The percentage of dead motorists who had fentanyl in their systems when they crashed has doubled in recent years, a new study finds — but with testing, legislation, and meaningful solutions still severely limited, experts fear that the true scope of the problem may be even bigger.

According to a recent analysis from the digital insurance broker Jerry, a disturbing four percent of all drivers who were tested for drugs following a fatal crash in 2021 were found to have the potent synthetic opioid in their system, up from two percent in 2018.

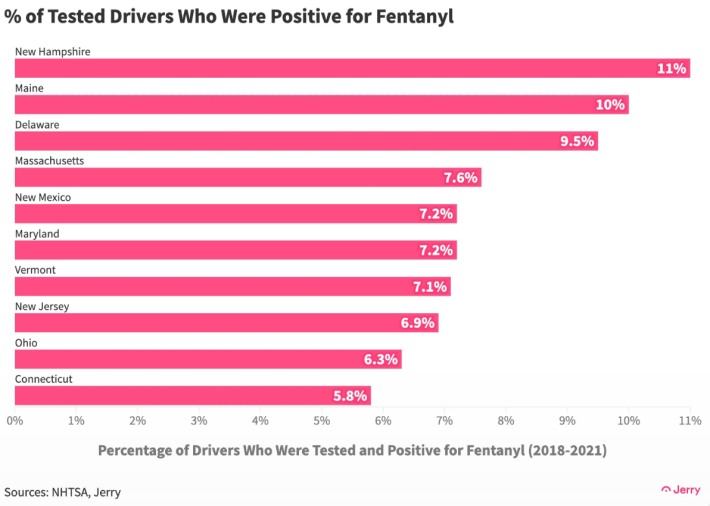

And that increase may be an undercount. The study authors say only 37 percent of drivers involved in fatal crashes were even tested for impairing substances during the study period, and that testing rates vary "dramatically" between states — which could help explain why some smaller communities, like New Hampshire, had fentanyl test positivity rates as high as 11 percent of all motorists who received a test after being involved in deadly wrecks.

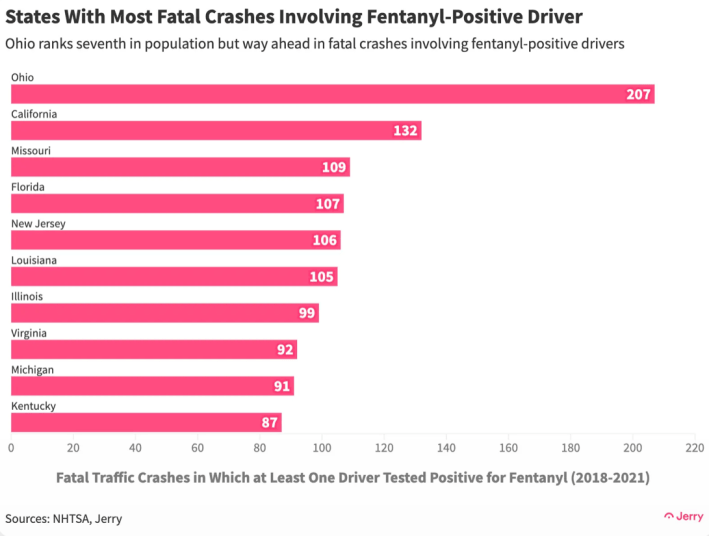

Ohio, meanwhile, had the highest rate of per-capita crashes involving fentanyl, though it wasn't clear whether that was because the Buckeye State administered more tests than other communities. Nearby West Virginia didn't make either list, despite a nation-leading rate of drug overdoses that has been driven in large part by the rise of fentanyl in recent years.

The study authors say even that incomplete data, though, suggests a disturbing trend about which policymakers need to be proactive.

"Four percent is four percent too many," said Henry Hoenig, data journalist and author of the study. "There’s not enough testing; only in about half of fatal crashes is even one driver given a drug test. ... I think every driver should be tested; I’m not sure why they aren’t."

That question is becoming more urgent by the day as fentanyl use surges across America — and as countless American communities remain profoundly car-dependent in the face of it.

A recent UCLA study, for instance, found that national overdose deaths involving the substance have increased 50 fold since 2010, and that the epidemic is rapidly accelerating.

As that tidal wave rises, though, research into how fentanyl impacts driving, specifically, remains scarce. One 2021 study, for instance, found that motorists who took only the schedule II substance were frequently "found unresponsive behind the wheel" or in vehicles that had run off of the road, and in many cases, that dangerous behavior had ended in a crash.

That study, though, only included 20 motorists, in part because fentanyl is often taken in combination with other substances and incidents where it was used in isolation were hard to find. A 2003 study, meanwhile, found that pain patients who took controlled doses of fentanyl in a medical setting did not show signs of driving impairment, but it did not include recreational users who took higher doses.

On top of that, because fentanyl is frequently cut into other drugs — and because drugs are often taken in combination with alcohol behind the wheel — spotting its use in a roadway context can be complicated and expensive, "to the point that when officers encounter someone who has consumed both alcohol and another drug, they are often discouraged from investigating the drugs," the Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association wrote in a 2022 report.

The same report also said that "when prosecutors can charge a defendant with driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs, they often pursue the alcohol charge alone," because "proving drugged driving charges requires presenting more technical evidence and convincing skeptical juries."

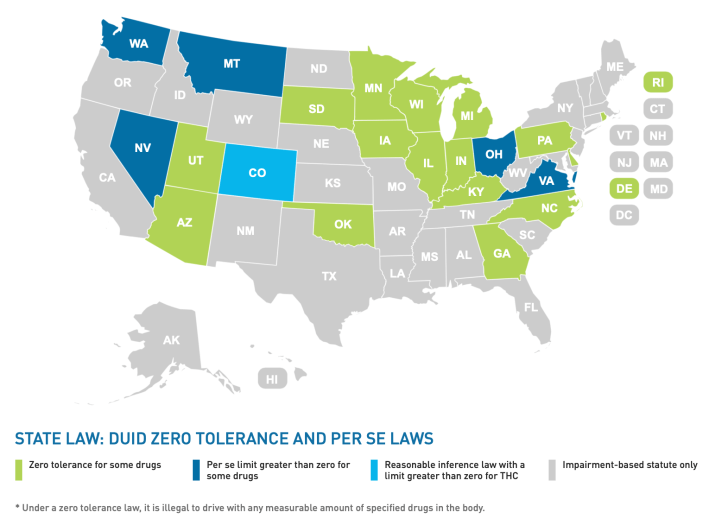

In the absence of scientific consensus or public awareness about its possible effects at various dosages, fentanyl intoxication behind the wheel has fallen into a murky political space. In the 16 states that have zero tolerance laws for drugged driving, it's illegal to operate a car with any amount of fentanyl in one's system; in the remainder, though, fentanyl use falls under the vague umbrella of laws that prohibit driving "under the influence" in general, with some states failing to specify what that actually means in practice. None of the five states with "per se" laws that set non-zero limits for some drugs do so for fentanyl.

As states attempt to craft meaningful policies that reflect the evolving impact of fentanyl on our roads, transportation leaders shouldn't overlook the importance of connecting people to addiction treatment when they use in the transportation realm, not to mention giving people alternatives to driving, like safe walking, biking, and transit routes. And as contentious as those conversations can be — particularly the last one — we owe it to ourselves not to shrug off patchwork statistics and confront the impact of the opioid epidemic head on, and with as much compassion as possible for everyone with whom we share the road.