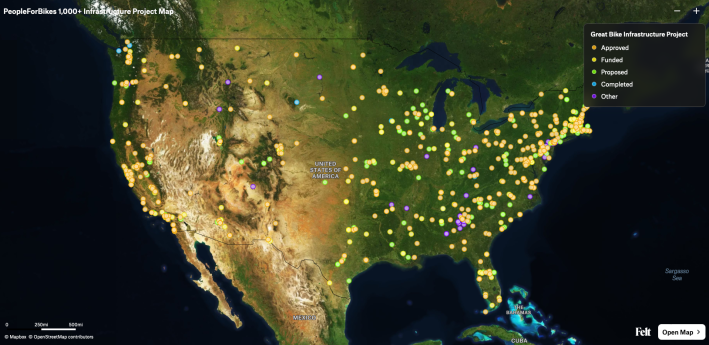

A new tool will help U.S. advocates fight for a national bike infrastructure network with the same passion with which highway boosters once fought for the national interstate system — and find battles close to home where they can have the most impact.

Nonprofit PeopleForBikes' recently launched the Great Bike Infrastructure Project, a new advocacy portal which aims to map all the "protected bike lanes, off-street trails, pump tracks, bike parks, and more" that U.S. communities are poised to build — particularly following the passage of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which multiplied the amount of federal funding for cycling by roughly six.

Rather than treating those efforts as disconnected, though, the group says advocates need to start thinking of their hyper-local bike projects as part of one massive, national effort to combat climate change, cure traffic violence, and end universal car dependence — and do the urgent work of bringing transportation decision-makers together in a unified front.

"We’re trying to do this in a sprint," said Jenn Dice, PeopleForBikes' CEO. "We're saying, 'let’s build as much as we can while this window of federal funding is open. Because the window is open, and we're rushing through."

To create the first draft of the map, which Dice emphasizes is far from exhaustive, the PeopleForBikes team pored over government websites, local planning documents, news articles, and more to find bike projects that seemed to have a realistic chance of getting funded in the next few years.

Anyone is invited to submit ideas for new map entries — provided they've been proposed, approved, or funded by an official organization — and to add additional detail to each dot as it moves closer to becoming a reality. The map is also available as a searchable table, which could prove particularly useful for advocates on the hunt for similar projects in peer communities to hold up as examples to their own leaders.

Together, Dice hopes those resources will provide U.S. residents with a simple, at-a-glance overview of all the bikeability projects in the works across America, which advocacy organizations are leading the charge, and how to get involved, with links to PeopleForBikes' advocacy toolkits and case studies of successful past projects close at hand for inspiration.

The group also promises to "let [email subscribers] know when it’s necessary to take action to advocate" for a project in their region, particularly when it's in jeopardy.

"What often happens is that a project gets to implementation, the NIMBYs jump up, and the bike aspect is the first thing to get cut," Dice adds. "We want to make sure we’re shining the spotlight on these projects at those critical moments, so that they get across the finish line."

Dice is hopeful that with that kind of organizing, federal funding, and bold branding, the moment is ripe for building out America's bike infrastructure to become a national cause — and finally win big.

"We know how to get these projects done. We know how to fund them, how to build political support, how to do messaging, organizing and advocacy work to make them happen," she emphasizes.

"What we don’t have is scale. By launching this campaign, we're building on years of our pilot programs, advocacy initiatives, and experience to take it to that next level."