From one standpoint, U.S. micromobility is having a major moment.

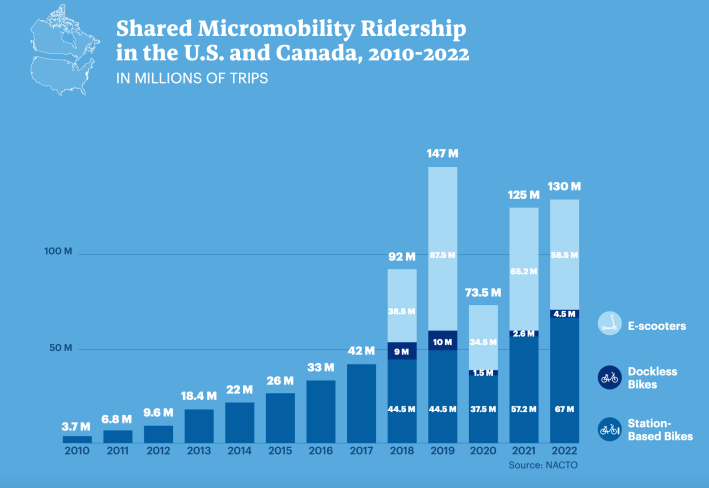

NACTO’s recently published annual micromobility report showed that docked bikeshare just had its best year in history, roaring back from pandemic-era lows and eclipsing last year’s record-setting trip numbers with reported 71.5 million journeys across U.S. and Canada in 2022. Dockless bike and scooter-share, meanwhile, is being praised for finally "growing up" from its "Wild West" days of dumping fleets onto city streets overnight and into mature partnerships with municipalities, which increasingly view their product as an essential component of the sustainable transportation ecosystem.

Meanwhile, the wider universe of human-scaled mobility won a general vote of confidence in September, when the U.S. Consumer Protect Safety Commission confirmed that deaths involving e-bikes and e-scooters are exceedingly rare: just 111 between 2017 and 2022 — only 10 of which involved a pedestrian. (Overall car crash deaths during that period, for contrast, topped 235,000, and over 40,000 of them were walkers.) Moreover, shared bikes and scooters consistently reported lower rates of injuries than individually owned ones.

That tidal wave of good news, though, is being met with an equally-massive tidal wave of uncertainty.

While docked bikeshare ridership soars, the single largest operator of those systems — app-taxi giant Lyft — is reportedly looking to unload its entire fleet anyway, despite big, simultaneous investments into e-bikes in cities like New York. Elsewhere, whole bikeshare networks in Louisville, Houston, Minneapolis (which was also operated by Lyft), and others have shut down amid financial uncertainty, only for some to be thrown lifelines by their city councils and dockless micromobility companies.

But that doesn't mean the dockless companies aren't facing stormy waters of their own. Over the last year, the industry has been roiled by news of mergers, citywide pullbacks, and a 10-percent drop in scooter ridership between 2021 and 2022, the latter of which NACTO blamed partially on "financial struggles" and "shift[s] in company-wide operating priorities," as well as increases in ride prices that outpaced docked modes.

So which is it? Is U.S. micromobility industry on the brink of a breakthrough? Or is the bottom about to drop out?

To subsidize or not to subsidize

At the heart of that question lies a deep anxiety about the structural foundations of the micromobility industry, and whether those foundations are beginning to shift. Most American cities have expected micromobility to operate without public subsidies that other forms of transit enjoy, with some outfits even being charged to provide residents with a convenient alternative to driving — something transportation writer David Zipper called bikeshare's "original sin” (though it could just as easily describe scooter-share, too).

That split has typically fallen along modal lines. Docked bikeshare systems, like Capital Bikeshare in Washington, D.C., tend to be the result of public-private partnerships with strictly negotiated terms, with cities either owning the system outright and contracting with a private operator to run it, or allowing private businesses to run systems with city permission, usually for free or receiving a subsidy in the form of discounting residents' rides or some investment in the fleet. The private companies that run dockless systems, meanwhile, virtually all own their own fleets, and are usually charged fees to run on public streets, while still being held subject to strict terms.

That discrepancy isn't universal; for instance, the operators of Chicago's docked bikeshare program, Divvy, are required by contract to pay millions to the city every year. (Editor's note: In New York, Lyft pays the city for "lost" parking). But in some ways, treating docked and dockless operators differently makes a kind of intuitive sense. Maintaining stations in addition to bikes costs more, and ripping them out is expensive too; dockless operators, meanwhile, can drop or collect fleets overnight depending on whether a given market makes sense for their bottom line. And in the early days of the industry, they often made those moves aggressively; back in 2017, many scooter companies were led by alumni of Silicon Valley "disruptors" like Uber, and according to transportation writer Ali Griswold, they borrowed heavily from those companies' playbook of "ask forgiveness rather than permission" when they made the shift to two wheels. That included — and in some cities, still includes — failing to get their vehicles off sidewalks and out of the paths of wheelchair users, leaving some cities

"A lot of people in the scooter and the micromobility space will tell you that they feel sort of unfairly maligned, over-regulated, overburdened by the rules cities have implemented, as well as the fees, the infrastructure requirements, all these sorts of things," Griswold wrote. "But I think if you're looking at it holistically, all of that is a product of this ill-will that was created during the Uber era, which [spilled over into] the early micromobility era."

'What do you want micromobility to be?'

Griswold said, though, that a lot has changed in the years since the scooter industry was born, and that management turnover at both Bird and Lime has brought with it deeper and more stable collaborations with cities.

And it's happening just as the cracks in America's docked model are starting show. It's not clear why Lyft is pulling back from bikeshare at the exact moment the mode is breaking records, but statements from its CEO suggest to Griswold that for the ride-hail giant, "owning ... bike-share systems isn’t about enriching urban transport or closing the last-mile gap with more sustainable modes; it’s an elaborate marketing campaign to install the Lyft app onto more phones and get more passengers into its cars" — and that now that it's clear gambit is "not paying off," it wants out.

Other docked systems, meanwhile, have simply run out of money to keep up with the costs of servicing a vast network of stations, even when operated by non-profits with no obligation to shareholders. Non-profit-led B-Cycle in Houston, for instance, struggled to land a title sponsor even as ridership soared during quarantine, sending the system into a spiral of maintenance challenges as fleets grew increasingly worn out and essentially making the network a victim of its own success. In an interview with Mass Transit magazine, board Vice Chair James Llamas even said that "it makes a whole lot of sense for public bike share to be run as public transit," given that user revenue only ever covered 60 percent of B-Cycle's costs, and sponsorships didn't cover the gap.

But not everyone agrees that bringing micromobility under the transit umbrella is always a good idea. If you somehow haven't heard, U.S. public transit agencies aren't doing too hot in the wake of the pandemic, with revenues in many cities still in the toilet and subsidies to cover the gap still hotly contested in Congress, not to mention states and municipalities. If holding the bike- and scooter-share universe captive to the whims of private shareholders feels inherently unstable, some micromobility leaders argue that holding it captive to the whims of transit-hostile U.S. governments is unstable, too — and while they say those governments shouldn't charge micromobility companies to operate on their roads, lest they be forced to pass those costs along to riders, governments also shouldn't necessarily be counted on to keep fleets running.

"While we are not opposed to subsidies, we don't seek them," said Josh Meltzer, head of Government Relations for North America at Lime. "Instead, cities should align policy in ways that nurture the growth of car-alternatives and incentivize their use over driving. ... Ultimately, cities should avoid charging fees to dockless scooter and bike providers running a service at no cost to taxpayers and providing well-documented sustainability and equity benefits, all while reducing the high externality costs to cities associated with pervasive driving over time."

For Griswold, the question of what it will take to make micromobility stable and successful doesn't have easy answers. And if anything, it provokes even more difficult questions.

"From a philosophical point of view, there is a question of: what do you want bikeshare and similar micromobility programs to be?" she said. "Do you want them to be an extension of public transit? Do you want them to be sort of a supplemental, private, for-hire service, more like an Uber? The way that you structure and finance these programs, I think, will necessarily will shape the outcome that you get."