Only a handful of U.S. cities are successfully slowing down drivers to less-lethal speeds on roads where lots of people are walking — while most are failing to do so, whether or not their speed limit signs say that it's time to hit the brakes.

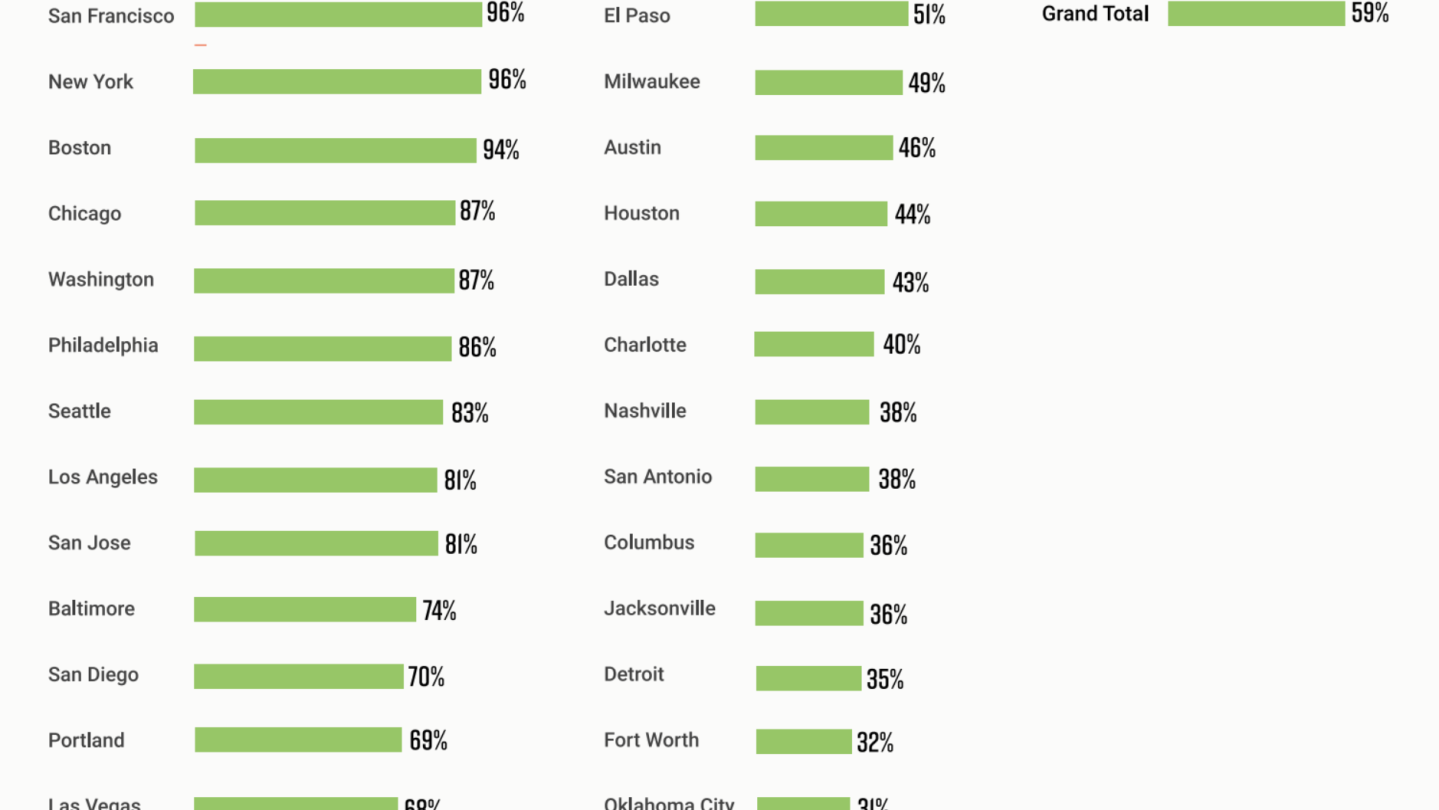

In a new study traffic analytics firm Streetlight analyzed anonymized data from millions of cell phones in America's 30 biggest cities to better understand where people are walking the most, and how fast motorists are going in their midst.

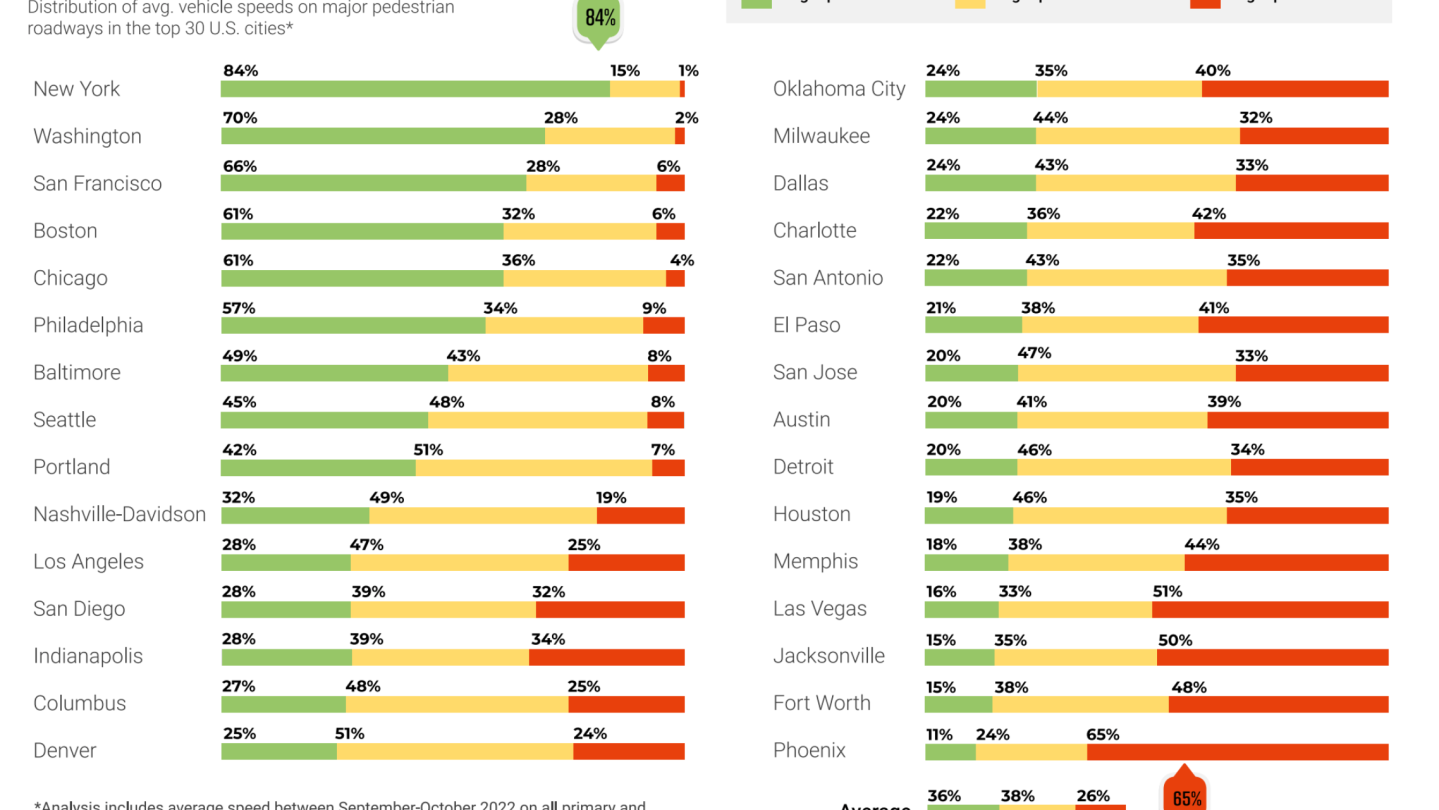

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the researchers found that a whopping 96 percent of city blocks in New York City clocked more than 200 pedestrian trips per day, and that drivers averaged 25 miles per hour or less on 84 percent of those streets. In nearly every other city on the list, though, going slow was relatively a rarity, with 24 out of 30 communities reporting that most of the roads with heavy pedestrian traffic experienced faster speeds on average.

That's bad news for walkers, considering that most experts say 25 miles per hour is the absolute upper bound of what any policymaker should consider acceptable in places where people travel outside cars. Pedestrians struck by vehicles going 25 miles per hour will survive nine times out of 10; at speeds over 35, fewer than half will live.

Of course, that's also not exactly great news for walkers on the 16 percent of New York City streets frequented by pedestrians where drivers didn't stick to pedestrian-friendly speeds — and its even worse news for residents of Phoenix, where a surprising 52 percent of street segments reported more than 200 pedestrians an hour, but 65 percent clocked average driver speeds of 35 miles per hour or more.

And once again, the Valley of the Sun isn't alone: of the 30 most-populous cities in America, just six (New York, D.C., San Francisco, Boston, Chicago and Philadelphia) reported that a majority of roads were even close to slow enough to safely allow for human movement outside cars.

The study comes one day after the latest grim update on the decade-long pedestrian death crisis in America. In 2022, more than 7,500 people outside cars were killed in crashes, the most in 40 years.

Notably, the authors of the study chose to look rates of speed rather than rates of speeding, since many of the dangerous drivers picked up by their data were likely following the letter of the law.

Many states explicitly recommend 35 mile per hour speed limits even in residential areas, and some don't allow cities to set lower ones on their own roads, even when residents demand it. Other states do allow cities to set their own limits, but not on many of the arterials where 67 percent of walkers lose their lives, which are typically state-maintained.

In car-dominated contexts like Phoenix, arterials are also often home to much-needed destinations like grocery stores and apartment complexes to which people frequently walk — even if they're not designed like it.

"There are services in these places," said Martin Morzynski, Streetlight's senior vice president for marketing. "There are universities where young people walk to bars and restaurants; there’s commercial infrastructure; there's all these things that are close enough to walk to, but cities haven’t taken action to reduce speeds.”

Morzynski cautions the least car-reliant cities on the list, though, not to rest on their laurels.

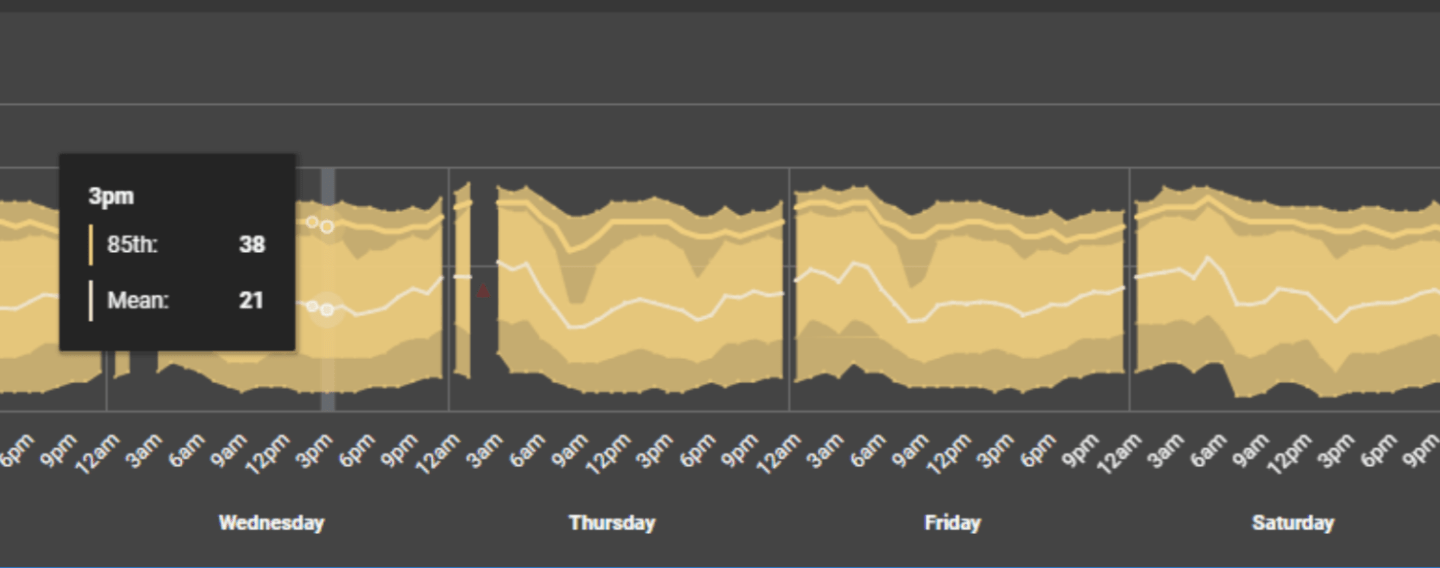

He points out that even on the safest roads, drivers often exceed all-day average speeds during late-night hours when congestion thins out, at least if other things don't slow them down, like good road design. Moreover, averages don't capture the inequitable toll that speed-related traffic violence takes on communities of color and low income, though Streetlight says their data can be overlaid with aggregated demographic information to give cities a sense of where their traffic-calming dollars would have the most impact on safety and equity concerns.

“Averages are a stepping stone to more rigorous and hyper-local analysis," he added. "Just because 84 percent of roads in New York City are relatively slow, well, 16 percent are still fast. ... It’s about looking deeper, finding those stretches of road where lots of pedestrians and cars come together, and overlaying those stats with crashes, fatalities, and other data. That’s how you identify the 15, 20 intersections you should address first.”