Washington D.C. has struggled to bring down road fatalities because its Vision Zero program is hampered by limited infrastructure improvements, low funding and inconsistent oversight, part one of a new audit reveals.

The report comes as cities face rising traffic and pedestrian fatalities and public criticism of Vision Zero’s effectiveness; Seattle’s Vision Zero program recently released its own “top-to-bottom review” and a similar report is forthcoming in Los Angeles. And the trend shows that achieving change is hard where the rubber actually hits the road.

“It’s easy to provide funding for a new program,” said D.C. city auditor Kathleen Patterson, who wrote the report. “But following through, and circling back to say, 'what is effective'? There is less attention paid to that.”

The first part of Patterson’s study focused on engineering strategies, while part two will look at enforcement — something that District dwellers may find particularly newsworthy following a recent horrifying fatal crash involving a driver with more than $12,000 in unpaid traffic citations. The need for strong central leadership and communication across multiple agencies is expected to be recurring theme of both reports.

“There's a need for more dedicated staff to be doing Vision Zero and road safety work. And I would say that that is definitely true [in] every city that's pursuing Vision Zero,” said Jenny O’Connell, senior program manager for the National Association of City Transportation Officials. “It's not just about having the time and the resources or the funding to put those kinds of projects in the ground. It's about having the staff that are dedicated and the time to be able to do that.”

More than 50 communities — areas as large as Hillsborough County, Florida, large cities like New York City, Los Angeles and Chicago and smaller cities like Chapel Hill, N.C. and Hoboken, N.J. — have adopted a Vision Zero approach, which holds that traffic deaths are particularly preventable through engineering, since humans inevitably make driving mistakes. The program also calls for governments to educate citizens on safe practices and implement data networks and policy that provides safe, accessible and modernized transit infrastructure. Another pillar is solid enforcement.

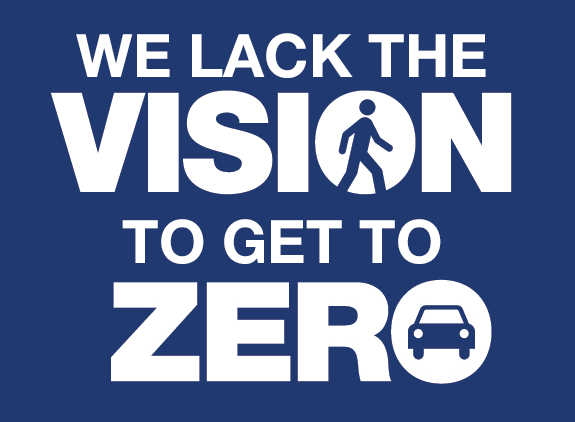

Skeptics, though, point out that many cities that have adopted Vision Zero plans aren't yet setting results. In Los Angeles, for example, there were 312 traffic deaths in 2022, its highest total in 20 years. In Denver, traffic fatalities have risen every year since Vision Zero was adopted in 2017, making it a focus of the April mayoral election.

But the nation’s ongoing road violence problem — which Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg declared “a national crisis” in January — is the result of about a hundred years of bad decisions that cannot be undone overnight or under-budget, say Vision Zero supporters.

“Every single city … is up against a century of decisions and policies and designs that have really prioritized the fast movement of cars above the safe movement of people,” says Leah Shahum, founder and executive of Vision Zero Network. “If anyone thought that turning around a century of investments in speed over safety was going to happen in five or six or seven years, they were sorely mistaken.”

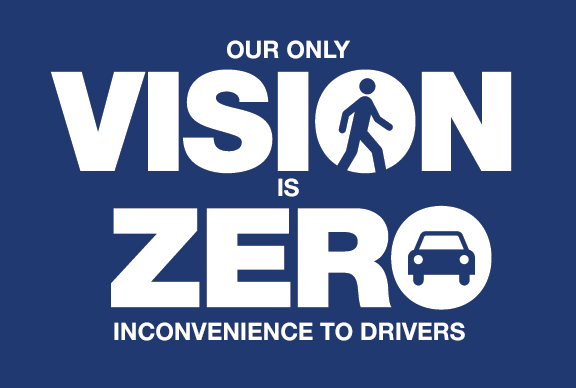

Many Vision Zero strategies focus on reducing car speeds by shrinking lanes, redesigning roads, reducing speed limits or simply building highway infrastructure that makes it impossible to speed. But those tactics can be a challenge in a country that's long prioritized the fast movement of vehicles, ample parking on public streets, and the notion that "freedom" to drive outweighs the oppression of pedestrians and cyclists, whose fatality numbers are on the rise, said Shahum.

“There's been a century of investment in certain kinds of roads, certain kinds of cars and certain kinds of expectations that prioritize speed over safety,” Shahum said. “There is a public good that comes with roadway safety; I don't think we've seen leaders embrace that and champion it enough.”

According to the Seattle Department of Transportation, pedestrians and cyclists only accounted for 7 percent of the city’s collisions between 2016-2021, but 61 percent of traffic fatalities. And those pedestrian fatalities occur overwhelmingly on arterials — roads designed for higher speed limits and high-volume traffic — and not in neighborhoods.

Engineer Bill Schultheiss of the influential firm Toole Design insists that redesigining infrastructure is one of the foremost challenges of improving traffic and pedestrian safety. Logically, he says local departments of transportation should be taking measures like installing more walk signals, bike lanes or stoplights around dangerous intersections to crashes vehicles. Instead, that is where the bureaucratic nightmare begins.

For example, the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices states that before action can be taken, five or more crashes “susceptible to correction by a traffic control signal” must occur in 12 months and that each crash must involve injury or significant property damage. The five-crash number is cited in remarkably similar language to the 1937 manual, which Schultheiss sees as a number with no basis. And that is one of three criteria that must be met for the stoplight to get a green light.

“I can’t install a signal at an intersection that I know is dangerous and has near-misses all the time,” Schultheiss said. “I have to wait for five people to be killed or injured first.”

Schultheiss cites the natural risk aversion of most engineers, people trained to form conclusions from exhaustive research and prefer iterative change to major overhaul, as a driving factor for the lack of action on traffic safety.

“We have a serious safety problem in this country,” Schultheiss said. “Engineers [need] to understand that some of the design guidance they're relying upon is outdated [and] to continue to rely on it as a reason you cannot do something is just gonna prevent us from getting to Vision Zero.”

Also, many cities have no control over the designs of state roads that run through them, such as when Texas overruled the city of San Antonio, which wanted to put a 2.2-mile stretch of Broadway Avenue on a road diet. Arterials like Broadway Avenue are the site of nearly 20 percent of traffic fatalities yet comprise just 2 percent of streets, NACTO said.

And during the pandemic, speeding increased dramatically, along with the increasing popularity of exceptionally large trucks and SUVs. But the federal government has not regulated vehicle design.

Even if a Vision Zero city is suffering from administrative bloat, political gridlock or widespread reckless driving, cities still have plenty of ways to improve traffic safety. In 2023, Seattle will phase in more “no turn on red” intersections and crosswalks that let pedestrians walk before a stoplight turns green. In D.C., Mayor Muriel Bowser’s proposed FY 2024 budget would add 342 speed cameras across the city. For Schultheiss, a 25-year resident of the district, it’s impossible to ignore the changes in local infrastructure.

“DC has been implementing changes rapidly throughout the city in the last three to five years that are unprecedented,” he says. “All the flex posts, bike lanes and curb extensions … it's incredible. I think the audit picked out some very real challenges that every agency is struggling with. Is it fast enough? And are we being responsive to the citizens who are asking for change?”