Mid-sized cities are struggling with unreliable transit service far more than some transportation officials realize, a new report finds — and until we all address the structural reasons behind it, they'll continue to bleed riders.

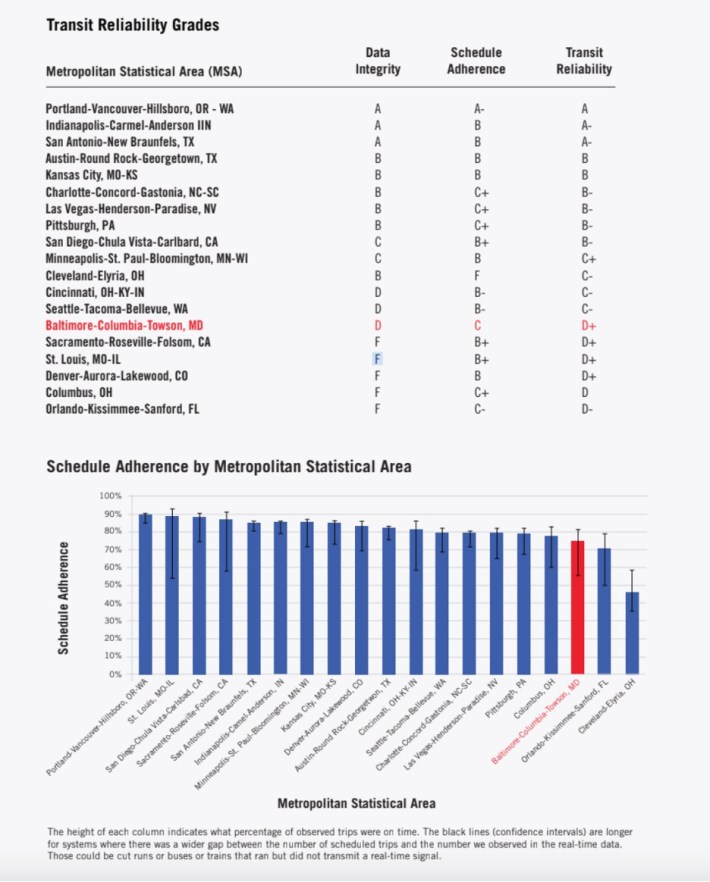

As part of its annual transportation report card, the Central Maryland Transportation Alliance gave its home region of Baltimore a D+ for service reliability, landing it firmly in the bottom third amongst their peer metros on a metric that is often the deciding factor for whether residents ride at all. That barely passing grade helped drag the metro's overall grade down to a D+ as well, indicating that Charm City is failing to provide a transportation system that helps support economic opportunities for residents while building safe and healthy communities where people have a meaningful choice not to drive.

The advocates behind the analysis, though, say that few of the mid-sized metros on the list had an easy time keeping the buses and trains running on time, in part because of the unique challenges of maintaining stable service in relatively less-populous urban areas that often gobble up outsized swaths of land.

Sprawling Orlando, Columbus, Denver, St. Louis and Sacramento, for instance, all ranked even lower than Baltimore for reliability, in part because of a vicious cycle of car dependency that encourages residents and businesses to switch to driving when late or no-show transit lets them down.

In time, that can push residents to live and work on the auto-oriented edges of town and leave transit behind completely, starving agencies of the fares they need to make service improvements and making matters worse for the riders who remain.

"Larger places like Philadelphia, New York, Chicago, or LA all have a greater concentration of destinations people want to go than mid-sized regions, which are struggling to connect [far-flung places]," said Brian O'Malley, the Alliance's president and CEO. "We need to create the virtuous cycle where good public transit has a centralizing effect on where people invest in real estate and create new jobs. And because we've had decades of investment skewed towards roads and highways, that's sometimes a losing battle in these midsize cities."

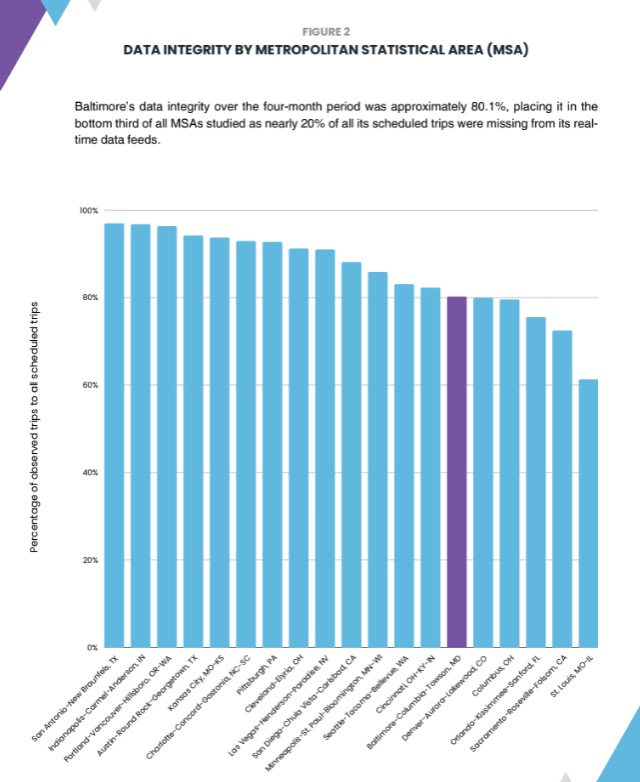

Riders routinely rank frequency and reliability as their top priorities in surveys, yet many mid-sized agencies struggle to even track how dependable their service is, never mind improve it. Until a 2017 network redesign, Baltimore didn't even have GPS on all of its buses or real-time arrival information for passengers, and like many of its lower-ranking peers, it still struggles to make sure signals are working and that operators are using them properly. During a recent four-month study period, a stunning 20 percent of scheduled trips in the city were missing from agencies' data feeds; in St. Louis, nearly 40 percent were.

"Riders deserve to know the truth about whether services are really on the street," said Danielle Sweeney, organizer for the Alliance. "If you can't show that, then your agency is failing."

Of course, some of these "ghost buses" and trains simply aren't in circulation at all, particularly as operator shortages continue to surge across the nation. Those staffing problems are often magnified in mid-sized cities like Baltimore, which are competing for drivers and maintenance workers with better-resourced agencies in bigger cities nearby, like D.C.

And as car dependency deepens, many buses that do make it to the road end up stuck in car traffic, particularly in cities that have yet to build dedicated bus lanes or devote the resources necessary to keep drivers out of them. Accomplishing either is even more challenging in cities with lower population densities, which need more miles of red paint, lane separation, and lane enforcement per capita than a denser metropolis would.

That means that improving reliability will likely require more money for operations and capital projects — especially since it will have to work against a recent tidal wave of federal money for auto-centric projects. The Alliance's director of policy and programs, Eric Norton, says he was initially optimistic that the passage of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act might ease Baltimore's service woes, but so far, he hasn't been impressed.

"Everybody got more, but that also meant that that highways got more — so the priorities didn't change, and everyone just got plussed up," Norton added. "What we're realizing is [this money] isn't going to help us actually shift more people into transit, biking, walking, and get us better outcomes for riders [until we shift that balance]."

The good news, of course, is that some mid-sized cities are keeping the trains (and buses) running; the Greater Portland region was awarded an A grade for transit reliability, and even car-dominated Indianapolis and San Antonio notched A-minuses for their strong mix of schedule adherence and data integrity, even when routes weren't numerous or frequent. And if Baltimore and cities like it can't follow their lead, it doesn't bode well for their ability to deliver everything else a great transit network can provide.

"We hear from people who say they got a job, and they were using transit to get there — but then they were late a couple of times, their boss got angry, and they had to find a different way to get to work," added O'Malley. "It's sort of a deal-breaker if you can't rely on it."