The reasons why so many Americans pick up their phones behind the wheel are more complicated than policymakers assume, a new study argues — and until we dive deep into the psychology of distracted motorists, we'll struggle to convince them to stop or win support for systemic solutions.

In a new paper from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, researchers surveyed a nationally representative sample of more than 2,000 U.S. drivers who own cell phones, roughly half of whom openly admitted to engaging in distracted driving behaviors like texting and making calls behind the wheel. That survey, though, didn't just bluntly ask them why they did it, but dug deep into the many factors that underlie such a dangerous decision, including:

- Their perceptions of how big of a threat distracted driving actually poses to themselves and others; that is to say, whether a motorist truly believes that taking just one call could actually result in a crash, injury or death.

- Their perceptions of the personal and societal benefits of putting down their phones; e.g. whether they actually believe that changing their behavior can prevent a crash, give themselves a greater feeling of overall safety, or a result in a lower insurance premium.

- The "barriers" they face to not driving distracted, or the reasons they feel they have no choice but to do it; e.g. a boss that requires an answer to every email within minutes, a call from a child's school that a parent feels she simply can't wait to answer until she can pull over.

- They're thoughts on their own "self efficacy," or their own ability to successfully overcome those barriers — or simply to resist the temptation to fiddle with their phones.

- The specific cues to action that would actually motivate them to change their behavior — and which ones they'd likely just ignore.

That kind of thorough analysis, said study author Aimee Cox says, is based in the famous Health Belief Model pioneered by social psychologists in the 1950s — and without it, she said policymakers will struggle to identify interventions that will save the more than nine people who die in distracted driving crashes every day. And the numbers she stresses is likely an underestimate, because distracted driving stats are challenging to track.

"We can implement countermeasures and encourage people not to drive distracted, but if we’re not addressing the fact that a lot of drivers downplay the threat of distracted driving, we probably won't reach them," Cox added. "And at the same time, if we’re not addressing the top barriers [to paying full attention to the road], those countermeasures may not even work. It’s important to address this problem from all possible angles."

I'm very aware of distracted driving, anyone who walks or bikes can see it constantly. Are we going to DO anything besides asking nicely? https://t.co/UlOGSIdAAG

— Ollie Oliver (@Ollie_Cycles) April 4, 2023

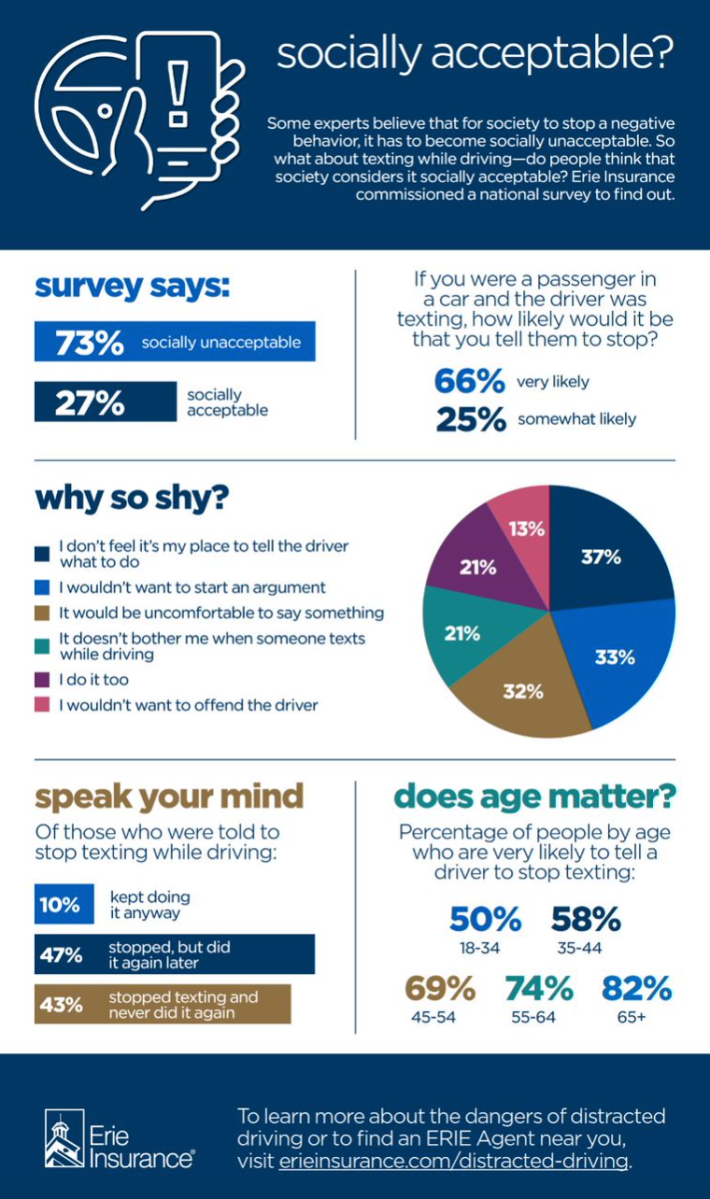

Despite the stereotype that U.S. drivers are simply ignorant to the dangers of phone use behind the wheel, the survey found that the majority of U.S. drivers do understand why distraction is so deadly — and moreover, a lot of them care about how those behaviors effect their neighbors. A full 84 percent of the sample "agreed that the potential consequences that best motivate me to not use a mobile device while driving are ... injury to others," while 81 percent listed "fewer injuries and fatalities" as a primary benefit of giving the road their full and undivided attention. (Habitually distracted drivers, unsurprisingly, were less likely to agree with both statements.)

When it came to actually putting the phone down, though, many of those drivers struggled to follow through, for potentially surprising reasons. A full 53 percent said that "being lost and in need of direction" from phone-based or dashboard GPS services prohibited them keeping both hands on the wheel, while 46 percent believed that "family related calls or text" sometimes simply needed to be answered while the car was in motion.

An earlier Institute study found that parents are 50 percent more likely to engage in smart-phone enabled distractions — second only to gig economy workers like app taxi drivers, who were four times more likely to do so, in large part because "their jobs require them to interact with their phones while they’re on the road,” IIHS President David Harkey said.

All those "barriers" to safe, attentive driving, of course, can be dismantled with good policy, like mandating that automakers, cell phone carriers, and employers of people who drive for a living restrict on-board devices to hands-free and voice-activated modes only whenever the car is in motion. In one LA Times article, some experts even argued that phones should automatically shut off the moment the device senses that it's in the hands of any vehicle occupant, forcing drivers to pull over before they touch a phone — though that argument was made way back in 2013, when 56 percent of US adults owned a smartphone, compared to 85 percent in 2021.

Until regulators do any of those things, though — and given Americans' rising reliance on cell phone screens and dashboard tablets, it doesn't seem likely they will anytime soon — or until they redesign road networks that actively encourage drivers to tune out, Cox argues that policymakers should pursue more pragmatic, short-term solutions.

"Unfortunately, it just doesn’t seem it’d be very popular among the general population to completely block out cell phone capabilities in moving vehicles," she added. "But if you can still stream music and set the GPSwhile keeping your eyes on the road and your hands on the steering wheel? You can still prevent a lot of visual-manual distraction."

Even less gentle strategies to curb distraction, the researchers found, might not prove as politically challenging as they seem. Cox and her colleagues noted that "most" of the drivers surveyed "supported a blocking feature that does not require the user to opt in and would automatically turn on each time the driver is in their vehicle," and a surprising 61 percent "indicated interest in their next vehicle having a driver monitoring system to track and alert the driver when their eyes have been off the road for too long."

The IIHS team also pointed to earlier research that found that 83 percent of drivers were actually in favor of anti-distraction laws, with a narrow but still significant 53 percent of their own sample specifically supporting camera enforcement of those offenses.

The survey respondents said that most effective deterrent to distracted driving, though, wouldn't come from an automaker or a police department at all, but from someone they know personally. A whopping 83 percent said they would be less likely to drive distracted if "someone they cared about" reminded them that "you could hurt or kill someone" by driving distracted, which made it the most potentially impactful countermeasure explored in the entire 63-question survey.

That result suggests that until more systemic solutions can be pursued, policymakers should probably direct their educational campaigns not to motorists themselves, but to their passengers — and perhaps especially to their children.

"When you think about all the things that could be done in school settings, not just with young drivers learning to drive but even earlier than that — I think that’s a really great place to start," added Cox. "We need to inform people of the dangers of distracted driving, but also, to encourage open dialogue and being comfortable saying to to your loved ones or your family or friends that you don’t feel safe when you're a passenger in a car with a driver who's texting. It seems like a lot of folks would respond to those messages."