Even a “15-minute city” that’s perfect on paper may still leave residents’ basic needs out of reach — especially if planners assume they understand what diverse populations want without actually asking them, a new study suggests.

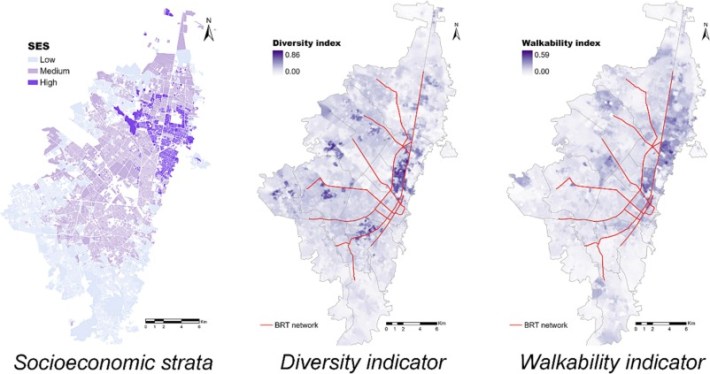

Researchers in Bogotá developed a new model to assess how close neighborhoods in the Colombian capital are to actually achieving the “ciudad de quince minutos” ideal, which aims to put essential services like work, shopping, education, groceries and leisure within a 15-minute walk, bike, or transit ride of every home.

That ideal, though, isn't without controversy, their new paper shows. Some scholars have argued that “chrono-urbanism” — an academic term for planning that emphasizes maximum travel times on green modes — doesn’t tell the whole story of why residents are spending so much time on the go, especially in communities with high rates of social inequality.

“[The 15-minute city] sounds very nice; Who doesn't want to get everything very close to home?” said Luis Guzman, the lead author of the paper. “But what happens when [cities are] segregated, with so many people living in neighborhoods without any real access to so many basic urban services?”

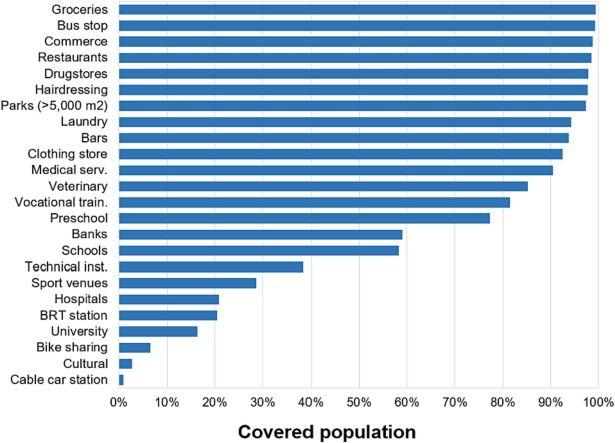

Unlike other studies, the Bogotá researchers began by surveying real people about which of those amenities were most important to them, and what specific versions of those services best met their actual needs. And after they’d determined, for instance, which households wanted to leave near a preschool versus a college campus, they also analyzed the other barriers to sustainable mobility that might stand in those residents’ way, including poor pedestrian infrastructure or fears of street violence — and how real people rated those barriers when they made their actual travel choices.

“The wisdom of the urban planner says, ‘Don't worry about your needs; I know what you need; you need recreation, education, and health, and so forth,'” added Guzman. “Our study is trying to fill the gap in knowledge in the international literature, and to highlight [the fact] that people’s needs are more important than planners’ ideas.”

In Bogotá, at least, researchers found that low-income residents were far more likely to list healthcare access as a must, while high-income residents placed more weight on the proximity of retail shops. People of all backgrounds, meanwhile, emphasized that their “personal security” was a major factor in whether they walked or not, particularly when it came to fears of robbery and traffic violence.

“[Walkers] suffer not only because of the lack of the pedestrian infrastructure, but also because there are other issues like personal security, violence, robberies, and pollution," added Guzman. “So what if I’ve got a lot of services near my home [but] walking there isn’t so nice?”

Guzman was careful to note that just because proximity isn't everything doesn't mean it doesn't matter at all — and that planners shouldn't bow to conspiracy theories that claim building more services in our neighborhoods will somehow force residents to never leave their neck of the woods.

“I’m sorry that I don’t know another English word for this, but this is bullshit,” laughed Guzman. “It’s not a mandatory thing. … if there’s a movie theater in my neighborhood, there’s nothing that’s forbidding me from going to another movie theater on the other side of the city. I think all chrono-urbanism is trying to do is give alternatives in proximity to houses. Ideally, it’s giving attractive alternatives. But if I want to go other places, I can.”

Still, Guzman says that for true 15-minute cities to be a reality, we need to have a deeper conversation not just about how long it takes to get places, but about whether we enjoy the journey or the destination — and how our answers to those questions change based on the societal inequalities that impact us.

“We’re asking: is proximity enough?” he added. “And also, in a parallel way, we're asking, 'Well, what happens in neighborhoods that already have a lot of services nearby, but walking from homes to those services is awful?'”