A version of this article originally appeared on Exasperated Infrastructures. It is republished with permission.

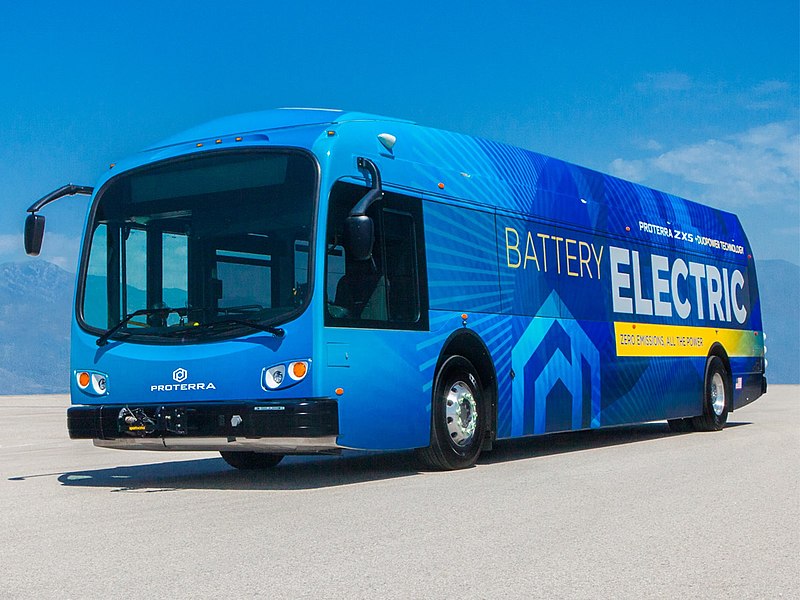

Depending on your perspective — and how bullish you are on the future of electric mobility — Proterra’s heavily-PRed bankruptcy filing was some combination of expected, concerning, and forethoughtful. Because even without the largest American EV-bus manufacturer folding, replacing entire fleets of diesel buses with battery-electric powered ones will be hard enough.

The first reason is scale. Conservatively, there are tens of thousands of buses in operation in the US, a tiny portion of which are already battery-electric, and a huge portion of which need to be battery-electric in the next 10-20 years. As comparatively large as it is, Proterra still only delivered 1,300 buses between 2004 and 2023. It would seem that sheer capacity has made us insatiably hungry for this equipment.

Second: policy. For better or worse, we’re bound by strict rules that compel transit agencies to buy American-made buses and corresponding parts. I’m not sure that Proterra will completely exit the market — and even still, it’s not like the processes, property, plants and equipment they’ve already built would just disappear. But obviously, unless we loosen Buy America provisions or incentivize a boom in massive chassis original equipment manufacturers in this country through policy, we’re going nowhere.

Third: funding. The United States on the whole already has (or at least can generate) enough purchasing power to buy the buses we need. Individual agencies, bleeding uncontrollably, cannot — even the big ones. In addition to strong policies, we have to put our money where our mouths are. If we really want to hit our climate goals — or other goals — we just have to pay for it, and signal that we will.

Fourth: complicated Catch-22s. Beyond electric buses themselves, we have to make sure that we have operational buses during the transition. In operations and inventory management, we might look to first-in/first-out or last-in/first-out scenarios, but really, it’s way more complicated than that. The average “lifespan” for a new diesel bus is about twelve years, and each bus is fully dismembered and restituted about halfway through its life. Transit agencies still run buses from brand new through way past a bus’s expected revenue-life for all the reasons we've listed here. It’s not going to be a one-to-one replacement of old vs. new.

And even if it were a one-to-one replacement, there are still logistical challenges that are going to take a long time to solve. The biggest of which is range: where a diesel bus could make a journey of x number of miles before, now it can make something like x-10 miles or x-20 miles. This alters not only the populations a single bus can serve, but also how bus routes interact with one another, and where and how often the buses have to recharge and redeploy. Where do they do that? How do hiring patterns change? Are any of these buses going to also be autonomous or semi-autonomous?

Even if these logistics have been worked out — and they will be by some our finest minds working in partnership —we still have to figure out the ancillary charging infrastructure and where we’re sourcing the energy from. If we’re still burning coal or oil to power the generators or to fill the batteries that will run our buses, we’ll be making no progress at all.

Sam Sklar is a planner and the author of Exasperated Infrastructures.