Many motorists yield to pedestrians in crosswalks — but not when they're driving at deadly speeds, according to a new study that shows the need to slow down car drivers with broader road design changes, and not just more signs and paint.

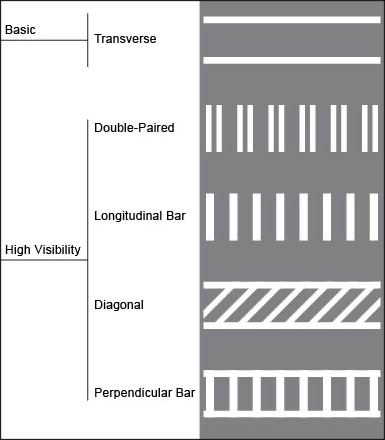

As part of a recent experiment conducted during more than 1,200 crossing attempts at intersections across four states, transportation professionals at Kittleson & Associates found that 75 percent of U.S. motorists will yield to a walker in a "basic" crosswalk, which is what engineers call intersections marked with nothing more than two parallel lines of white paint.

That was only true, though, when drivers were traveling at 20 miles per hour — a speed at which traffic rarely moves on auto-centric U.S. streets. Once motorists reached 30 miles per hour, just one in eight of them yielded to the walker in those same intersections. And when streets were outfitted with "high visibility" crosswalks instead, still only one in four of the faster drivers let pedestrians pass.

Kittleson's pedestrians, of course, were actually trained researchers who were instructed not to enter the crosswalk if a driver didn't stop for them, so none of those failures to yield resulted in an actual collision. The firm points out that in real life, though, those differences in speed "can mean the difference between life and death”: studies have shown that the average pedestrian struck by a driver traveling 20 miles per hour will survive about 90 percent of the time, while only 40 percent will survive if they're struck by someone doing 30.

That percentage can get even smaller for pedestrians who are very young or old, have certain disabilities, or are struck by particularly large cars like pick-up trucks and SUVs.

The Kittleson researchers were careful to note that their study did not discredit the importance of designing crosswalks so drivers can easily see them, at least in places where the Manual of Uniform Traffic Devices advises that they should be painted at all (and in many cases, it doesn't). Even the best-designed crosswalk, though, isn't a foolproof magical force-field — and its pedestrian-protecting powers do wear off as drivers speed up.

"If an uncontrolled crosswalk is worth marking, it appears to be worth marking with a [high visibility crosswalk] design. ... [But] HVCs alone are not enough on their own to ensure yielding when people are driving at high speeds," they wrote.

It's also important to note that Kittleston's experiments were only conducted at intersections with relatively low speed limits of 35 miles per hour or less, on roads with no more than two lanes in each direction and no stop signs or signals, among other factors designed to help the study authors zero in on the specific impacts of crosswalk design alone.

On more complex roads — particularly the high-speed, multi-lane arterials where pedestrian deaths overwhelmingly happen — planner Warren J. Wells hypothesizes that crosswalk "yield rates ... are no doubt much lower."

Wells emphasizes, though, that the Kittleson researchers' findings should send a clear message to transportation leaders who might wonder why motorists fail to let walkers pass safely even at a shiny new zebra crossing on a too-fast road — or worse, assume that some drivers will just always be jerks, and walkers should simply stay out of their way.

"The answer is not to add expensive signals to every crosswalk, or to prohibit pedestrians from crossing away from signals," he wrote. "The answer, as always, is to slow down the cars."

Editor's note: an early version of this article misstated the terms of the experiment. It occurred during 1,200 crossing attempts, not at 1,200 intersections.