Baltimore's Red Line is back from the dead — but will it be the kind of Red Line that activists want?

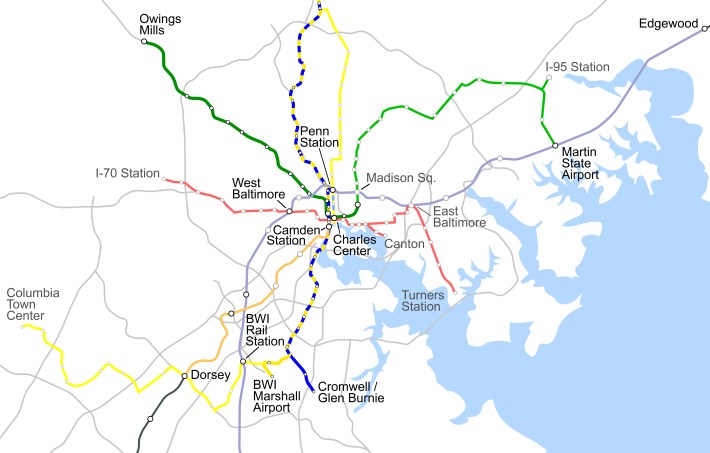

Earlier this month, Maryland Gov. Wes Moore joined state, local, and community leaders at the West Baltimore MARC station to announce the relaunch of the 14.1-mile Red Line light rail project, a lengthy plan that has gone from shovel-ready to scrap-heaped to short-listed for renewal, plus a detour in a Title VI discrimination case, over the past decade.

The commitment of Moore, a rising star in the Democratic party, is crucial, given that the prior administration’s decision to cancel the project “derailed” physical and economic mobility for Baltimore and the state, he said. Moore's predecessor, Larry Hogan, a Republican, dismissed the Red Line as a “boondoggle,” and in 2015, rejected the $900 million in federal funding. But Moore made it clear that he intends to bring the Red Line to the finish line.

But not everyone in attendance saw the pomp through rose colored glasses.

“All that glitters is not gold, as you can imagine,” said Baltimore Transit Equity Coalition President Samuel Jordan. “What I'm saying is that we are very glad that the Moore administration appears in the first instance to be taking our advice … to get the Red Line light rail project completed.”

But Jordan is at best half contented with the Moore administration’s first steps. He is frustrated by the fact that the Red Line was set to be operational by this time last year, and that the Moore announcement only marks the beginning of an exploratory phase lacking fine print or a budget. For Jordan, building the Red Line involves more than laying tracks on the ground, but confronting an ongoing history of racially charged policy making.

Jordan and his colleagues see the current Red Line light rail project in contrast to the “stolen Red Line” or the “original Red Line” to differentiate it from the rail corridor he and his community were promised, a vision he links to the fortunes of Black Baltimore itself.

As an example, Jordan cites the Purple Line, a 16-mile light rail project being built in Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties, the wealthiest county in Maryland and the second wealthiest Black-majority county in the country, respectively. The Purple Line suffered delays and cost overruns, but Hogan backed it, and it has already lured investment dollars to the area, a windfall that Jordan believes Hogan stole from Baltimore.

“[We] make sure that everybody within earshot knows that public transportation is racially conflicted wherever Black people live in this nation and there is no exception,” Jordan said. “That's why we also make it clear that people understand that Larry Hogan made the decision to cancel the Red Line after he toured the uprising zone following the murder of Freddie Gray … and he sentenced Baltimore and the region to an economic abyss.”

Gray was killed by Baltimore Police on April 19, 2015, and Hogan officially nixed the Red Line on June 25 of that year, instead directing funds toward road projects in largely white suburban and rural parts of Maryland where Hogan reportedly held real estate interests, a charge he denied.

In response, Jordan and other activists filed a Title VI complaint against the state, arguing that canceling the Red Line violated the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The federal Department of Transportation dismissed the suit in 2017, but plaintiffs continued organizing as the Baltimore Transit Equity Coalition.

Jordan said BTEC challenges more than what he considers state-level racism, explaining that many Marylanders deride the Red Line light rail project — which would pass through the Inner Harbor and wealthy neighborhoods like Canton and Fells Point — as the “loot rail.”

“That's the repetition of this slander that Black folks in West Baltimore want a light rail so they can hop on rail, go to Canton, and steal televisions,” Jordan said. “We need a clear demarcation between the Hogan era and the Moore era and it will be assessed at its sharpest on the question of transportation.” (One demarcation? Moore’s Lt. Gov. Aruna Miller is a professional transit engineer.)

In a press release following the relaunch event, the governor’s office said that the Maryland Transportation Administration will get community input, as well as review the original Red Line plan and the Hogan administration’s East-West Corridor Feasibility Study for guidance.

Jordan has his doubts about the study, which contains alternatives that are similar, but not identical, to the original Red Line. Now, he is calling on the governor to deliver “the correct Red Line.”

“That's the Red Line we want him to complete,” Jordan said. “And that's the shortest amount of time it would take. If they do anything else, you have to start from scratch.”

Jordan sees the Red Line as a web of externalities, good and bad, and he wants the ostensibly pro-transit new governor to grasp the full extent of what’s at stake. In 2021, BTEC, Johns Hopkins University’s Bloomberg School of Public Health, and Baltimore community members co-authored a study on the social and environmental impact of inadequate public transit in Charm City. The study made a spatial and empirical argument for transit as a vector for better outcomes in the city’s “Black Butterfly,” a term used to describe Baltimore’s wing-shaped belt of historically Black neighborhoods. Jordan believes that the Red Line can help address the social issues targeted in the study, but he cautions that Black communities can anticipate gentrification pressures, too.

A longer-term goal? Compelling, possibly through a ballot referendum, the City of Baltimore to create a Baltimore regional transit authority. Jordan hopes that a BRTA can replace the “commandist model” of the MTA — which, under Hogan, literally did not include the City of Baltimore on its transit spending map — with a mechanism that prioritizes Baltimore and may even curtail the powers of “George Wallace wannabes,” as Jordan put it.

“When you find structural racism you've got to make structural change,” Jordan said.