Blindspots the size of a pre-school classroom. Hulking curb weights. Tall, aggressive hoods that can easily strike a fully grown adult at the level of the neck.

Those are just a few of the design features common on American SUVs and pick-up trucks that experts suspect are driving the U.S. roadway death crisis as sales of megacars skyrocket. And some experts think there may be one more to add to the list: high-mounted headlights glaring straight into the eyes of other road users.

The problem has been the subject of little focused study to date, but researchers are increasingly sounding the alarm about the links among the rising popularity of the passenger vehicle class known as "light trucks," the increasing prevalence of glaring headlights on U.S. roads, and the role of vehicle illumination standards in the national traffic violence crisis.

According to one 1993 study, around 12 to 15 percent of car crash deaths were "caused by glare from the high-beam headlights of oncoming traffic at night" — and that was back when the bestselling Ford F150 sat five inches shorter than it does today, and long before new megacars outsold smaller vehicles three to one.

“Tall pickups and SUVs and short, small cars are simultaneously popular,” said Daniel Stern of Driving Vision News in a recent interview with the New York Times. “The eyes in the low car are going to get zapped hard by the lamps mounted up high on the SUV. or truck every time.”

It also has the potential to blind people outside cars, other experts say.

"Part of the problem is the way that headlights standards are defined," explains John Bullough, program director at the Light and Health Research Center at Mt. Sinai School of Medicine. "[Regulation] generally treats the headlight an isolated object that has no connection to the vehicle...But if the headlight is four feet off the ground, that changes things a lot. For someone in a sports car mounted lower to the ground, a lot of that bright area [emitted by a light truck] is going to land right where that other driver's eyes are going to be. The same thing is true of a child."

Of course, an SUV's higher, brighter headlights should theoretically have a big upside: illuminating pedestrians walking on roadsides and improving their safety in the dark, unlit conditions where 76 percent of pedestrian deaths occur. In particular, good-quality high beams — or as they're known throughout the rest of the world, simply "driving beams" – have a strong track record of preventing crashes with walkers.

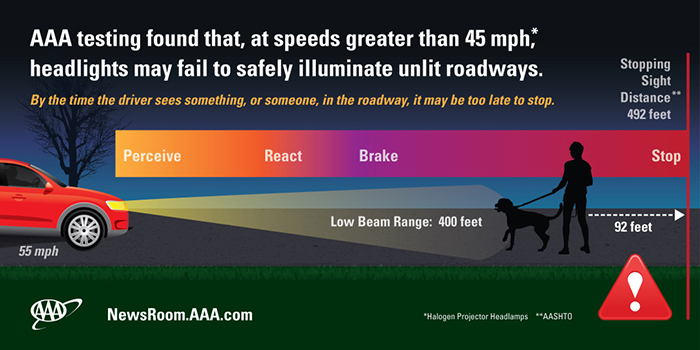

In practice, though, studies show that many drivers actually don't use their brightest lights most of the time, defaulting instead to far-weaker low beams — or as they're known elsewhere, "passing beams" or "fog lights" — to prevent blinding other motorists who might come around the next bend, even when they're driving alone on pitch-black roads. Add in the fact that low beam visibility plummets when drivers are going 45 miles per hour or more on unlit rights of way, and megacar headlights pack a dangerous double whammy: over-used low beams that aren't bright enough to see walkers on dark, fast roads, and high beams that sit so high on the vehicle that they stun basically everyone around them.

To complicate matters even more, the SUVfication of America isn't the only reason why so many road users are complaining about blinding lights. Bullough also points to the use of LED bulbs — which are critical for energy efficiency but also more painful to human eyes because they produce more harsh blue tones —as well the fact that headlights can easily become misaligned when drivers hit potholes or simply overload their trunks. Some states like Virginia require motorists to adjust their headlight alignment as part of routine vehicle inspections, but not all, and even a few degrees can make a huge difference.

To answer those concerns, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration issued a rule last year that will, for the first time, allow U.S. automakers to install Adaptive Driving Beam headlights that automatically dim the lights when there's an oncoming driver present, while leaving beams on high the rest of the time to make walkers and roadway hazards as visible as possible.

Unlike in other countries, though, the U.S. capped how bright those lights can get based on an archaic standard set in the 1970s, which some experts worry could limit their pedestrian-protecting potential — especially given that advanced technologies like automatic braking systems don't work well in low-light conditions at high speeds, even with their adaptive high beams on.

"Right now, the beneficiaries of these systems tend to be other drivers," added Bullough.

Bullough says that to really solve the light truck headlight problem, transportation officials should think beyond the automobile and focus on coordinating their vehicle lighting with their street lighting landscapes. In a slow-speed, well-lit urban contexts, he says, some experts believe even good headlights, which follow a drivers' horizontal line of sight, may "compete" with other light sources that shine from other angles, confusing motorists' eyes, minimizing contrast on pedestrians' bodies, and counter-intuitively, making roads less safe.

"So maybe it would be better if those headlights could be dimmed not just to low beams, but to a 'city' setting that’s really low," he said. "It obviously would need to be looked at very carefully. ... But in an ideal world, we’d think about all these systems together, not separately."

Of course, there's another way that U.S. cities could ideally break down silos and make megacar headlights safer for everyone: reducing the number of megacars that are on U.S. roads, period. And doing that should include not just stronger vehicle regulations, but by making it possible for more Americans to drive less often in the first place.