Residents of New Jersey would reduce their yearly rent by $1,056 on average if their leaders would simply relax outdated rules that require developers to build car storage that many residents aren't even using.

In a new study from the Rutgers Center for Real Estate, researchers found that Garden State renters, on average, "own fewer cars per unit than developers are required to provide" — specifically, about one extra space for every two units — and that by simply aligning those requirements with the number of vehicles residents actually have, New Jersey could bring average rents down by about four percent, or $88 a month off a typical $2,200 unit built after 2010.

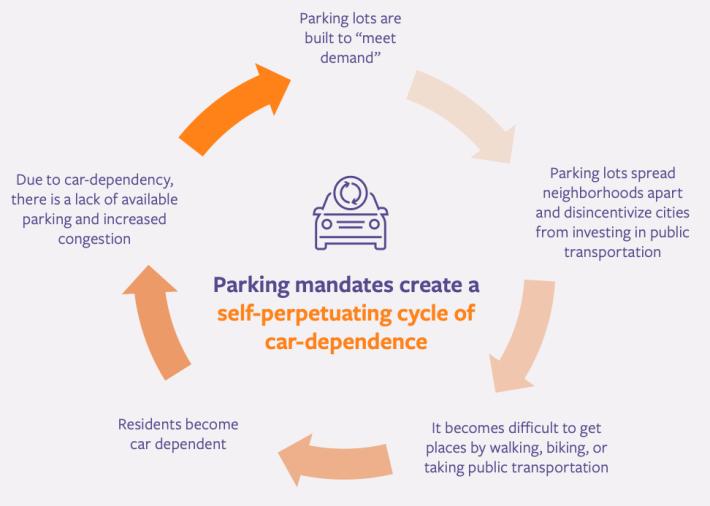

That might not sound like much, but it's the tip of the iceberg. According to the Parking Reform Network, other studies have found that eliminating all parking requirements can decrease rents and mortgages by $200 to $500 a month, depending on how and where those spots are built. (A recent white paper from Streetsblog's parent organization Open Plans cited research that estimated the costs of parking garages alone increase rents on adjacent buildings in New York City by roughly 17 percent). And that's not to mention all the other environmental costs of coating the earth in concrete, like exacerbating urban heat islands, altering stormwater runoff patterns, and encouraging car dependency.

"This parking 'issue' comes up all the time in site plan apps," said Debra Tantleff, co-author of the study. "But the reality, is the world has changed; the cost of building parking has changed; and the costs of parking, in terms of environment are more clear than ever."

Tantleff points out that even a four percent drop in rents would "actually [be] a pretty significant annual escalation factor," considering it doesn't account for natural inflation or natural increases in the housing supply should standalone lots and garages be supplanted with new apartment buildings. And it also doesn't account for increases in transit, walking and biking infrastructure that might make all those empty spots even more superfluous as residents ditch their cars for other modes.

That doesn't mean, of course, that relaxing parking minimums will be politically easy. New Jersey, like many U.S. states, gives municipalities the power to set local zoning codes as long as they comply with overarching state laws. As a result, Tantleff says excessive parking mandates are treated as a "very personal community issue" in New Jersey, rather than an outdated policy that a mountain of international research has shown to be actively harmful.

If research like this can penetrate the public consciousness, though, Tantleff is optimistic that New Jersey can win its ongoing fight to curb concrete construction, and join the growing legion of U.S. communities that are winning similar battles.

"New Jersey is one of the toughest states to do what we do," she added. "If we can succeed in recognizing the impact of parking minimums here, we can do it anywhere."