An increasing number of Americans would happily pay a premium to live within easy walk or bike ride to the places they go most — and with a few tweaks, that dream could be an affordable reality for far more of them than policymakers realize, a pair of new studies suggest.

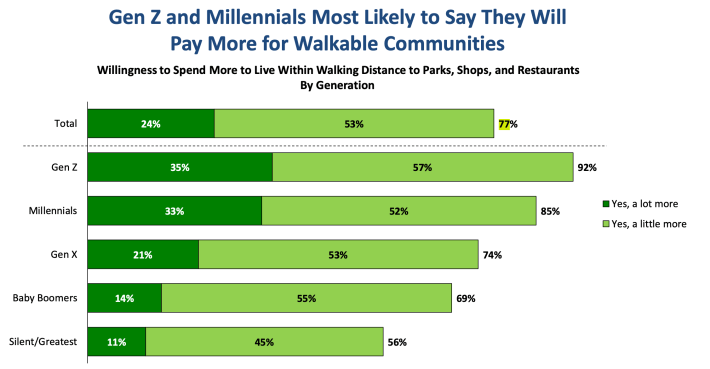

Last week, an annual survey from the National Association of Realtors confirmed, once again, that U.S. homebuyers are hungry to live in neighborhoods where they don't always have to depend on cars to get around. More than three-quarters (77 percent) of all respondents and 92 percent of prospective Gen Z home-shoppers reporting they'd pay more to live a short stroll away from parks, shops, and restaurants. (And before you ask: yes, the youths are still buying houses.)

"These preferences are rational," wrote Victoria Transport Policy Institute founder Todd Litman in his analysis of the new findings. "Living in a compact, walkable urban neighborhood reduces transportation costs, improves health, provides more independent mobility for non-drivers, and reduces commute duration. The NAR survey found that households living in walkable communities are more satisfied with their quality of life."

Getting supply to match that stunning demand, though, might not be as hard as you might think — because with a few inexpensive tweaks, millions of American neighborhoods may already be far closer to the 15-minute city ideal than policymakers realize.

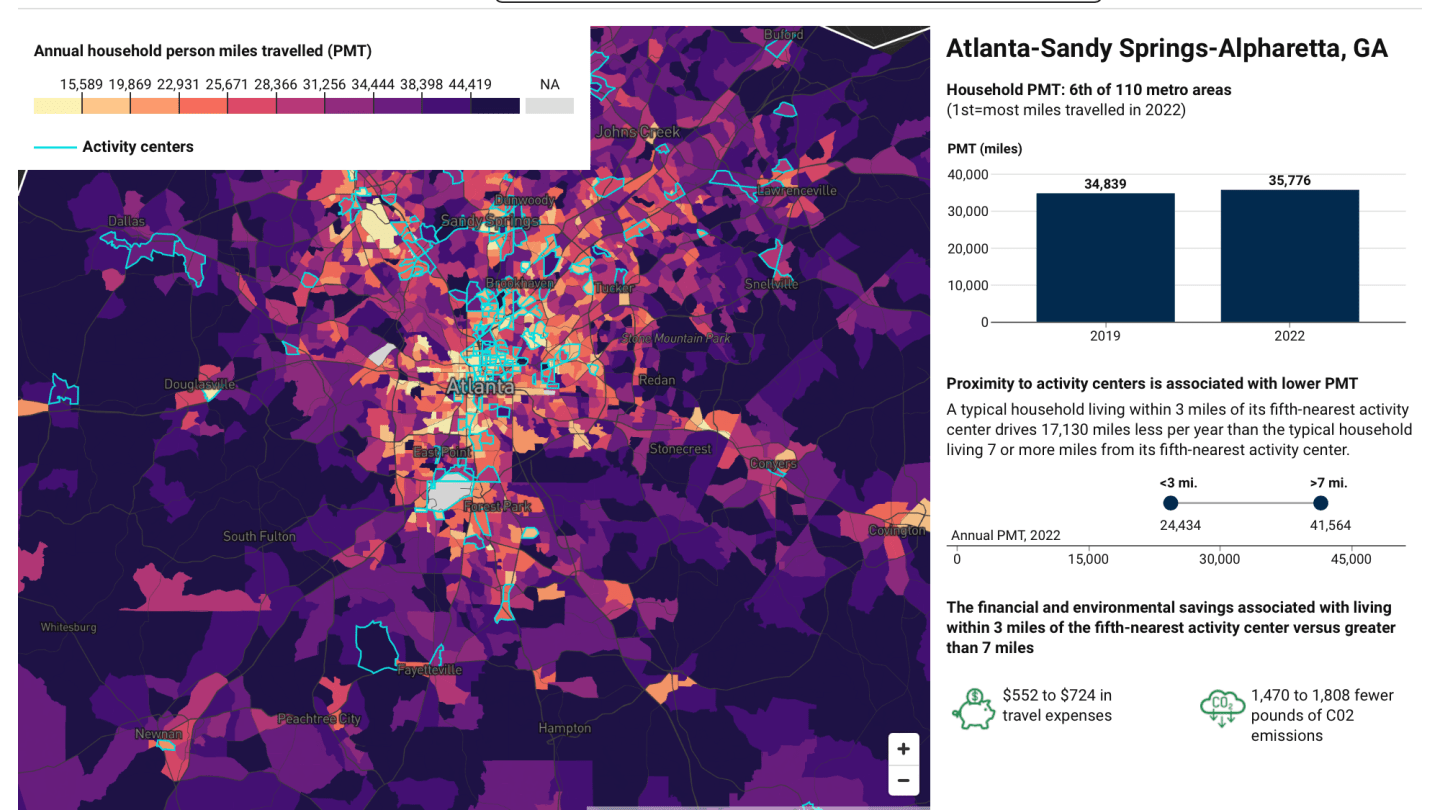

In another fascinating study also released last week, researchers at the Brookings Metro partnered with big data firm Replica to study how the travel patterns of millions of Americans were shaped by their homes' geographic proximity to "activity centers," or census tracts with at least a small cluster of shops, restaurants, employment centers, and other popular or essential destinations.

Under the researchers' definition, though, those "activity centers" didn't always look like the dense, walkable downtowns and main streets that most homebuyers are vying for. They also included standalone mixed-use neighborhoods with a handful of cafes and churches but no bike lanes, or even arterial strip malls where no one would dare travel outside an automobile if given the choice.

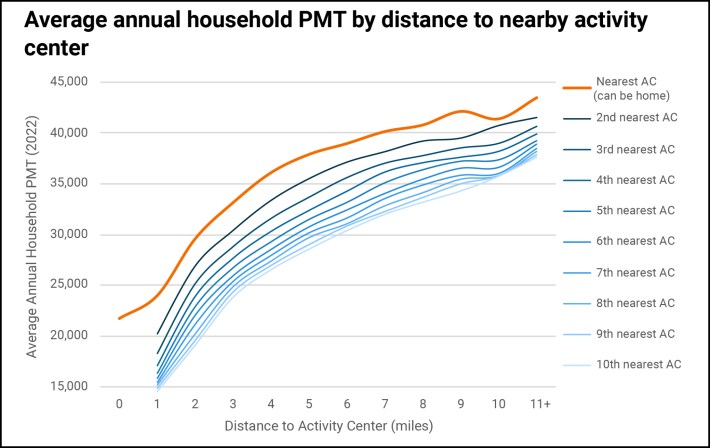

With that definition in mind, the analysts found that even in the most car-dependent places in America, a lot of people actually do live near a lot of places they should theoretically be able to walk to — and even if those busy nodes aren't reachable on foot, those residents still traveled a shocking 14,500 fewer miles per year on average than their neighbors out in the sticks.

"Activity centers," of course, aren't always walkable neighborhoods in waiting. The suburbanite who lives a stone's throw from the arterial strip mall, for instance, may never choose to travel to her nearest grocery store by bike or on foot at all; she may drive a couple blocks down the dangerous road to buy food for the week instead.

Still, the Brookings researchers point out that a 0.2-mile drive beats a five-mile schlep to a Whole Foods across town — and that on aggregate, people do tend to shop locally when given the option. A person living near multiple activity centers, they say, can expect to spend around $1,060 less in transportation costs per year than a person who doesn't, and that their carbon footprint will be about 2,737 pounds lighter, or the equivalent of charging 150,741 smart phones. And people who live within proximity of multiple activity centers typically travel even less.

"Even if someone is still in their vehicle, a shorter trip is going to reduce carbon footprint," said Adie Tomer, senior fellow at Brookings and the co-author of the report. "We know simply electrifying our cars isn’t enough; we need to reduce how much we drive, even if we don't stop driving completely. ... When we see that average trip in the US has now exceeded 10 miles, we know that’s an environment where there’s a lack of real transportation choice for people — and that we're going to have real issues actually being able to get people out of their cars."

Tomer says that to get average trip distances down even further, policymakers would be wise to, first, implement zoning reforms that allow Americans to build more activity centers in and around more census tracts, increase the housing supply in the destination-rich neighborhoods they've already got, and limit the construction of car-dependent new developments where there are few to no activity centers nearby.

He says it's also critical, though, that transportation officials identify where those clusters of services already are, and scrutinize the many reasons residents aren't choosing to visit their closest activity centers right now — as well as why they're not choosing sustainable modes to get there. For the suburbanite who lives near the strip mall, that might mean losing some lanes on the adjacent arterial so crossing the street to the grocery store isn't so deadly, or implementing congestion pricing on the highway to make the five-mile Whole Foods run less attractive, or both.

None of these approaches would transform her block into a hot-property walkable neighborhood overnight, Tomer warns. But they might help her walk a little more than she does now, and they would definitely reduce her vehicle miles traveled — and do so far faster than the decades it might take to more radically reimagine our world.

"We are not going to get rid of a lot of the roads – particularly highways — that we’ve already built," he added. "Those assets are in the ground; deconstructing an urban freeway is far more likely than an exurban and suburban one. But we can start making those streets more attractive, safer, and more enjoyable right now, particularly in these neighborhoods that we've flagged in this report."