Noise pollution from busy roads is nearly as harmful to our health as air pollution, according to the World Health Organization — but a new study reveals we're not doing nearly enough research to understand, much less regulate, the sonic impact of cars on our bodies.

A team of Italian researchers found a broad consensus emerge from more than 250 scientific articles: urban noise pollution causes a variety of psychological, cardiovascular, and other health disorders — and the experts estimated that it costs "at least one million healthy life years" per year across Western Europe. Another, earlier study found that residents of Paris and its surrounding suburbs lose an average of “more than three healthy life-years” each to the health impacts of sonic disturbances caused by primarily by cars – something that Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo is tackling head-on with her aggressive 15-minute city campaign to reduce driving.

The researchers didn't consider the specific impact of automobile noise on American ears. But it's pretty clear we're suffering too; only 65.5 percent of Europeans are routinely exposed to traffic noises above 50 decibels, but 97 percent of Americans live with that level of constant ruckus from our car-dominated road network.

Fifty decibels might not sound like much to the average American; it's roughly equivalent the sound of a running dishwasher. But if listening to the sound of a noisy household appliance all day sounds merely annoying, it's important to remember that even low-level noise pollution can be profoundly dangerous — and America's roadways are constant sources of sonic disturbance.

The sound of a car horn, a Harley or pickup with a deliberately loud muffler, or even simply an average sedan doing a legal 40 miles per hour on a nearby road can all activate the "fight or flight" response of our nervous systems, pumping our bodies full of stress hormones that increase our blood pressure, accelerate our heart rates, and weaken our vascular and digestive systems over time. You may not physically even notice it...but it's happening.

Worst of all, continuous noises like these can trigger these hormones even when we sleep, preventing our brains from entering the most restful stages of rest that we need to optimally learn, heal, and regulate our moods — even if the noises aren't loud enough to actually wake us up. The World Health Organization recommends noise levels of no more than 40 decibels outside of our bedrooms, roughly equivalent to the ambient sounds of a hushed library.

Even small discrepancies in sleep can have enormous impacts not only on health, but also on education. In a recent study of college students, teenagers who got a good night's sleep did 25 percent better in academic settings compared to students who didn't — a particularly disturbing discrepancy, considering that people of racial and ethnic minorities, as well as immigrants and non-English speakers, are disproportionately likely to live within 150 meters of a highway.

How loud is too loud?

All-night car traffic is undoubtedly among the most common sources of noise pollution in American cities, but it's impacts are relatively under-studied on a global scale.

The Italian researchers found that 28 percent of the available scientific literature on noise pollution focuses on the impact of air travel — an odd focus, considering that the ill effects of airport noise are relatively well-recognized and well-regulated worldwide. Aviation authorities in most Western nations (including the U.S.) typically require noise abatement measures, including zoning that requires airports to be built far away from residential areas, regulation of flight times to protect residents' sleep schedules, or outfitting aircrafts with noise-dampening technology.

Car sounds, on the other hand, are subject to comparatively little research, and even less regulation. Just 18 percent of studies in the researcher's sample dealt with road traffic sounds — the rest explored wind turbines, rail traffic, and other sources of ambient urban noise.

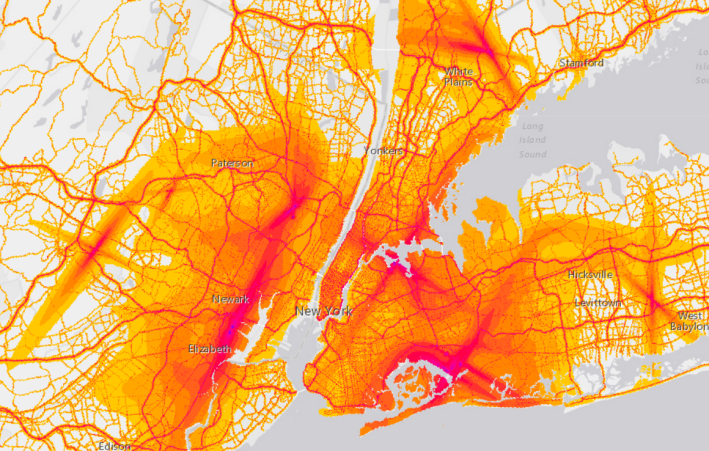

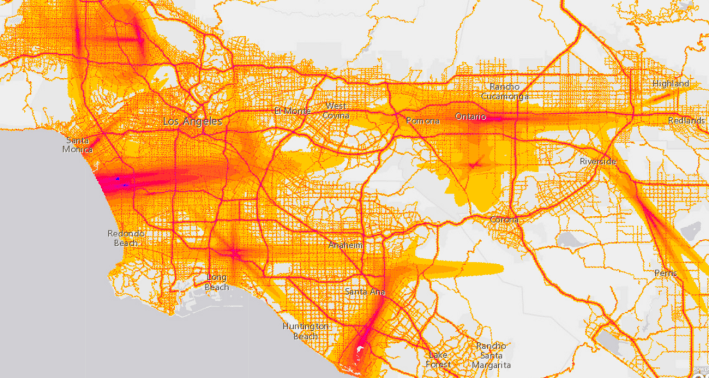

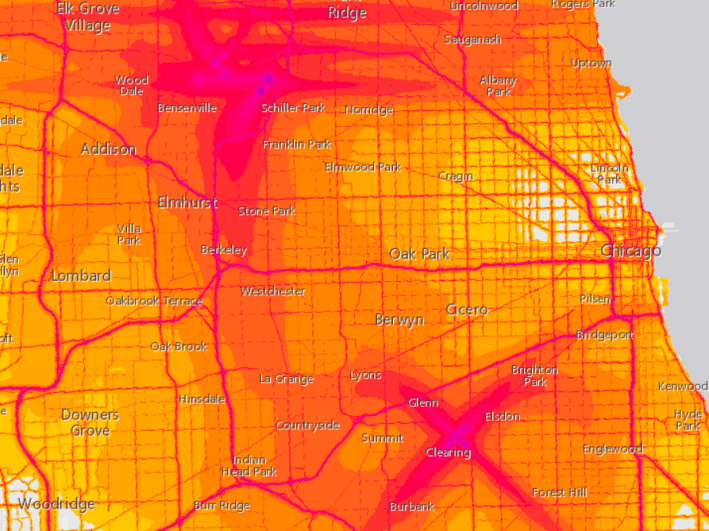

That dearth of research might help explain why restrictions on U.S. roadway sound levels are so lax. The Noise Control Act of 1972 authorized the Environmental Protection Agency to advise states on the recommended limits of noise pollution that would caused by their federally-funded road projects — but the responsibility for actually setting noise caps was shifted to the states less than ten years later, when the funding for the federal Office of Noise Abatement was rescinded. Absent that money, states had little incentive to set high standards that would quiet roadways down — and so, as the National Noise Map shows, most of them simply didn't.

Locally, noise abatement is an even lower priority. The New York City Department of Health and Mental Health, which is seen as a model agency for cities and even for federal authorities, has long refused to answer any questions from Streetsblog NYC about how it plans to address the mental health toll of excessive noise related to car travel.

Today, states and municipalities face virtually no federal consequences for failing to protect their residents from toxic levels of noise — and even the non-binding guidelines the feds do offer are far too weak. The Federal Highway Administration actually noted in a recent report that a neighborhood where roadways cause interior noise levels over 55 decibels in surrounding buildings would be a good candidate for noise abatement — despite the fact that the EPA acknowledged that constant noise in excess of 45 decibels could damage human health way back in 1974.

Why we can't quiet the cars

If the national government's stance on appropriate roadway noise levels are toothless, it should come as no surprise that the funding it gives states to actually mitigate the pollution is pretty thin.

The Federal Highway Administration provides almost no funding for highway noise abatement when it funds new road-building projects, besides a small number of federal dollars for concrete "noise walls," which don't really work. Some advocates have argued that a federally funded shift to electric vehicles, which don't have noisy internal combustion engines, could help drivers pipe down, too — but of course, that won't happen if Trump is re-elected. And because tire and wind noise, not engines, is actually responsible for most roadway noise when cars travel over about 20 miles per hour, it wouldn't help much anyway in America's perennially too-fast cities.

And when they're traveling under 20 miles per hour, electric vehicles are actually so quiet that they become dangerous to human health in another way: pedestrians can't hear them approaching. Effective this month, all new EVs will be required to produce a fake roadway sound to protect walkers from low-speed crashes — though since automakers like Tesla's Elon Musk are reportedly considering letting drivers choose their own alert sounds, including fart noises and goat bleats, it, uh, remains to be seen how much that will actually make cities more peaceful.

Of course, there's a simple way to quiet down American streets: limit car travel as much as possible within aural reach of areas where people live, work, play, and learn. (Again, the New York City Department of Health won't discuss that topic.)

But until we have a major transportation revolution towards biking, walking, and comparatively quiet transit options, the burden will fall on the average American to protect herself from yet another pervasive public health threat inherent to the automobile.

The good news? At least you can get a decent white noise machine for about $40.