The swelling size of the average car on the road is threatening the environmental potential of EVs more than proponents may realize, a prominent watchdog group warns — and that's in Europe, where vehicles are significantly smaller and cleaner on average than they are in America.

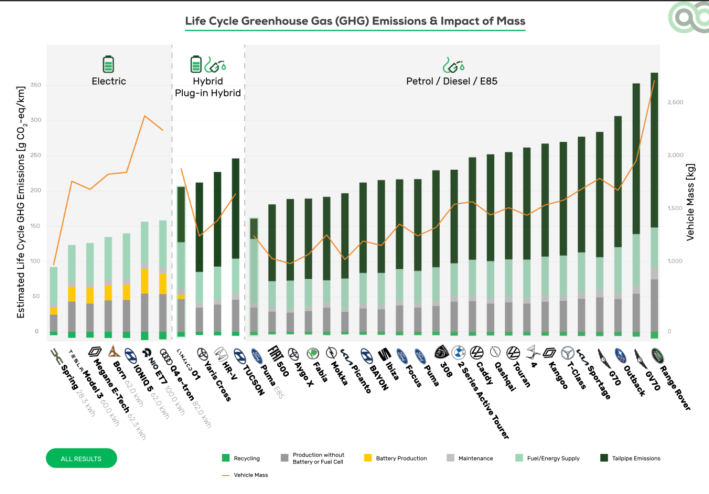

In its newly released annual vehicle ratings, the independent researchers behind the Green New Car Assessment Program compared the lifetime environmental impact of 34 cars, including models that run on gas, diesel, battery electricity, and even bio-ethanol. That measure, though, included not just the greenhouse gas emissions from tailpipes, but also the emissions created during the manufacture of the vehicles, in the process of recycling them when they reach the end of their useful lives, and, in the case of EVs, the proportion of renewable and non-renewable sources that powered the grid off of which the battery was charged.

The researchers also controlled for the number of kilometers that vehicle was likely to be driven each year, and offered a free tool for motorists to estimate their cars' unique stats if they drive less than their countries' annual average, or if their vehicles weren't chosen for deeper analysis in this year's rankings.

"To understand the full impact of a vehicle, you need to consider this product from cradle to grave with all the processes related to its lifecycle," said Aleksandar Damyanov, technical manager for the organization. "A lot of the environmental impacts of [manufacturing a car] are hidden; a lot of it happens before the vehicle comes to the streets, or when it reaches the end of its useful life. The consumer usually doesn't see what happens to it then."

Seen through that expanded lens, Damyanov stresses, cars that are colloquially called "zero emission vehicles" even by major government programs are anything but — and large ones, especially, can have fewer environmental benefits than their green marketing campaigns might suggest. Overall, the electric vehicles in this year's dataset only cut between 40 and 50 percent of the greenhouse gas emissions compared to conventional petrol cars, rather than the 100 percent that the famous ZEV label implies.

Of course, those are still impressive reductions — but they're not nearly as good as they could be if the average EV were simply smaller. Though any electric car on the road will be roughly 33 percent heavier than its gas-powered equivalent thanks to its heavy battery, the researchers stressed that Europe's nine percent increase in average vehicle weights on newly sold vehicles over the last ten years was also driven by another factor: the exploding popularity of large SUVs, whose sales increased sevenfold over that period. Sales of small SUVs, meanwhile increased five times over, becoming the most-sold vehicles in 2022, many of which were outfitted with the extra-weighty batteries necessary to move a weighty chassis.

"The overlying message is clear – the heavier the vehicle, the more harm it does to the environment and the extra energy required to drive the car," the researchers wrote. "In general, battery electric vehicles emit significantly less greenhouse gases over their lifetime, but some of the gains are lost due to their increased weight."

The average weight of the vehicles sold in Europe and USA has grown by 21% and 11% between 2001 and 2022, respectively. Why?

— Car Industry Analysis (@lovecarindustry) March 13, 2023

- bigger dimensions

- more EVs

- more SUVs, trucks

Source: JATO#carindustryanalysis #felipemunoz #cars #automotive #carexpert #carinfluencer pic.twitter.com/AeJLg2vggW

Editor's note: Converted from kilograms, average European vehicle weights have grown from 2,927 pounds in 2001 to 3,527 in 2022, or an increase of 20.5 percent. US vehicle weights have swelled 11.4 percent over the same period, but they were 29 percent heavier than European cars to start with, and remain 19 percent heavier today.

Of course, weighty vehicles have been a weighty problem in America for far longer than they've been in Europe — even though we've been far slower to embrace lithium-ion tehcnology. In the U.S., even large SUVs and pick-ups are generally far larger than can be legally sold across the pond, and claim an even larger share of the vehicle market, bulking up the average ride despite the slow adoption of EVs. In 2020, the average weight of a new car sold in the U.S. swelled to a staggering 4156 pounds compared to Europe's 3,086 pounds — a difference roughly equivalent to the mass of concert grand piano or a plump baby elephant.

And all that added mass has big consequences for vulnerable road users. American SUVs are significantly more likely to kill a pedestrian in the event of a crash, particularly for children, who one crash analysis found were eight times more likely to die when struck by one than a smaller passenger car; road safety experts consistently name them as a prominent reason why pedestrian deaths have increased 59 percent since 2009, when such models really took off.

Europe's own SUV explosion hasn't resulted in a pedestrian death crisis of anywhere near that scale, likely thanks to the fact that Europe requires them to be tested for vulnerable road user safety addition to occupant safety — and the fact that its nations tend to provide many other layers of systemic safety interventions to protect people who walk and bike. Nonetheless, many EU countries are taking vehicle weight concerns seriously from an emissions and safety perspective, including Norway, which recently implemented new taxes on heavy cars, with no exemptions for EVs.

Damyanov is hesitant to prescribe any specific policy to America, but his research suggests that lawmakers should consider following suit — for the safety of the planet and pedestrians.

"In the end, policymakers should target the same things that we are targeting: minimizing the negative impact of transport on the environment, and maximizing the benefits for consumers," he said.