Online grocery delivery service — once hailed for its potential to reduce emissions and driving — may actually increase both in some circumstances, a new study finds.

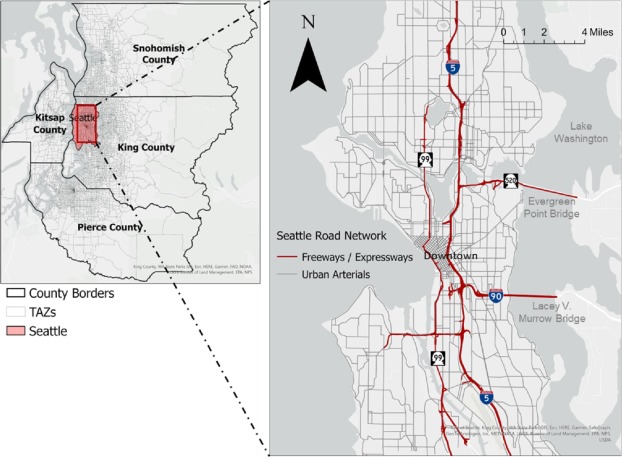

In a recent paper published in Transportation Research, analysts at Carnegie Mellon used household travel data from Seattle to model how congestion, emissions, and driving patterns would change if more residents shifted from doing grocery shopping themselves to using a service like Instacart, Amazon Fresh, or Walmart+ to do it for them.

Though the concept of getting food brought straight to your door has existed for well over a century, today’s legions of lanyard-wearing gig economy workers are a far cry from the milkmen on horse-drawn carriages of yesteryear, particularly as online services surged in popularity during the pandemic. The researchers say that the virtual grocery biz increased its market share sixfold between August 2019 and June 2020, and that researchers “believe this shift in demand for online groceries will continue to grow after the pandemic subsides.”

The impact of that potential shift, though, has gone largely unexamined by city governments — and whether it will match up with city priorities like reducing car travel isn’t clear.

“We were wondering; is it really more efficient to have a centralized system where Amazon or Uber Eats or someone else is delivering our groceries?” said Corey Harper, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering and the co-author of the paper. “Or is it better to have everyone doing their own thing? How does human behavior affect this? If delivery is free, will people get groceries three times a week instead of once? If I want to bake a pie and I don’t have cinnamon, will I just order it by itself from Amazon instead of waiting for my next trip to the store, and create a vehicle trip that wouldn’t have otherwise occurred?”

Harper and his colleagues didn’t assume that grocery delivery schemes would surely slash the number cars on the road just because a truck is theoretically capable of servicing multiple homes in one go, saving each resident from having to make a separate trip. Unlike some previous research on the topic, they also didn’t assume that residents would always shop at the market around the corner rather than the specialty co-op that sells that one kind of bread they like across town, or that small, locally owned groceries in neighborhoods would even have the resources to support a crew of in-house delivery workers, or be willing to list themselves on a gig economy platform. They even modeled how the time of day that customers places their online orders might impact local travel outcomes, the proliferation of electric vehicles throughout the delivery fleet, and whether customers would replace a weekly, in-person supply run with an identical online order, or just complement an in-person trip with a flurry of one-off shipments for a handful of items.

And perhaps most important, they didn’t assume that Seattleites made dedicated trips to the grocery store and back without stopping anywhere else, rather than tacking a grocery run onto the journey home from work, school, or another destination.

With that dizzying array of variables in mind, the researchers found that grocery delivery wasn’t necessarily a slam dunk for reducing emissions or the number of cars on the road. Some of the scenarios produced by the model reported potential peak-hour CO2 reductions of as much as 0.9 percent, while others reported increases in emissions of as much as 4.9 percent. Vehicle hours traveled, meanwhile, could dip as much as 4.2 percent … or increase as much as 6.3 percent, depending on the specifics how people shop.

To make grocery delivery live up to its true potential and not make U.S. streets more polluted, congested and car-dominated, the study authors recommended that governments and grocery stores work together to incentivize consumers to at least order their goods from the closest supermarket, as well as imposing higher fees on frivolous shipments of, say, single jars of cinnamon, and lower ones on a complete week’s worth of food. They might also use discounts to incentivize customers to accept grocery deliveries outside of peak travel hours, rather than guaranteeing that they’ll get their goods in under an hour even if the streets are snarled with cars.

And while the study authors didn’t focus heavily on car-free solutions to the grocery delivery problem — think hiring bike deliveristas and building the infrastructure to keep them safe, transit-oriented supermarkets, and great zoning and community development policies that put walkable mini-markets on every corner — they did have one piece of VMT-reducing advice for U.S. shoppers.

“Grocery delivery has its place, and I think there are ways to encourage better uses of it,” added Harper. “But if you can buy your own groceries on your way home, then yes, you should definitely do that.”

The post Grocery Delivery May Not Reduce Driving As Proponents Claim, Data Show appeared first on Streetsblog USA.

The post Grocery Delivery May Not Reduce Driving As Proponents Claim, Data Show appeared first on Streetsblog New York City.