Replacing human drivers with self-driving taxis might not actually remove many space-wasting parking lots from dense American cities, according to a new study that throws doubt onto one of the core arguments in favor of the autonomous vehicle revolution.

For decades, AV proponents have envisioned a world where self-driving cars would liberate humanity from the need for personally owned automobiles by shifting trips onto circulating robotaxis, eliminating the need for virtually all garages and surface lots and freeing up precious land for housing, human-centered businesses, and other, better uses in the process.

“On the surface it makes sense; the car comes and picks me up, I get where I’m going, and then it leaves and picks up someone else,” said Nico Larco, director of the Urbanism Next Center at the University of Oregon. “We want it to make sense, because parking is one of the largest limiters of urban form, and the benefits of reducing it are enormous.”

Those who sought to prove the possibility of that vision, though, have mostly relied on abstract models of theoretical cities — and the results were, predictably, all over the place. While some of those models projected a 90-percent decrease in parking demand, others estimated that we would need more parking to accommodate the time AVs waited (likely idling) between rides.

Moreover, many of those researchers made optimistic assumptions about the percentage of people who would be willing to use robotaxis, and to share them with strangers going in the same direction.

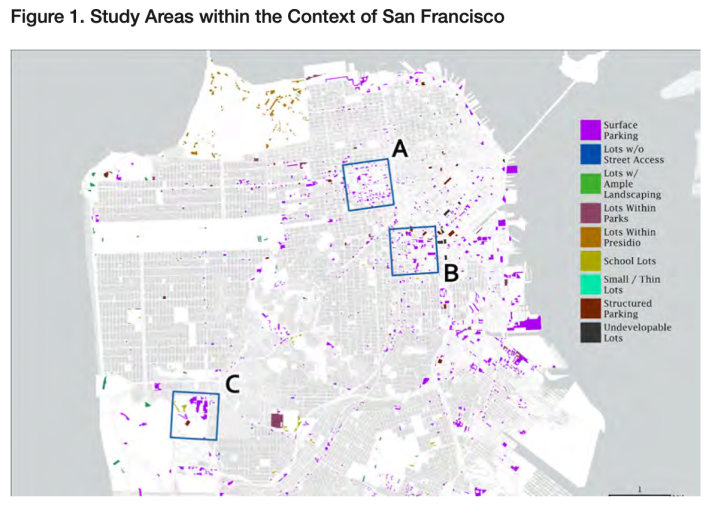

To settle the debate, at least one for city, Larco and his colleagues modeled the AV-saturated future of three neighborhoods in ultra-expensive San Francisco, a city with one of the highest incentives to locate more developable land for affordable housing. Rather than assuming that AVs would be a parking-reduction panacea, though, the researchers modeled a range of scenarios wherein the demand for car storage dropped by as little as 20 or as much as 80 percent — and asked tough questions about whether the specific parcels that drop in demand would free up would actually be redeveloped into an apartment building, based on existing market incentives, lot size, and other factors.

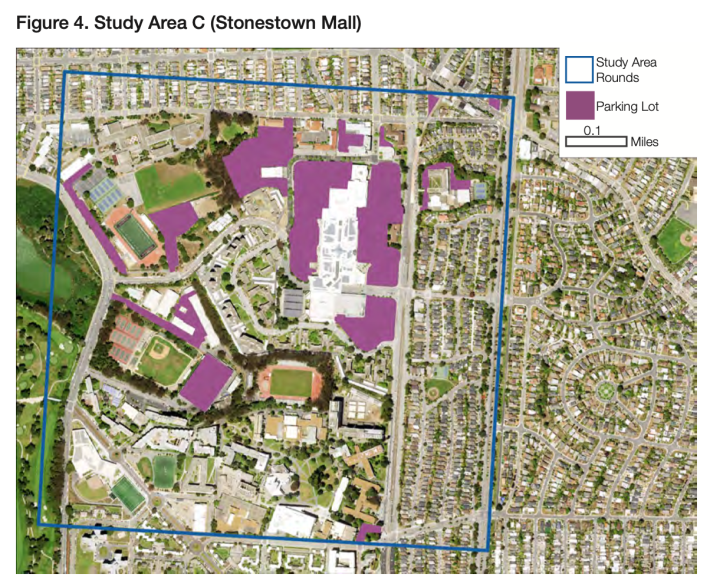

In the more car-dependent and less transit-connected Stonestown Mall region, meanwhile, a 40 percent dip in parking demand would generate 3,680 new housing units, with a 60-percent dip yielding 5,600 units or more. Achieving either milestone, though, would depend on a constellation of wildly ambitious scenarios occurring simultaneously, including virtually all AVs being shared rather than personally owned (something 54 percent of Americans say they won’t do) and most of those robotaxi rides being pooled rather than solo (also unlikely, considering only one-third of human taxi trips are shared in the handful of US cities that have embraced pooling the most — and in many cities, it’s as little as one-eighth).

Moreover, because it is geometrically impossible to run a robotaxi fleet without it, San Francisco would need to maintain a world-class transit system that tempts most residents not to take AVs at all — while simultaneously creating a dizzyingly comprehensive AV ecosystem that stretches all the way into the suburbs.

“If AVs only happen in San Francisco — well, most of the need for parking is for people coming from outside San Francisco,” Larco added. “And that’s true of most urban areas; it’s people coming from the periphery into the center who are the ones parking their cars. If you don’t have massive geographic penetration, the amount of reduction you’re going to see is going to be a lot smaller…and unless you can get your business model to work in the downtown core and in the suburbs, you’re not going to have that scale of deployment you need to put a real dent in parking. ”

Larco acknowledged that dense, transit-rich megacities like San Francisco aren’t the norm across America, and the Bay Area metropolis has already done the hard work of eliminating virtually all parking requirements. In expensive yet car-dominated communities like Los Angeles and Dallas, he suspects AVs would have a greater impact on reducing parking demand — though whether they will help or harm communities’ other goals is a separate question.

“We need to ask ourselves: is this technology solving a problem, or is it a solution in search of a problem?” he adds. “Will people refuse to use this thing, for any reason — because of ease, because of cost, because of culture? What are the use cases that align with the feasible business models? What are the cascading impacts on equity, the environment, health, the economy?”

And even if shared robotaxis do someday give residents of cities like San Francisco a new way to get to the airport or the office park, Larco wonders whether it will be worth the billions of dollars and decades of brainpower that have been invested into bringing that dream to life — especially when old-school options were there all along.

“That’s the question we don’t ask enough — will this innovative technology be the most efficient way to get to whatever benefit we’re seeking?” he adds. “Would a bike lane, or some other, more mundane mobility [improvement], maybe have made more sense?”