A staggering number of U.S. community college campuses are located miles from the nearest transit stop, a new report finds, and the distance puts critical educational opportunities firmly out of reach for students who can't or don't drive.

According to an analysis by the Civic Mapping Initiative, a full 43 percent of community and technical colleges have zero transit stops within a half a mile of their campuses, a distance the group says is generally considered to be a good basic threshold for walkability.

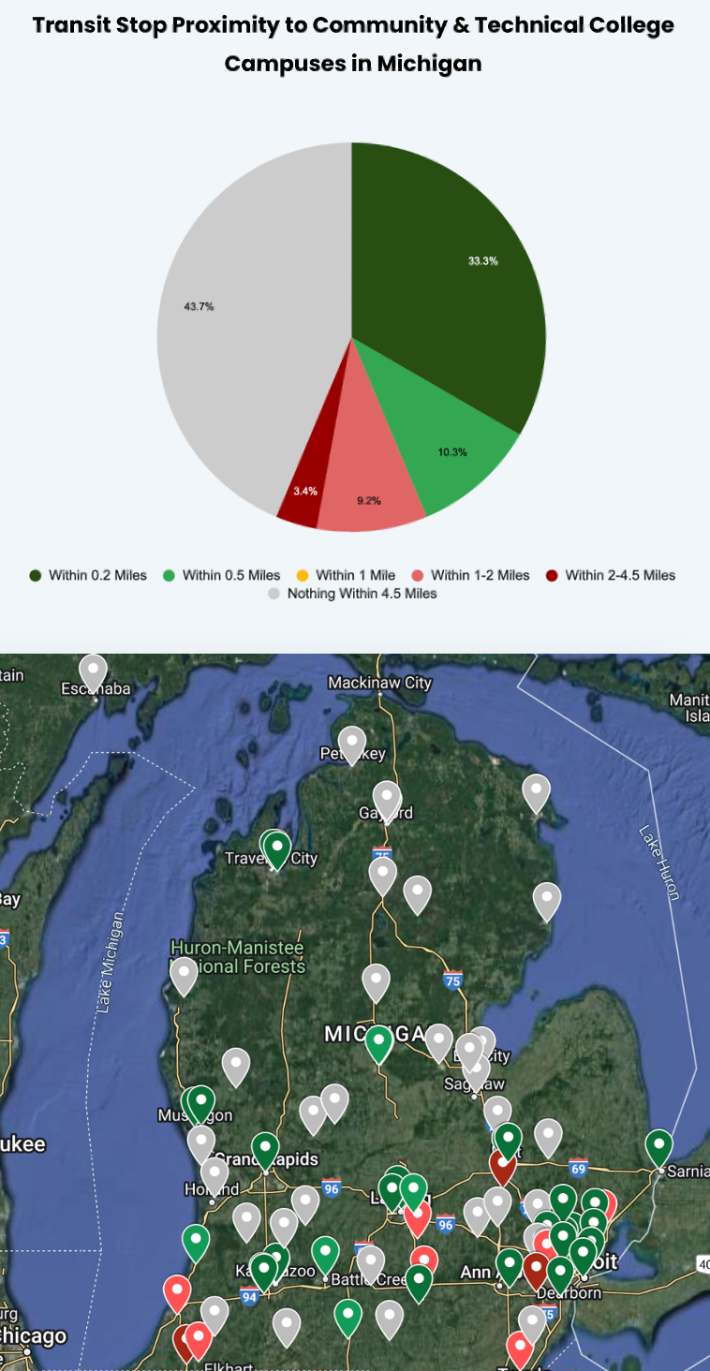

Those numbers are even more startling at the state level, which the group has recently begun mapping in more granular detail to spur local policymakers to take action. In Georgia, for instance, a stunning 72 percent of schools aren't easily accessible by bus or train – and of those schools, about 80 percent are a full 4.5 miles or more from the nearest station. Michigan isn't much better, with 66 percent of campuses located outside an easy walking distance of shared transportation, and Maine, where only half are.

Those numbers have massive implications for the whopping 58 percent of community college students who come from low-income backgrounds, for whom these schools often represent the only affordable higher education option available. Some experts estimate that obtaining an associate's degree increases the amount of money an American will make over the course of her lifetime by around $250,000 — and that without it, it can be virtually impossible to move up into the middle class.

"In higher education, we often talk about community college as an open door to building skills and getting on the path to economic security," said Abigail Seldin, co-founder of the Civic Mapping Initiative. "But something else we often say is that a lot of these students are just one flat tire away from dropping out."

Students at state-sponsored colleges aren't the only ones who benefit from creating reliable, shared routes to campus — and not just when it comes to America's roads or the climate at large. An analysis from urban economist Joe Cortright once found that having a high percentage of residents with a four-year degree is directly correlated with higher levels of community wealth, adding that "cities with poorly educated populations will find it difficult to raise living standards in a world where productivity and pay depend increasingly on knowledge."

var divElement = document.getElementById('viz1676659722290'); var vizElement = divElement.getElementsByTagName('object')[0]; vizElement.style.width='100%';vizElement.style.height=(divElement.offsetWidth*0.75)+'px'; var scriptElement = document.createElement('script'); scriptElement.src = 'https://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js'; vizElement.parentNode.insertBefore(scriptElement, vizElement);Cortright called it "the first, most important thing to remember about urban economic development in the 21st century."

"This is one of the reasons why Boston is richer than Wheeling, West Virginia," added Bill Moses, managing director of the education program at the Kresge Foundation, which is supporting the Civic Mapping Initiative's analysis. "When you build transit connections to community colleges, you’re putting people on a pathway to opportunity, rather than keeping them mired in neighborhoods they can’t easily leave without an automobile."

Moreover, both Moses and Seldin emphasize that simply getting students more access to automobiles won't necessarily solve their mobility challenges. Many schools and educational nonprofits do offer emergency aid funds to fix that "one flat tire," but those programs are too expensive to be widely scalable; federal student loans, meanwhile, can typically be used for car repairs — albeit at a steep premium after the interest comes due — but not to replace cars that are too damaged to be driven, or to supply a mobility-insecure student with a vehicle they don't already have.

"Low-income students typically come from families that may or may not have any car, and when they do, it often has to be used by the breadwinner," added Moses. "So they get to school on the bus all the way into June of senior year. But when they graduate, suddenly they don't have that anymore."

Even if a conveniently located stop is available, though, Seldin says that unlucky learners' mobility challenges may still not be over. Civic Mapping Initiative was only able to measure the straight-line distances between transit stops and academic buildings, but in reality, students may be forced to take a far longer route, not to mention navigating myriad other difficulties of navigating an underfunded transportation not always built with needs of the people who rely on it most in mind.

"In many ways, this is a best case scenario," said Seldin. "We can’t show how well these routes or schedules actually work for students — whether fares are affordable, whether stops are safe or whether they’re located across a multi-lane highway from the campus. It also can’t capture [the quality of] local paratransit, which a lot of students need. ... Our students are parents, workers, people living with disabilities. They have to manage time poverty while they juggle family, work and school commitments. It can all be really hard."

When transit agencies coordinate with campuses to meet their students unique needs, though, the effects can be amazing. Moses cites a program at the City University of New York that provides students with free, unlimited access to the city's world-class transit system, and has been credited in part with improving the amount of time students remain in school, as well as their graduation rates.

Sometimes, it can even turn them into lifelong straphangers.

"One of the best ways to get people riding transit is to take people who are 18 or 19 and just getting them int he habit of taking a bus or a metro," he adds. "Eventually, a lot of them will say, 'I don’t need a car.'"

This is a great way to ease students into riding public transit.

— Muhammad Tarek Alameldin (@Muhammad_Speaks) February 26, 2020

My free transit pass at Sacramento Community College led me to start riding transit frequently.

Now, 5 years later, I don't even own a car anymore. https://t.co/2WAlQOUom2

Even outside of transit-rich New York, though, connecting campuses to frequent, high-quality transit with good walking connections isn't just possible — it's often low-hanging fruit. The Civic Mapping Initiative has found that an additional 25 percent of community colleges could be made accessible simply by extending existing routes. And when building a whole new route to campus is necessary, a bipartisan group of senators and congresspeople have even introduced legislation, the PATH to College Act, to give agencies dedicated money to do it, in addition to the millions of dollars in general funds available to agencies under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the Inflation Reduction Act, and the American Rescue Plan.

Even if that doesn't happen, though, Seldin says the schools can make a difference simply by cultivating "direct relationships between the campus and the transit agency" to encourage better service, negotiate fare discounts for the college community, and literally bring higher education within reach.

"Transit solutions are enduring," Seldin adds. "Each day, hundreds of people come and go from these campuses. Connecting them more closely to their communities has so many benefits beyond an individual student’s ability to attain a degree."