Many sustainable transportation advocates fear that the era of autonomous vehicles will spur us to even further optimize our streets for the efficient operation of machines rather than the cultivation of experiences that make us fully human. By adopting a framework that radically centers 'livability' on our roads, though, could we make the robo-cars work for us — and maybe, undo the damage of the first wave of automobobility?

On this episode of "The Brake," Kea Wilson sits down with author Dr. Bruce Appleyard to talk about his new paper, "Designing for street livability in the era of driverless cars," as well as his book, Liveable Streets 2.0, and the the legacy of his father, Dr. Donald Appleyard, who wrote the original edition. And along the way, we talk about why "livability" is about so much more than safety and the difference between "designing" and "programming" our places to prioritize our humanity.

The following excerpt has been edited for clarity and length.

Kea Wilson: Generally speaking, what was the genesis of this fascinating study?

Bruce Appleyard: The genesis was there was a lot of discussion about the rise of autonomous vehicles and people were getting very excited about autonomous vehicles and what they could promise and how they could reshape the world.

And I am a natural skeptic about auto-mobility and how it actually affects our lives. I do see the benefits of autonomous vehicle technology and making things safer, but I also would say, "Why don't we just adopt those things into our everyday vehicles now?" — such as speed governors to slow cars down and early detection warnings that also make them better able to detect pedestrians and bicyclists.

And I wanted us to examine and then lay out actually a manifesto there. And to lay out what things specifically we should be thinking about with regards to the design of the of the vehicles, the design of the streets and also the design of our regions.

KW: So before we get into that manifesto, which I think is really important, I think we should just frame the risks, frame the problem. When you and the experts whose work you reviewed for this paper, think about the worst case scenario for the AV future, what do you picture?

BA: Well, I think there are a couple of things that are gonna happen or potentially happen now and, but I do want to say, first of all, autonomous vehicles could in some ways be safer, they could be smaller, they could be urban friendly. If they're not smaller, that's not gonna help. And if they don't have the ability to detect other vehicles and people and bicyclists, they're not really going to help that much either.

And if they really encourage much more driving, there are several things that are gonna happen. One is we're gonna have many more cars on the roads. It will become more congested under any scenario, even the most optimistic sharing scenario of sharing of cars and vehicles. Taking away the cost of driving is just going to increase driving and encourage people to drive further distances.

And there should be good regional land-use controls to make sure we don't sprawl out of our minds because we now have vehicles that will drive us without living the cost to drive. And what we also see from other studies about autonomous vehicles is that people probably aren't going to pay for the parking of the vehicle, but they're actually gonna continuously cruise.

So in high activity areas, we're likely to see a fleet of cars circling continuously, possibly in low-income neighborhoods of color near downtowns. And so that's gonna be become its own impact. So a lot of the benefits that people are promising about autonomous vehicles may not actually come true.

And so we wrote this article to talk about specifically how you should think about designing the vehicles, designing the systems, making sure that you're doing a good job in terms of information sharing, that you're actually taking advantage of handheld devices to reward people for doing such things as bicycling and walking and taking transit as opposed to just driving. And that we also design the streets so that you could potentially take back some right of way. If you're actually able to encourage people to drive in autonomous vehicles, you could potentially make them smaller and narrower and take up less of the road.

These vehicles don't need as much lane space. But if all we're doing is making it easier to drive and encouraging more driving, we're not gonna really realize that those potential benefits of autonomous vehicles.

KW: Let's talk about the three principles that you outlined in this paper. Let's start with the third one: productively designed and program streets for beautification, liability and humanity. So since you literally wrote the book on it, I have to ask what is a livable street in the era of the AV, and what do you mean about not just designing them, but programming them for human thriving? And then how does that flow into these other ideas of beautification and humanity that you introduce here?

BA: So my father, yes, he wrote the original book, Livable Streets. And it was the first book that really showed people the damaging effects that cars had on communities and social ties and on streets. And especially with regards to street livability. He was referring to people who were residents along streets. And so his idea of livability was that it was a peaceful, restful rejuvenating place.

I expanded it to talk as well about bicyclists and pedestrians and how to make sure that the the auto-domination of neighborhoods didn't really take over pedestrians and bicyclists and how it could actually designed to make things safer for pedestrians and bikes as well. Liability is also a level of not just safety but also comfort. It's how are you being cradled by your environment and encouraged by your environment to, to be at ease, at peace and in a rest restful rejuvenating state.

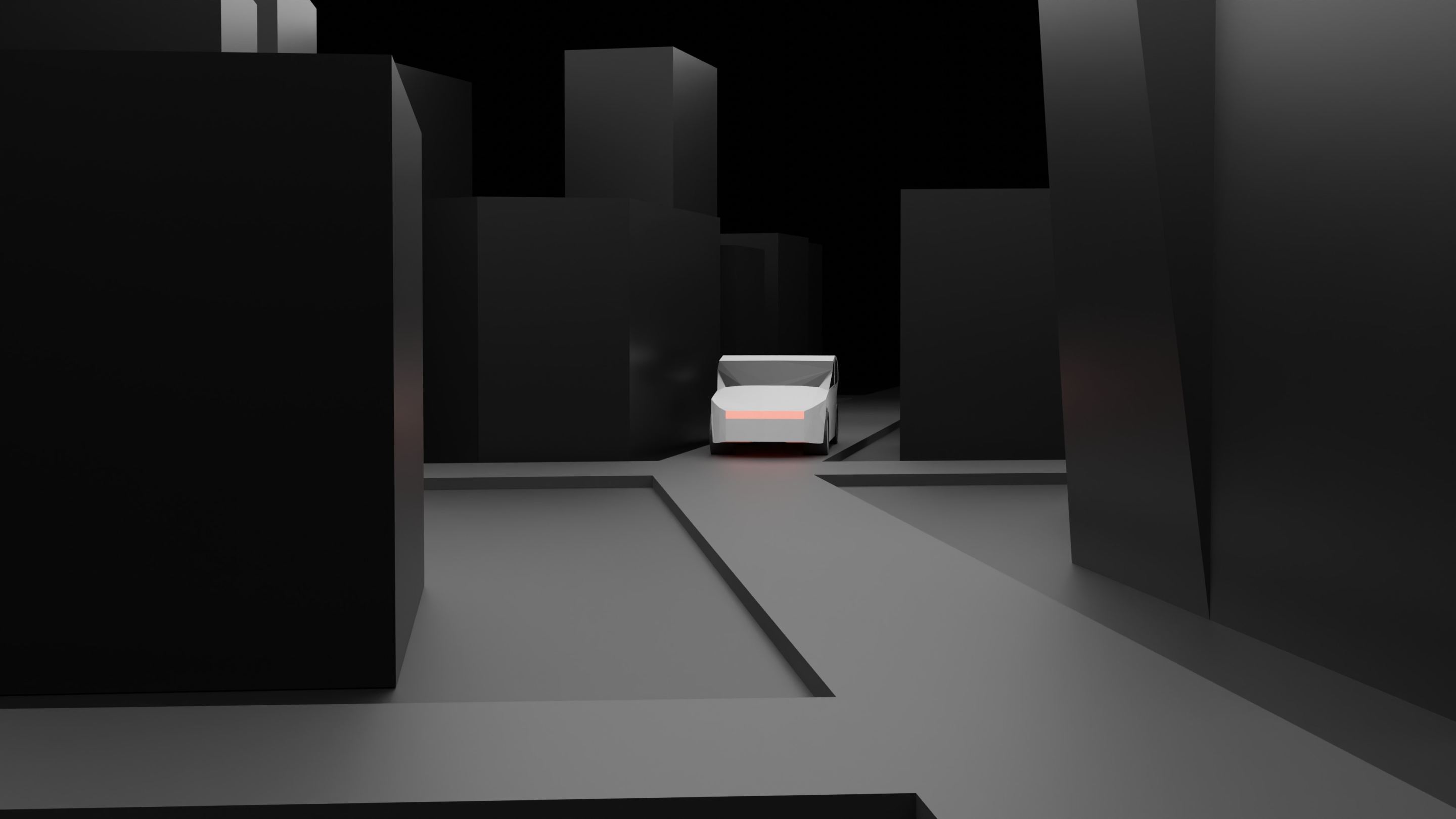

So the idea that we tackled in our article was to say, what are the things we need to do to make sure that this future of autonomous vehicles maintains not just the street livability, but also our humanity. As I started to look at the writings about autonomous vehicles and the type of world they could create that it could potentially feel like living in a watch and sort of a diminished sense of your humanity could take place if you feel like you're living inside of a machine.

And I think that we need to make sure that in every way possible that we design the vehicles and the streets and program the streets and the vehicles to make sure that streets are, as my father said, for people. And I argue in Livable Streets 2.0 that streets are for our humanity and that we need to make sure we're very mindful and deliberate in how we go forward to make sure that we maintain both our street livability and our street humanity.