A recent shift in how the federal government measures Americans' travel behavior may have undercounted walking trips by more than half — and as transportation leaders look to that flawed data to make infrastructure decisions, it could have dire implications for the pedestrian of tomorrow.

In December of last year, sustainable transportation advocates were shocked when the feds announced that walking trips had plunged to just 6.8 percent of all journeys taken on U.S. roads, down from 10.5 percent from five years prior. That works out to a shocking 60-percent drop in total pedestrian journeys — and it seemingly occurred alongside a 38-percent reduction in trips on any mode, prompting speculation that Americans on the whole are both leaving home less and choosing motorized modes when they do.

The 5-year National Household Travel Survey (#NHTS) is now available. In 2022, household travel decreased compared to 2017, with rural residents traveling nearly as much as urban dwellers. https://t.co/zdTnfGodsZ pic.twitter.com/tv3dsarYTK

— Federal Highway Admn (@USDOTFHWA) December 11, 2023

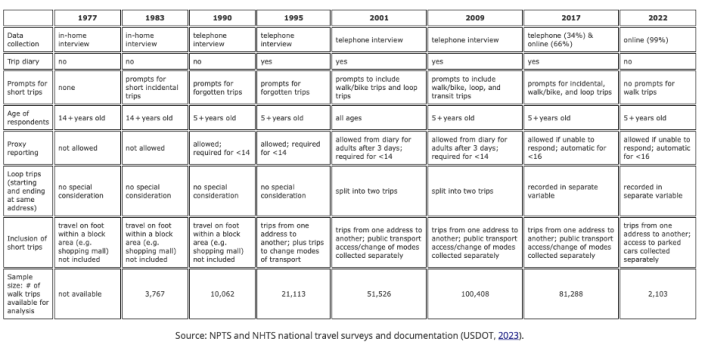

That alarming data came from the National Household Travel Survey, which for 54 years has gauged Americans' typical travel patterns based on a series of 24-hour samples taken roughly every five years. The study has historically faced criticism for its constantly shifting methodology, which has, at various points, failed to account for walking at all, under-counted walking trips that start and end at the same destination, or ignored the mobility behavior of most kids who are too young to drive.

Even in its most problematic iterations, though, the data from the survey has maintained a major influence over how transportation leaders allocate funding and resources to active modes — or how much they don't.

"In a nutshell, what's not measured cannot be planned for, so we have to be able to measure walking in order to plan for it," said Ralph Buehler of Virginia Tech, who co-wrote a new study on recent changes to the survey's methodology. "And if you look back at the history of transportation planning, we’ve never really planned for walking. ... To build networks for pedestrians, to build crosswalks, sidewalks, traffic lights, we first have to measure walking, and we have to measure it well. And we're still, unfortunately, in the infancy of doing that, because our systems have historically focused on driving."

Buehler and other researchers say walking trips probably did decline somewhat during the pandemic, especially considering the well-documented decline in transit trips that often start and end with a walk to a stop. They argue, though, that the most recent National Household Travel Survey was based on particularly flawed data that significantly oversold how steep that drop-off was — despite the fact that the Federal Highway Administration still describes the survey as "the authoritative source on the travel behavior of the American public."

First, the sample size for the most recent survey was slashed 94 percent from the previous edition, recording only 2,103 walk trips, 341 public transit trips, and 298 cycling trips for the entire country, which the agency then extrapolated out across the calendar year. Buehler and his co-author, John Pucher, say that such an "extraordinarily small national sample does not permit reliable statistical estimates for some kinds of analysis, especially detailed disaggregation by social, demographic, geographic, and economic dimensions."

Worse, the recent survey was also the first to be conducted entirely online, rather than allowing at least some participants to work with a telephone interviewer trained to prompt participants to remember the kind of short, easy-to-forget trips Americans tend to take on foot — and excluding anyone without access to a computer. It also eliminated the long-standing tradition of having participants complete a trip "diary" in real time, relying instead on what they could later recall about where they went and how they'd gotten there.

The agency also omitted a crucial question about whether respondents had walked to a transit stop, which is how more than 90 percent of Americans got to their bus and train stops during previous survey years — but it added a question about how long it took drivers to walk from their parked cars to their final destinations and back.

"They increased the number of questions for motorized travel, and they reduced the number of questions about walking and access to public transport," added Pucher. "In a sense, it’s almost like discrimination against sustainable transportation modes."

Both Pucher and Buehler emphasize that "discrimination" probably isn't deliberate — even if it could have deeply inequitable impacts on people who don't drive. Since the survey was last issued, more transportation officials have begun to rely on inexpensive anonymized travel data collected from cell phones, which isn't subject to fallible human memories, covers millions of people, and is monitored year-round, rather than on a single day alone.

Buehler argued, though, that for all its flaws, the National Household Travel Survey still delivers critical information that policymakers ignore at their peril. Surveys, for one, can actually confirm critical demographic information about who Americans are and why they're traveling — big mobility data can only infer that information, at least without committing massive privacy violations — and it doesn't cover people who don't have cell phones, including many children, whose mobility behavior is recorded in the NHTS if they're above the age of five.

Moreover, he believes that over-reliance on big data can sap enthusiasm and money for more granular interviews with road users — and without a human being to remind Americans about that midday coffee run they took on foot, driving often appears more dominant than it actually is.

"I don't think anybody sat down and said, ‘Oh, we're going to delete this walking data because we don't like it,'" Buehler added. "But it’s the Federal Highway Administration, right? So the mindset is that they are collecting data on roadways and on cars.”

A better approach, the researchers argue, would be to combine the power of well-formulated surveys with technology, inviting volunteers to complement their passively collected travel data with an in-app diary that details what those trips were for, and corrects any mistakes the AI made. Cities and states, meanwhile, could complement national surveys with data collected from roadside pedestrian counters, pen-and-paper pedestrian counts, and local surveys of their own.

However they do it, the researchers stress that America badly needs better walking data — not just to guide our transportation decisions, but to reflect the important role that walking can play in public health, civic life, and more. And they also argue that the most recent version of the survey isn't cutting it.

"It's just shows how little importance the people in charge seem to attach to sustainable modes of transportation," added Pucher.