One Washington county’s decision to stop requiring cyclists to wear helmets by law was associated with an increase in helmet use, a new study finds — and that finding could have a major impact for advocates of equitable cycling legislation nationwide.

Improving safety for cyclists on the road should be a no-brainer. But when helmets are paired with legislation – and police action more specifically – it can get complicated.

Take King County, Washington, a cluster of cities and towns with an estimated 2.1 million residents, and one of the first and only cities to adopt legislation connected with helmet use back in 1993. In February of 2022, though, King County repealed a helmet requirement that many advocates say disproportionately targeted people of color and the unhoused. At the time, some critics opposed repealing the legislation because they were concerned that helmet use would decrease after abolishing the rule, resulting in a surge in cycling-related head injuries.

A recent study from Public Health Seattle and King County, though, may offer some good news — not just for Washington, but for advocates across the country trying to thread the needle between pushing for the benefits of wearing helmets on bikes and scooters, and managing overreaching helmet legislation that negatively impacts vulnerable communities.

So, what’s in the report?

The authors of the Seattle public health study emphasize that rescinding helmet laws was just one part of a long-range, multi-pronged strategy to improve cycling safety awareness and advocacy in the Washington community.

Back in 2004, the same agency conducted observations of 1,473 cyclists and recorded an 80 percent overall helmet use rate, which provided researchers a strong baseline for comparison in the 2022 report. Meanwhile, between April and September 2022, county officials gave out 1,875 free helmets across the county.

Many Washingtonians, apparently, were still wearing those helmets when the researchers counted again. Based on observations of over 2,000 bicycle and scooter riders at over 50 sites across the county, researchers observed a helmet use rate of 85 percent, up five percent from the 2004 report. For three key groups — children between five and 14, toddlers and infants under five years old, and cyclists who used their own personal bikes — that average was a staggering 91 percent.

In all cases, helmet usage had gone up since 2004 across all age categories, regardless of gender.

“It was really gratifying and pleasing for us to see that helmet use rate was was so high,” said Tony Gomez, who heads up the manager of Violence and Injury Prevention, for Public Health Seattle and Dr. Martin Luther King County.

Gomez stresses, though, that those results were likely due to decades of efforts to encourage cycling and helmet use, rather than the repeal alone. In another study released in 2019, years before the helmet law was taken off the books, researchers found that helmet use for riders of personally-owned bikes across parts of Seattle also hovered around 91 percent, though similar analyses were not conducted in other parts of King County.

He also notes that there’s still more work to be done: the number of rideshare cyclists and scooter riders wearing helmets was significantly lower than riders of personally-owned bikes, at 45 percent and nine percent, respectively.

Why does it matter?

Though the King County data is observational, it could go a long way towards assuaging residents’ fears that nixing helmet requirements might prove to be a deadly mistake — and it could also help open the door for more dialogue about eliminating pretextual stops that pose their own dangers to vulnerable communities.

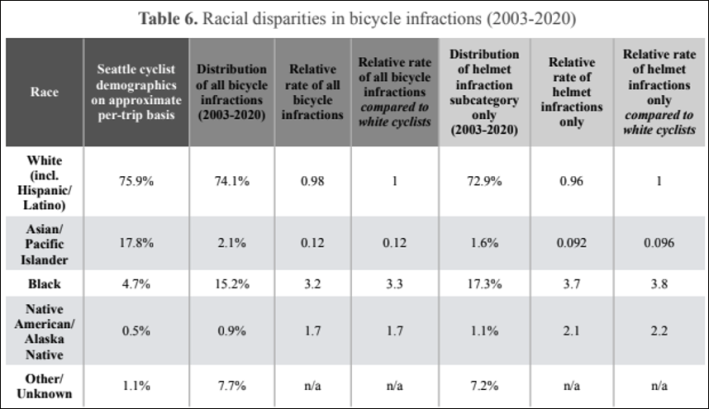

The helmet law repeal, after all, was made after two critical reports that revealed a disproportionate number of police stops among unhoused residents and people of color — a pattern of law enforcement overreach that’s all too common across the country.

Ethan C. Campbell, a University of Washington doctoral student who conducted the latter study, was not surprised to hear that helmet use had stayed high in King County, even after police stopped getting involved.

“It’s tremendously vindicating to see the results from the study,” Campbell said in a recent phone interview. “We have a culture of helmets here, and that is more powerful than anything else.”

And while helmet use is proven to reduce some injuries, Campbell said the focus for advocates has to address the systemic issues that make streets more dangerous for cyclists overall — including the dangers of police stops and car crashes, for which helmets provide little protection.

“There’s not a safe place for people to bike here,” Campbell said. “[It all comes down to] creating smarter, 21st century streets that are designed with safety in mind, instead of designed with the goal of just putting as many vehicles through as you can.”

George Kevin Jordan is a freelance writer based out of Washington, D.C.