Cell phone use behind the wheel skyrocketed during the pandemic, even among drivers whose insurance companies rewarded them for keeping phones stashed — raising troubling questions about how much more distracted driving will occur if America doesn't take steps to reduce driving itself.

According to a new report, "distracted driving" events — or, more specifically, a motorist picking up a hand-held phone and manipulating the screen while the vehicle is moving 10 mph or more — increased around 20 percent between the early days of 2020 and 2022. And that doesn't even include harder-to-track but still dangerous distraction events, like flicking through an "infotainment" screen embedded in a dashboard, or using phones hands-free, which studies show is deadly, too.

That's according to Cambridge Mobile Telematics, a technology company that monitors the behavior of drivers who opt in to programs that give them insurance discounts in exchange for safe behavior.

The most horrific finding? Roughly 34 percent of crashes recorded among the company's customers involved a driver who had been using a cell phone either at the time of impact, or at some point in the 60 seconds immediately before the crash, when studies show motorists are still shaking off a "distraction hangover" that slows their response times even after the phone has left their hands.

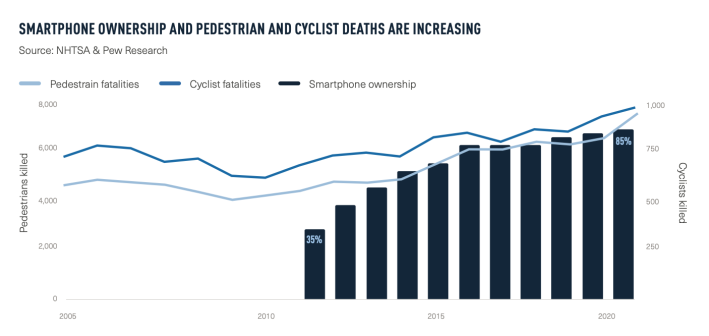

And the researchers suspect the reason behind the increase is less about COVID than our increasing reliance on smartphones themselves — a phenomenon which the isolation of the pandemic helped increase, but which probably won't slow down as case counts wane.

"As individuals have begun using smartphones for more parts of their life, they've continued to do that behind the wheel," said Ryan McMahon, senior vice president of strategy at Cambridge Mobile Telematics. "The problem got significantly worse in March 2020, and then it started to accelerate very quickly."

If he's right, distracted driving could prove a uniquely tricky problem to solve.

Over the past 15 years, McMahon said, the very boundary between the core functions of the car and the cell phone has become increasingly porous, with navigation, entertainment, and emergency services features migrating from tactile dashboard buttons onto the phone screen itself. And thanks to America's unique culture of overwork, some pundits argue that the boundaries between the daily commute and the rest of daily life have eroded, too, as Zoom meetings bleed over from the office to the drive home, and caretakers text to check in on relatives as they zip from daycare drop-off to the grocery store — even if they know they really should pull over first.

When remote work and flexible, errand-rich schedules skyrocketed during the pandemic, multi-tasking behind the wheel skyrocketed, too, along with the deaths of vulnerable road users — even as the overall amount that Americans traveled by any mode plummeted.

Short of requiring U.S. residents to transition back to the kind of manual transmission cars that require two hands to operate — the predominance of which may help explain why Cambridge customers in the UK recorded about one-third of the distraction events as their US counterparts — McMahon fears that the problem will only get worse, especially as tech companies pour billions into making our phones both impossible to avoid and as distracting as they can possibly be.

“[The] rise in distracted driving, goes back to the launch of the iPhone, frankly," McMahon added. "Shortly after [its introduction], you have the app store, and then you have more and more [of our daily tasks] being conducted on a small piece of glass that's highly mobile and that's with us all the time. ... If you go back in time, you can see a gradual increase in the amount of distraction that very closely pairs with the amount of smartphone ownership by individuals."

McMahon emphasized that there's a lot that America can do to combat distraction behind the wheel ... even if a lot of the most effective strategies are politically impossible.

McMahon added that in-car cell phone blocking technology won't ever take off "unless it's mandated" — something research shows fewer than 38 percent of Americans support. But insurance incentives like the kind his company helps deliver do reduce crash risk by "about 25 percent" compared to if customers received no incentives at all. And while distraction among CMT-equipped drivers is still on the rise, the company suspects that tide could turn, especially as premiums climb and more Americans get fed up with subsidizing the worst drivers on the road.

"The insurance industry is passing along the costs of the deterioration of road safety to every single driver," he said. "Individuals that are not opted into safe driving programs and given incentives for their own safe driving are basically absorbing the cost of every other unsafe driver that's out there, because the insurance industry has no idea who is distracted or not [so they charge everyone more]."

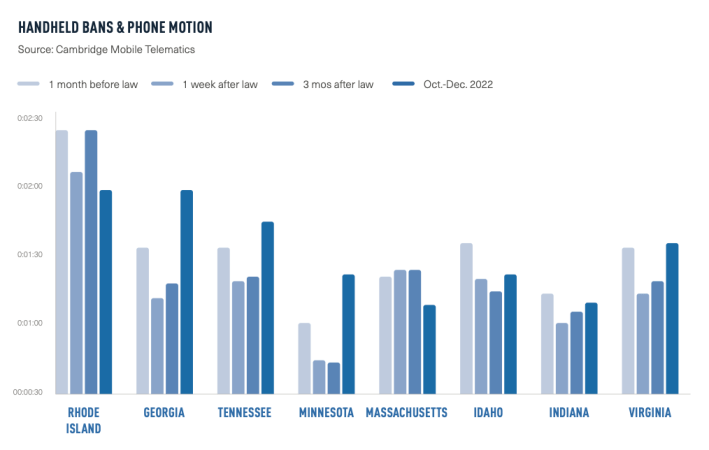

Telematics data also shows that new "hands free" laws have cut cell phone use between 11 and 28 percent, at least in the first months after those bans were put in place. Some states like Rhode Island, though, experienced no change in distraction rates, while others, like Georgia, Tennessee, and Minnesota, reported steep rebounds that suggest a need for further interventions.

Of course, if financial incentives and enforcement disincentives can't cure distraction alone — and considering how wildly enmeshed we're becoming with our devices, they likely can't — we can always turn to strategies to reduce the "driving" half of the distracted driving equation, by shifting Americans onto walking and transit, where distraction doesn't endanger others, or biking, where cell phone use is largely impossible. Because if we don't prioritize the safety and convenience of those modes, we may find ourselves fighting a losing battle.