America’s national electric vehicle charging effort is leaving out the types of EVs with the most potential to curb catastrophic climate change: the shared electric bicycles and scooters that are ideal for short trips in our cities and towns, advocates say.

According to a new report from the North American Bikeshare and Scootershare Association, the federal government currently dedicates zero dollars to on-street docking stations for e-bikes and other micromobility options — or, more accurately, human-scaled modes — compared to a staggering $7.5 billion for shared and private electric cars.

And that omission, the report authors argue, is slowing the rollout of a critical mobility alternative without which we’re unlikely to curb the worst effects of climate change. Climate experts say that global city-dwellers must use a mode other that driving for at least 40 percent of the miles they travel by 2030 to keep transportation sector emissions under control, but Americans often rely on private cars and cabs even for short, safe journeys that many Americans could accomplish by e-bike — if there were only one around.

“In order to scale the benefits of shared micromobility and support the growing demand, it is essential to develop connections to the electrical grid and implement electric shared micromobility charging stations,” the authors wrote. “Funding and support at all levels of government [are] critical to making this happen.”

Whether they’re being ridden by people with disabilities or folks who just don’t want to get sweaty, electric vehicles are rapidly coming to dominate the shared micromobility universe, with 55 percent of systems reporting at least some battery-powered vehicles in their ranks in 2022 (up from just 28 percent in 2019). The same year, 65 percent of all shared bike and scooter trips involved some kind of an electric boost, and 37 percent of journeys replaced a car trip, offsetting a whopping 74 million pounds of carbon dioxide.

To keep those fleets running, though, operators are often forced to pull vehicles or their batteries off the streets and charge them in warehouses, increasing labor and transport costs so much that it’s all but assured that e-vehicles will never be “viable at large scale.”

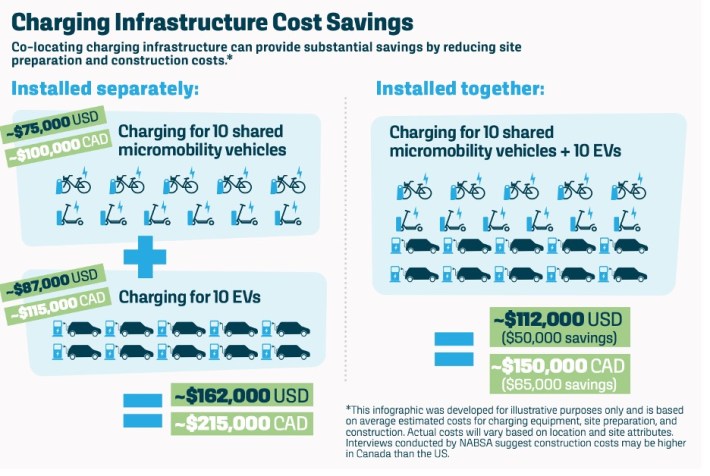

Charging small vehicles in the field, though, also isn’t very cost efficient — at least without up-front government help. Connecting a scooter or bike dock to electricity in the field requires intensive site preparation like digging trenches, or installing solar panels that the report authors say represent “substantial additional cost to the charging station itself,” even if that panel eventually delivers power back to the grid.

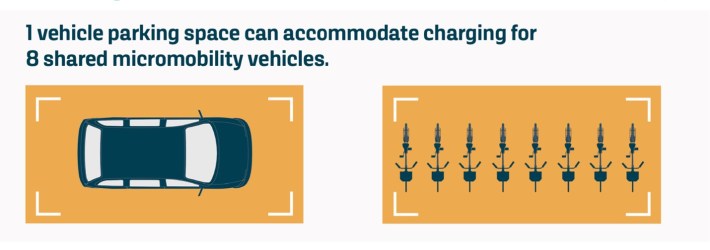

Building charging stations for electric cars, of course, isn’t cheap or simple, either — and they don’t deliver nearly as much environmental bang for cities’ buck, considering that a single-occupancy electric Ford F-150 uses way more raw battery materials to move the same number of people as a scooter. Under federal law, though, every U.S. state is required to submit a statewide EV charging plan — and besides the state of Oregon, none has included micromobility in those plans.

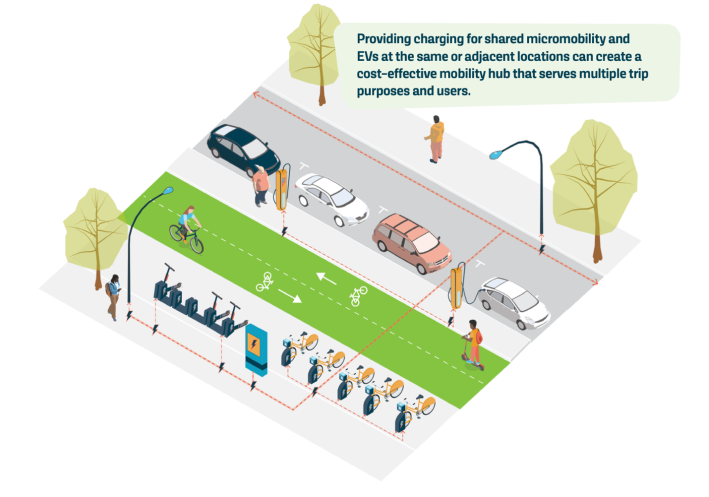

Ironically, those same car-dominated EV charging plans could help U.S. communities create the blueprint for building networks of micromobility charging infrastructure, too — if they have the foresight to install them when they’ve already dug up their streets. And even if cities don’t have the money to put up bikeshare docks right now, they can at least ready the grid for those improvements later, especially in underserved communities where micromobility might have the most impact.

The North American Bikeshare and Scootershare Association stresses that transportation leaders at all level of government are responsible for making sure the EV charging revolution doesn’t leave the micromobility industry behind. Federal policymakers can and should create dedicated funding sources just for bike and scootershare charging, but states can already leverage the Carbon Reduction Program and local politicians can open up their land use codes to incentivize or even require certain developers to invest in emerging green modes. Developers, meanwhile, can take advantage of the Alternative Fuel Vehicle Refueling Property Credit to build docks on their land — universities and properties near transit are particularly prime candidates — and utility companies can make creating grid connections suitable for charging stations a routine part of their operations.

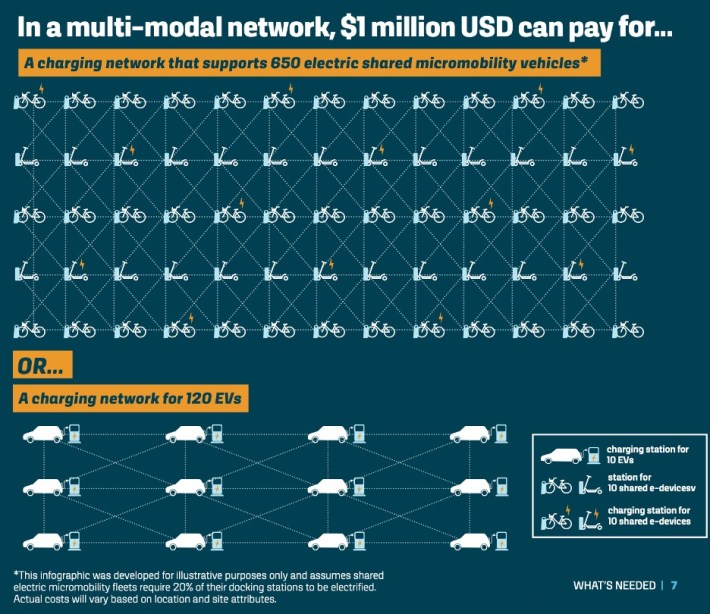

Since only an estimated 20 to 30 percent of all micromobility hubs need to be electrified to adequately serve the charging needs of most operators, the report authors are confident that U.S. communities can rise to this challenge — because if they don’t, we’ll miss out of a once-in-a-generation opportunity reduce car dependency.

“This is an important moment and opportunity for policymakers and civic partners to think and act multimodally and holistically across policy and implementation,” NABSA wrote.