Low-income people are using shared micromobility a lot like they use public transit, a new study finds — and researchers think cities should thoroughly embrace (and subsidize) the mode as part of the larger ecosystem of buses and trains.

Researchers at Monash University, using survey data from micromobility giant Lime users across all income levels in the U.S., Australia, and New Zealand, dug deeper into how low-income people uniquely use the company’s vehicles.

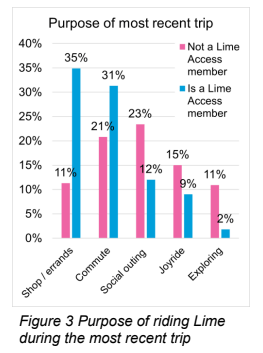

Participants in the Lime Access program, which grants discounts of around “70 or 80 percent” to riders who qualify, were significantly more likely to list essential reasons like “shopping” for groceries (35 percent) and “commuting” (31 percent) than non-Access riders, 11 and 21 percent of whom rode to complete errands or go to work, respectively.

The discount recipients were also highly unlikely to go use bikes and scooters for non-essential reasons like social outings (12 percent), “joy-riding” (9 percent) or exploring (2 percent), quashing the stereotype that all micromobility trips are spontaneously generated. And a whopping 44 perccent of their trips connected to a traditional transit ride, compared to just 23 percent of people who paid full price.ago

Perhaps the most surprising findings, though, were riders’ qualitative responses about what micromobility meant to them, and how their lives were made better by having access to affordable ways to get around without a car. Calvin Thigpen — director of policy research for Lime and co-author of the report — says he was particularly moved by the number of riders with invisible disabilities who said Lime Access helped them get where they needed to go, even when local transit schedules didn’t meet their needs.

“Something that really shone through in some of these quotes … was how much people really needed this program, and really came to rely on it,” said Thigpen. “It’s easy for people to think of Lime and other shared scooter options like they’re just toys that people just use for fun. And that’s just really not the case. People are using this to get around for pivotal trips; they are heavy, often daily users.”

About 62 percent of cities with micromobility programs today require operators to meet at least one equity requirement in order to run fleets, and discount programs like Lime Access have become an increasingly popular way for them to do it; in Chicago alone, Lime has offered roughly 400,000 discounted rides so far this year, and saved participants a staggering $1.1 million.

And according to the new analysis, all that money is buying something valuable: better daily mobility for the people who are least likely to own private cars.

Those inspiring benefits, though, come at a cost that micromobility companies’ razor-thin margins can’t always afford. Houston’s B-Cycle and Minneapolis’s Nice Ride are just a few of the prominent bikeshare outfits to shut down in the wake of recent financial difficulties, and the researchers say the entire micromobility industry is grappling with “potentially existential risks to [their] ongoing operations” while working to expand access to the riders who rely on them most.

The roughly $7 million that Lime handed out in equity-focused discounts in 2022 didn’t stop the company from achieving its first full profitable year. But Thigpen said the company could do a lot more for low-income Americans if cities simply recognized the impact shared micromobility has on their lives — and treated it as an important component of the transit universe.

“I think that’s something that would be very valuable,” Thigpen added. “It’s something that transit agencies already do when they contract out to private bus operators, or even private train operators. This would not be some novel thing; it will just be a new mode, being integrated into transit. … At the end of the day that’s really our goal, right? Our mission is to achieve a future of transportation that’s shared, affordable, and sustainable; I think [making micromobility] a bigger part of transit is a really, really valuable approach.”

What the transitification of micromobility might look like

Enhancing public support for scooter and bikeshare, Thigpen stressed, can take many forms. Cities like Denver have completely waived program fees for micromobility operators in exchange for them meeting robust equity benchmarks and building parking corrals to keep scooters off sidewalks, while others, like Washington, D.C., offers them scaled refunds on that fee based on how what percentage of miles low-income riders travel compared to the overall rider pool.

He also suggests that the growing list of U.S. cities offering residents rebates to buy their own e-bikes could expand their programs to offer e-bikeshare memberships to low-income riders — particularly for people who have no secure, convenient place to store an e-cycle of their own, don’t want to lug a heavy e-scooter up a set of apartment stairs, or can’t afford the expense of fixing an e-vehicle when it breaks.

“It seems like every city and state is getting on board with e-bike rebates these days,” Thigpen added. “And I think it’s worth asking the question: Are they meeting the needs of everyone, and is there a space for shared programs [to participate]? Could [offering shared e-mobility memberships] meet the needs of lower income riders, disabled riders, people who live in places where they can’t securely lock up a vehicle? That’s my speculation, but it’s definitely worth further study.”

Thigpen acknowledged that cost is far from the only barrier to micromobilty that low-income riders face, and that Lime and cities can do more to help.

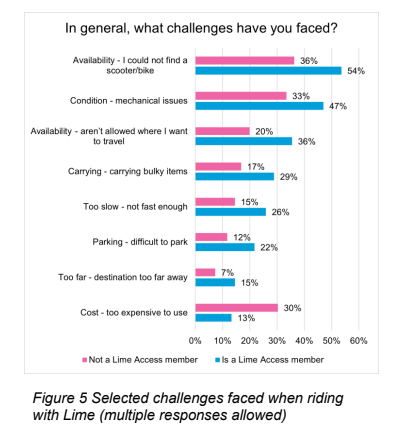

Most Access riders (54 percent) reported frustration with not being able to find a vehicle when they needed it, suggesting that cities may need to relax fleet caps, and that operators may need to do a better job of reshuffling bikes and scooters into the neighborhoods where people need them most. More than a third of them (36 percent) said that they couldn’t always take micromobility to the places they needed to go, thanks to slow- and no-ride zones that automatically throttle vehicle speeds when they passed invisible digital borders called “geofences.”

And 75 percent of Lime riders had never even heard of Access, including some who qualified for the program, but hadn’t signed up. Others struggled to sign up — something the company says it’s addressing with targeted awareness campaigns through companies like Propel and a newly streamlined, “near-instantaneous” application process. (The researchers didn’t ask about whether fear of traffic violence or lack of bike lanes were significant barriers for Access riders, but other analysis has found that’s definitely a factor for would-be micromobility users on the whole.)

However cities move forward, Thigpen stressed that it’s critical that they continue to study how micromobility can work for residents who are poor, living with mobility challenges, or simply sick and tired of waiting for buses that never come.

“Lime is are essentially another transit option,” he added. “We’re not a bus; we are not a train. But people use us in the same fashion that you would a bus or a train.”

Editor's note: an earlier version of this story mis-stated the number of discounted rides Lime offered in Chicago. We regret the error.