that left them permanently bedridden.

On top of that, some experts believe that at least half of pedestrian and cyclist crashes aren't recorded in federal databases at all, in part because police generally aren't required to report collisions when the victim isn't transported to the hospital by ambulance — even if they later die of an injury that wasn't discovered at the scene.

And then there's all the uncounted deaths that are profoundly linked to the trauma of a crash, but not directly caused by crash-related injuries, including when victims later die by suicide, because of complications from substance abuse disorders developed in the wake of a collision, or because a crash left them unable to work and they fell into homelessness.

“For those injured in a traffic crash — including those who die and those who survive — their lifespans are often shortened, and their lives are forever altered," added Cohen. "They never achieve the full potential that they had before."

Both Cohen and Sokolic say they wish the suffering of victims' families counted, too, though they understand all too well how challenging it would be to quantify that pain from a public health perspective. In Sokolic's case, Ben required 24/7 care following the crash, and battling Medicaid to get him the therapies he needed became "almost a part time job" for Ben's parents. Those challenges became even more difficult to bear as Ben's body lost the ability to absorb nutrients and the family tried "every medical intervention they could think of" to keep him nourished; ultimately, they'd exhausted all their options, and Ben entered hospice.

"They were in limbo for five years," she added. "You can't just take a quick weekend get away, or just go out to see a friend or run out to a concert. You feel so guilty for leaving your child. They barely left the house for five years — and their health really suffered for that."

Even though she was not Ben's primary caregiver, Sokolic also struggled in the wake of his crash. She's paid for therapy for years, especially after the driver who struck Ben — who was never charged with a crime — rented a commercial space on the block where she lives. Every day, she had to see the pick-up truck that changed her family's lives forever parked right outside her home.

"It kind of broke me," she adds. "I used to be a person who had this excessive amount of energy. Now that's just gone."

More than a number

When asked by Streetsblog why victims like Ben aren't included in federal death totals, NHTSA cited data that estimates 98 percent of people who die in car crashes will succumb to their injuries within 30 days of their collision, as well as the necessity of "maintain[ing] uniformity for those who report, analyze, classify, and otherwise use traffic crash data."

Because America's traffic violence epidemic is so massive, though, that 2 percent represented a stunning 867 people in 2022 alone, many of whom left behind grieving loved ones whose lives, livelihoods, and futures were profoundly altered by their experiences.

It includes 17-year-old student-athlete Khameryn Oliver, who died more than two months after a crash that killed both her parents; it includes 37-year-old Christopher Hoeckel, who was struck while walking to an Annapolis McDonalds and survived his injuries for three months before dying; it includes 4-month-old Mason Lewis, who spent half of his tragically short life in hospitals; it includes Anthony Avelo, 63, who spent 12 years unconscious in a Brooklyn rehab center while family members waited for hope that never came. And it represents the countless other victims whose stories are reported only briefly in local news outlets, if at all.

And for survivors like Sokolic, it also represents an opportunity to further underline just how badly America needs broad, systemic reform to save other victims and their loved ones such unthinkable pain. In the past eight years, she's fought for lower speed limits on residential streets like the 30 mile per hour road where Ben was struck, and successfully managed to get the word "accident" removed from Texas' state transportation code, among other victories. And she hopes that by continuing to tell her story, she can inspire more change — and more empathy for victims whose deaths too often don't count as preventable tragedies in the minds of policymakers, if they're even counted at all.

"Creating just a little bit more understanding of what this means to people's everyday lives, so we can change policy to help prevent some of these crashes — that would be huge," she adds.