America would reap massive public health and emissions-reduction benefits from electrifying its bus fleet, a new study confirms — even if we only replace the diesel buses that are too old to run anyway, or focus all our energies on greening the largest cities alone.

Contrary to the weirdly persistent myth that e-buses don’t really cut pollution when you factor in things like the emissions required to produce and charge them, a recent study from Carnegie Mellon University found that electrifying America’s bus fleet could slash between one- and two-thirds of the fleet’s total greenhouse gases over the next 14 years, depending on how quickly we do it.

And the study authors argue there are good reasons to act fast. Aside from greenhouse gases, diesel buses spew a range of toxic PM 2.5 particulates over the dense city neighborhoods where they’re most often run, disproportionately impacting marginalized communities who they say inhale between 56 and 63 percent more of those pollutants than they produce as a result of their own transportation behavior.

Some advocates have argued we could reduce those environmental impacts even faster by simply improving bus service to get Americans out of cars — cars which, needless to say, produce far more PM 2.5 and greenhouse gases per user than even the dirtiest buses around — but the Carnegie Mellon team says we can and should do both.

“In an ideal future, all of that stuff would happen,” said Sofia Martinez, lead author of the study. “Diesel buses have a lot of particulate matter emissions, too, which can impact people's air quality and their health — especially if they have asthma, [which makes residents] very sensitive to it.”

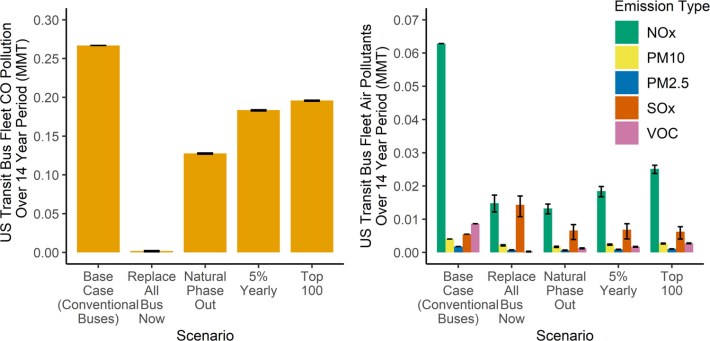

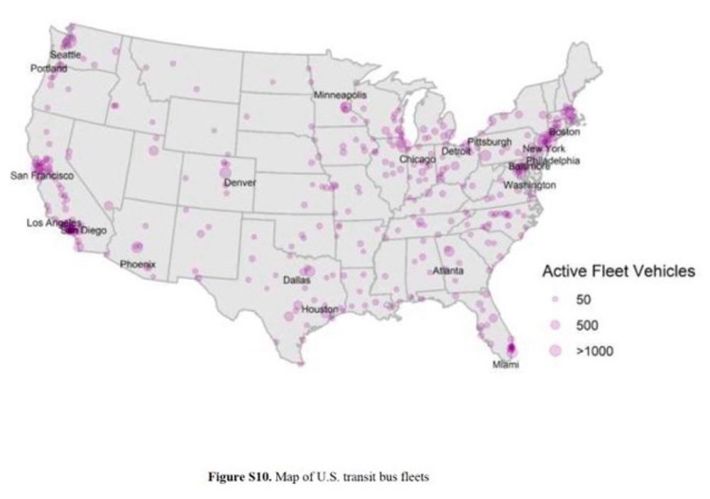

Based on an analysis of Federal Transit Administration data on every bus route in America in 2021, the CMU researchers found that if we could “wave a magic wand” and swap out every diesel bus on the road — a prospect that they estimate would cost $39.5 billion — America could zap an astonishing 40 million metric tons of greenhouse gases from our skies by 2035. That’s even accounting for complex factors like the daily driving ranges of those buses, how many passengers each vehicle can sit, and how big the batteries would need to be to cover the whole route without stopping to re-charge until the service day ends.

Even simply replacing diesel buses with electric ones as they naturally age out of service, though, would still cut 35 million metric tons of CO2 by the 2035 deadline – and it could be done at the cost of just $8.5 billion to start, plus $2 billion to $3 billion a year every year until all the gas-guzzlers were gone. Proactively replacing 5 percent of the diesel bus fleet each year, meanwhile, would eliminate 25 million tons of greenhouse gases and cost taxpayers $3.1 billion a year, while greening the 100 largest transit agencies’ vehicles alone would cost $31 billion and slash 20 million metric tons.

Martinez said even that less-ambitious final option, though, may still deliver the greatest public health bang for our buck, considering that it would remove pollutants from virtually all of America’s most densely populated neighborhoods. And it would still deliver climate change benefits roughly equivalent to removing 4.7 million private cars from the road for a whole year.

“To me, the scenario that feels most feasible is probably transitioning the largest 100 agencies,” she added. “Even though it's the slowest, it still mitigates about 33 percent of the greenhouse gases from the base case scenario [and it] clears out emissions from the most populated city centers. Whereas in rural areas, maybe there's a bit more open air and space for these [emissions] to air out and not necessarily impact people's health as much.”

Of course, Martinez acknowledged that electrifying America’s bus fleet won’t be easy. Aside from the perennial political challenges of diverting money for transit from drivers, her study couldn’t account for things like critical material shortages if bus manufacturers are forced to compete with e-car manufacturers for scarce battery minerals, or how the cost of “refueling” an e-bus might increase in cities that charge more to plug in during peak demand hours.

Still, the researchers say there’s already enough evidence to make the case for more federal e-bus subsidies — and to determine exactly how much money agencies need to make rapid electrification a reality. Specifically, the study found that “with falling capital costs and an increase in annual passenger-kilometers of battery electric buses, the technology could reach levelized cost parity with diesel buses when electric bus capital costs fall below about $670 000 per bus.”

Put another way: though the average BEB costs a sky-high $745,000 right now, the technology is improving quickly enough that it’ll soon be nearly cost-competitive with diesel — especially when you factor in the public health costs of diesel-linked air pollution, which the $670,000 number doesn’t. And with the Biden administration already investing $5.6 billion into bus electrification over five years, the researchers say it’s worth it to increase government subsidies to bring costs all the way down to that magic number — and do whatever else we can to bring emissions down and transit ridership up.

“We definitely need to be advocates for electrification, and for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and air pollutants in any way we can,” Martinez says. “But don't necessarily let yourself be restricted to one solution — because the future is going to involve every kind of solutions that we can get our hands on.”