Simply taking away the licenses of older drivers who show signs of dementia without addressing the dangers of the car-dependent communities in which they live may not deliver as many safety benefits as policymakers hope, a new study suggests — and it may spike the number of deaths among seniors who walk and bike, too.

As part of a new study published at the Journal of the America Geriatrics Society, researchers at Johns Hopkins University studied the impact of a 2012 Japanese law which required motorists over 75 to be routinely screened for cognitive impairments. In 2017, that law was amended so that law enforcement could use those medical results to revoke the licenses of people diagnosed with dementia and other conditions.

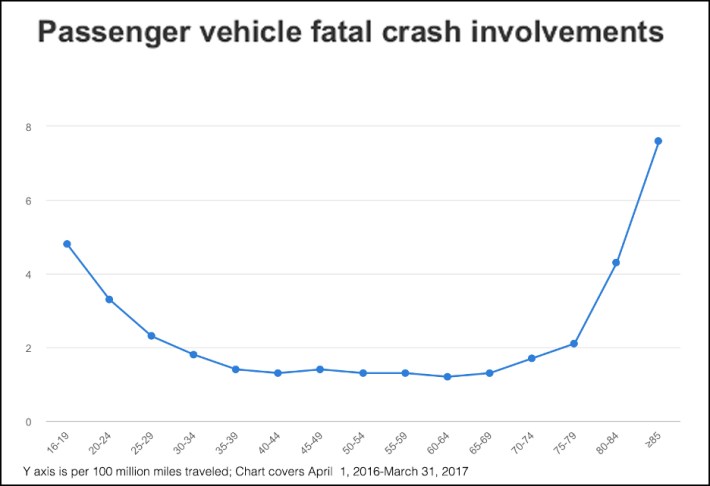

The policy was prompted, in part, by Japan's rapidly aging population, of which 29 percent were aged 65 or older in 2020 — the highest proportion of seniors reported in any country in the world, and a much bigger sample size than previous studies of cognitive screenings in other countries. In the U.S., by contrast, seniors made up just 16.8 percent of all residents, but in both countries, the oldest motorists on the road are disproportionately involved in fatal crashes — not necessarily because they're more likely to cause a collision than younger and more reckless drivers, but because aging bodies are less likely to survive a wreck when one happens.

Japan is home to a far greater proportion of transit-rich megacities than America, but the country also has its share of autocentric communities where taking away a senior's keys essentially means taking away their independence.

"In Tokyo, it’s okay not to drive; I don’t have a car, my parents don’t have a car, my brother doesn’t have a car," said researcher Haruhiko (Hal) Inada. "But in most areas of the country, just like the U.S., we do need a car to move around — and if older drivers give up their licenses, they are often no longer be able to live in their homes."

Inada acknowledges that in some ways, Japan's new law was a safety success. Between March 2017 and December 2019, the country recorded more than 3,600 fewer car crashes involving drivers over 75 than would have been expected over that period based on statistical trends, a decrease that was particularly notable among men, who made up 88 percent of the decline.

The researchers also noted, though, that 959 more elderly pedestrians and cyclists were involved in collisions after the license revocations started — and the ratio of who was impacted basically flipped, with women making up 83 percent of the additional vulnerable road user victims.

Inada also points out that those stats don't capture the cascading health problems that often follow when older people lose access to the only form of mobility available to them, including depression, social isolation, and further declines in their cognition. And he and his co-researchers aren't even persuaded that the crash declines can be solely attributed to the fact that a handful of unfit drivers were stripped of their driving privileges by the police — because thousands of others voluntarily surrendered their licenses over the same period.

In addition to 674 motorists who had their licenses revoked during first six months of the license revocation policy alone, Inada points out that nearly 30,000 others were flagged as potentially exhibiting cognitive impairments, but were allowed to keep driving — though many of them seemingly chose not to.

"We were suspicious [of this policy], and we still are," he added. "We personally think such a screening policy is not a great way to increase road safety among older people, partly because we’re still not sure if the suspension or revocation was the thing that brought about this safety benefit among drivers. We speculate that this is mostly because of the decreased number of older people behind the wheel."

Inada stresses that the study's results do not imply that drivers with severe dementia should be allowed to endanger others to avoid becoming victims of pedestrian crashes themselves. He does say, though, that policymakers should think holistically about ensuring that elders have access to other forms of mobility when their driving skills begin to wane — and use early screenings as an opportunity to ease the transition to a life without driving, rather than abruptly yanking licenses away.

He acknowledges, though, that those transitions will be harder in ultra car-dependent America — especially as the proportion of seniors continues to swell. The number of U.S. residents over 65 is projected to double over the next 40 years, but there aren't anywhere near enough walkable and transit-oriented homes to accommodate them all.

"I think this could be a bigger issue in the US, because there’s so much less public transport there," Inada adds. "Unless driving is fully automated, everyone, including us, will have to stop driving someday. We should prepare older drivers a lot before [that happens.]"