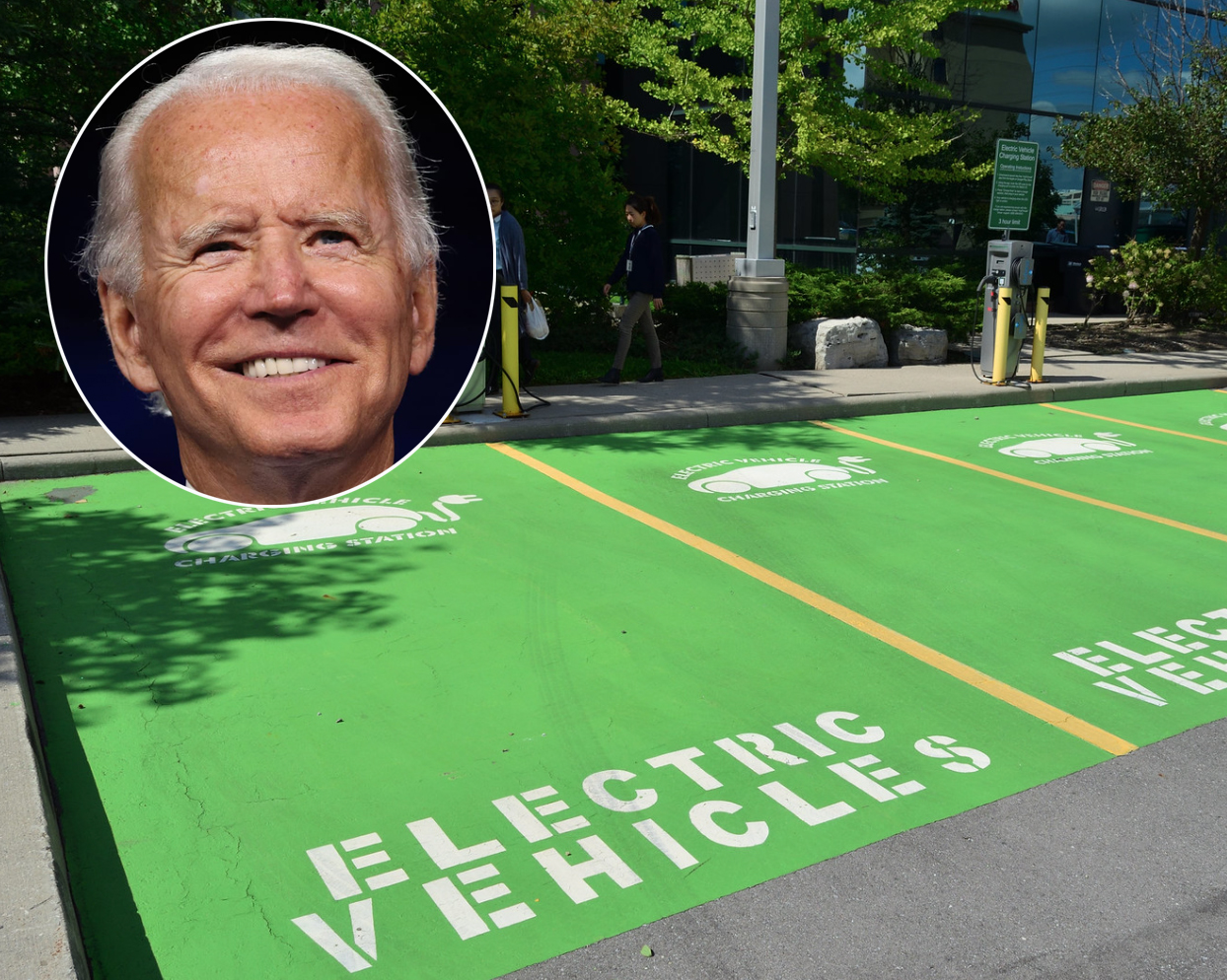

The Biden administration wants to erect a multi-billion dollar network of charging hubs for electric vehicles, but advocates warn the country can’t drive its way out of the climate crisis, whether cars run on fossil fuels or electricity.

This month, the federal Department of Transportation began accepting applications from states and cities seeking a piece of the $2.5-billion Charging and Fueling Infrastructure grant program, which seeks to build half-a-million plugs for the growing number of electric vehicles on the roadways. Along with a $7,500 clean vehicle tax credit, the Biden administration claims the EV initiatives will slash carbon emissions in half by 2030.

In addition to being insufficient in the short term, some advocates fear the program could spark new skirmishes over lucrative curb space and lock municipalities into keeping their thoroughfares car-dependent for generations.

“It’s insane to open curb space for electric vehicle charging,” said Jon Orcutt, advocacy director of Bike New York. “It’s uniquely American to think technology is the thing that is going to fix everything, but if you want less car traffic you have to apply the right policies regarding road policy, like increasing the cost of driving and creating alternatives that are better.”

The Federal Highway Administration’s grant program aims to help states, cities, and towns install expensive, high-voltage infrastructure in urban and rural communities. A separate FHWA initiative, the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program, is forking over $5 billion to state transportation agencies to build charging stations alongside interstate roads and freeways.

Lodging charging stations at highway rest stops will ensure drivers will be able to travel long distances without getting stranded. But determining where to plunk EV stations in dense urban quarters, sprawling suburban developments, and bustling downtown corridors shared by curbside bike paths and bus lanes is another matter.

For this round of awards, federal transportation officials are prioritizing publicly accessible areas, such as parking lots and garages at government buildings, schools, and parks, as well as public streets in underserved communities.

Once a municipality decides where to put a station, it will likely remain there for years since the site would be creating a contract with a utility company to provide the power. That could preclude local governments from converting a street into a protected bike lane, a pedestrian plaza, or an outdoor dining facility in the future.

“The really important thing is where these chargers are sited. You can’t just plug them in,” said Alex Engel, a spokesman for the National Association of City Transportation Officials. “The work that’s done is expensive and once one is installed, it’s unlikely to be moved. We’re encouraging cities to think about putting them in places where they wouldn’t want to use that curb site for a different purpose.”

Situating high-voltage infrastructure in larger cities could be even more complicated, as multiple government agencies that regulate building codes, sewer and water lines, local zoning, and electric grid, not to mention neighborhood community leaders, will need to be on board.

Chris Rall, outreach director at Transportation For America, believes any new EV station must serve as a mobility hub for the surrounding community, providing outlets for electric bikes and scooters, or car shares instead of only single-owner vehicles.

“In general, they’re designed for cars so their opportunity may be limited,” he said. “We need an overall strategy for other investments in biking and walking infrastructure to make it easier for people to not have to drive so much.

But the existing federal EV grant program does not include any strategies to bolster transit ridership or encourage municipal fleets to electrify. Billions of dollars are essentially being spent to further the public’s dependence on cars with little benefit to those who cannot rely on one.

“In a place like New York City, most people don’t have a driveway and street parking is limited,” said Jaqi Cohen, director of Climate and Equity Policy at Tri-State Transportation Campaign. “Why are we building new infrastructure for car owners without thinking of public transit riders? We need to have both.”

It has been well documented that electric cars will not provide the planet with the quick fix it needs to arrest climate change.

The total market for EVs is growing, but so too is the total market for cars. By 2035, nearly two billion cars will be on roads around the world. In 2010, 14 percent of the world’s emissions came from transportation. Total emissions have continued to rise in the last decade, with transportation’s share increasing commensurately. This is important because if the nation's of the world hope to limit global warming to the critical threshold of 1.5 degrees, they'll have to reduce total emissions by 55 percent by 2030.

Even if every single car were electric by 2030, and all production was carbon neutral (which isn’t possible), global emissions would only drop between 15–20 percent — far short of the estimated 55 percent that is needed to be cut. While the reduction would be greater in the U.S. as transportation comprises a higher proportion of our emissions than at a global level, it still isn’t enough. Carbon emissions care little for international borders.