Low-income communities of color are still experiencing dangerous levels of transportation noise generations after their neighborhoods were first targeted for disinvestment and demolition to make way for highways — and that includes their human and animal residents, a new study finds.

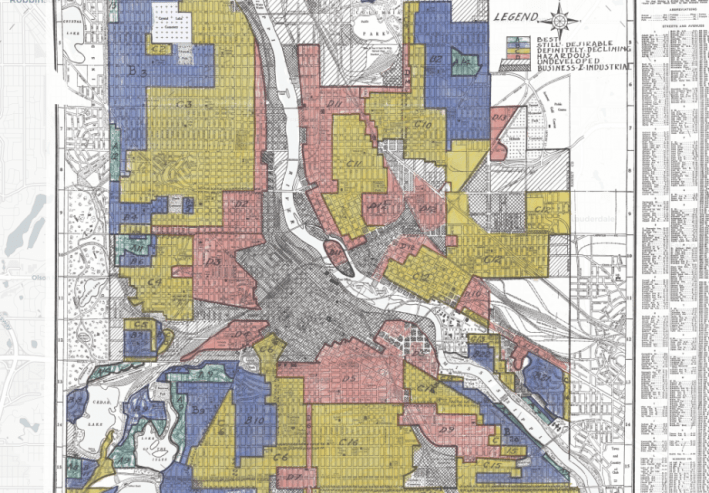

In a fascinating new study of 83 American cities, a team of researchers found that predominantly non-white neighborhoods that were once "redlined" by the federally backed Homeowners Loan Corporation in the 1930s still report dangerous "sound pressure levels" today — especially when compared to "greenlined" neighborhoods, whose residents were (and still are) predominantly white.

A map of redlined neighborhoods in Minneapolis, Minn. Graphic: Mapping Inequality

Today, formerly redlined areas are still predominantly Black, brown, or low-income, too, and they still experience an average maximum noise value of 89.8 decibels — a level which the Centers for Disease Control says can damage hearing after less than two hours of exposure, in addition to increasing stress, disturbing sleep, and provoking a host of other health problems.

That finding might not be particularly surprising to mobility justice advocates, who are well aware of how the infamous maps helped channel investment away from families of color while transforming their communities into "slums" that might as well be torn down to build polluting infrastructure like high-volume roads. Today, addition to noise pollution, redlined neighborhoods experience increased levels of pedestrian deaths, air pollution, flood risk, and myriad other forms of environmental racism.

Less studied, though, is the impact of redlining on the urban wildlife that shares a home with vulnerable populations — and, how, in turn, human beings suffer when their local ecosystems are destroyed by growling cars. Even setting the obvious threat of roadkill aside, the researchers found that noise levels commonly experienced in redlined neighborhoods can themselves wreak havoc on local animal populations, disturbing their feeding, mating, and migration behaviors and drastically decreasing their numbers over time. Birds are literally forced to sing louder to be heard over the roar of engines; bats struggle to hear their own sonar pulses when they attempt to hunt for food.

And as animal populations dwindle and go silent, their human neighbors suffer, too.

"Abundant research has shown that there's lots of benefits to being exposed to natural and bio-diverse landscapes — and that doesn't have to happen in a national park," explains Sara Bombaci, assistant professor at Colorado State University and the corresponding author of the report. "Some studies have found that even just having exposure to natural soundscapes in informal urban settings can increase human health benefits. ... Especially in marginalized communities, humans are potentially not only experiencing the direct negative health impacts [of noise pollution], but also indirect impacts, like reduced access to the benefits of natural sound."

Despite these clear inequities, Bombaci says urban noise is rarely studied through an intersectional lens. For instance, cities might make moves to increase green space in formerly redlined neighborhoods, but still allow fast, noisy vehicles to travel feet away from parks; towns might put up 'noise cameras' to discourage drivers from modifying their cars for maximum volume, but they may not be accompanied by new tree plantings to buffer sound and increases habitat — and they might not be stationed in the neighborhoods that need them most.

"My best guess is just that noise is not visible," Bombaci adds. "It's something that sort of flies under the radar. You can go into communities and visibly see where there is and isn't green space — but noise is only noticeable only when you're experiencing the worst effects of it."

To more holistically address the impacts of urban noise, Bombaci says cities must explore a wide range of strategies, including reducing vehicle speeds, building "good old-fashioned physical barriers" and sound walls around high-volume areas, and increasing border vegetation and tree lines, in addition to buzzier "smart" approaches like noise-reducing asphalt. It's just as important, though, to recognize that how such things are linked to equity.

"There are certainly scientists that operate from the perspective that, biology is separate from humans and social justice issues," she adds. "I think this is a great example of what happens when you take a social justice lens, and think about how you can improve scientific understanding while also simultaneously challenging some of these systemic injustices."