Just like pedestrians, bicyclists who are struck by SUV drivers endure significantly more severe injuries — particularly to the head — than those struck by the drivers of smaller cars, according to a new study that adds to a mountain of evidence that regulators should do more to rein in deadly vehicles that are increasingly dominating U.S. roads.

Researchers at the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety scrutinized a sample of bike/car collisions in Michigan that contained significantly more detail than the average U.S. crash report, in hopes of better understanding what, exactly, happens to the average biker's body when she's struck by a megacar.

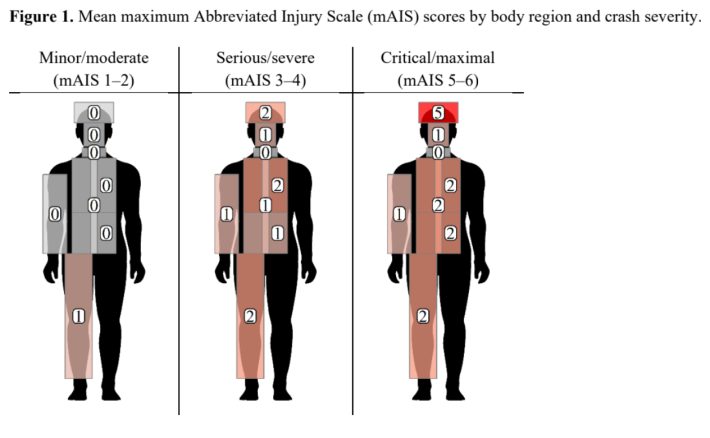

The answers weren't pretty. According to the Abbreviated Injury Scale — a medical coding system that grades the severity of harm caused to the body after a trauma — cyclists hit by SUVs sustained injuries that were 55 percent worse than those struck by smaller vehicles.

Those unlucky cyclists also endured 63 percent worse head traumas, which the researchers attributed to the fact that SUVs crashes were more than twice as likely to cause "ground impact" injuries — or, in plain language, to knock cyclists off their bikes completely and onto the pavement, causing a second impact that can be even more damaging than the initial contact with the car itself.

Moreover, SUVs were the only vehicles in the sample that actually ran cyclists over, while sedans almost universally pushed cyclists up onto the vehicle's hood or roof. That critical difference, the researchers speculate, has to do with the size and shape of the SUV's front end, which is more likely to strike a vulnerable road user near their center of gravity.

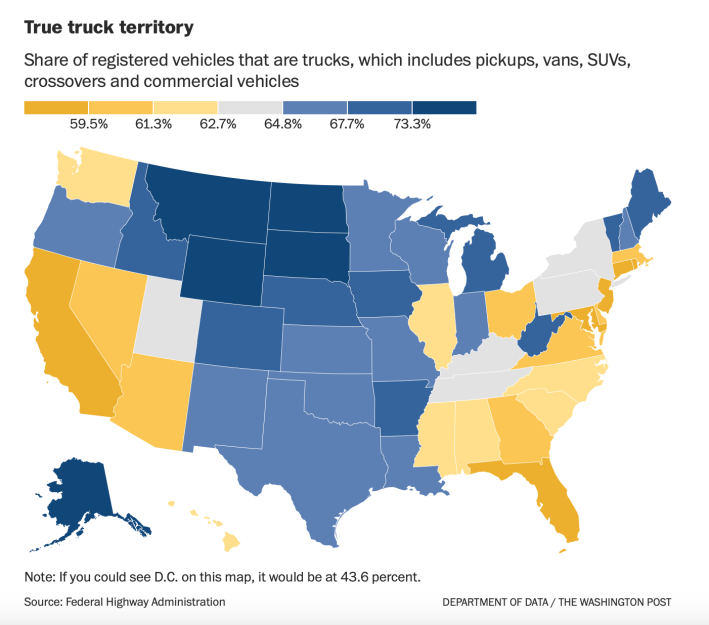

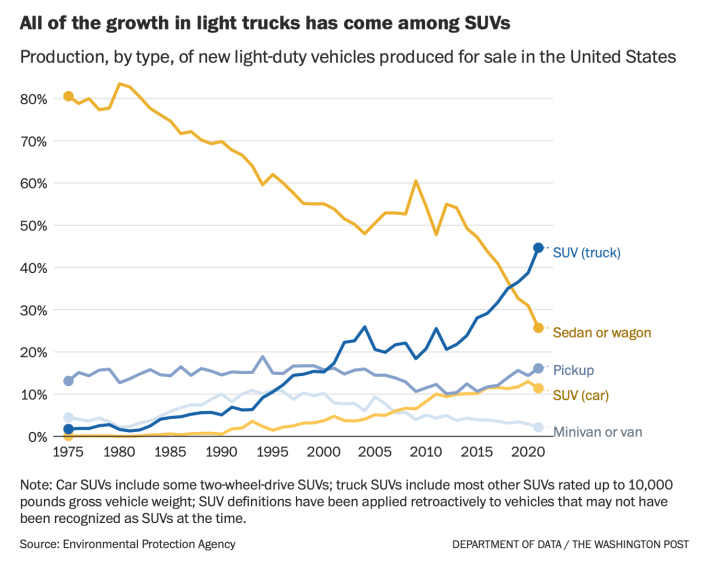

Those gory details may help explain why SUVs are so vastly overrepresented in the nation's road violence stats, even after accounting for the fact that the vehicle class comprised 57 percent of new cars sales last year, and make up a significantly higher percentage of registered vehicles in many states. According to one recent study, SUVs were the striking vehicle in 15 percent of U.S. crashes with pedestrians and cyclists since 2009, but were involved in 25 percent of fatalities.

Despite those horrifying statistics, though, experts have been hesitant to definitively say why, exactly, SUVs are so much more lethal to vulnerable road users, even as evidence mounts that they're a leading factor in America's escalating death crisis among pedestrians and cyclists alike.

In recent years, researchers have found evidence that wide A-pillars that create blind spots when drivers turn, huge front blind zones that make people and objects directly ahead of vehicles virtually impossible for drivers to see, and even high headlights that blind other motorists on the road may all be making SUV crashes more frequent, or more lethal to vulnerable road users when they do. But those findings haven't always translated into hard recommendations to regulators to disallow specific vehicle features, recommendations to Congress to write policies to discourage SUV sales. (Interestingly, the researchers found that heavy SUV weights are likely not a major factor in how deadly crashes end up being, because cars in general are so much heavier than human bodies in the first place — though they are an important factor in vehicle to vehicle crash severity.)

"Every study gets us a step closer towards getting the answer — and it does seem likely at this point that it’s the higher front end [that's playing an outsized role]," said Sam Monfort, IIHS statistician and the lead author of the study.

Until that answer is definitively found, bike advocates have pushed the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration to, at the very least, consider the safety of people outside the car when they test SUVs in the lab — and warn the public that their favorite large vehicles are more likely to be injurious to the people they strike, as Europe's New Car Assessment Program has done since 1997.

And Monfort says that's only the first step — and that agencies at every level of government have a role to play.

"I get the frustration; I’m impatient too," added Monfort. "Vehicle design matters, but a safe systems approach is the one we want to take. ... If we reduce speed limits in places where a lot of vulnerable road users are, that can have a huge impact; infrastructure changes like protected bike lanes, automated enforcement can have an impact too. There’s plenty we can do in the meantime to save lives while we wait [to figure this out]."