The sky-high gas prices that dominated last year's news cycle amounted to just 36 more cents a day in fuel costs to the average American — and it didn't deter them from driving more than the year prior, a new report finds.

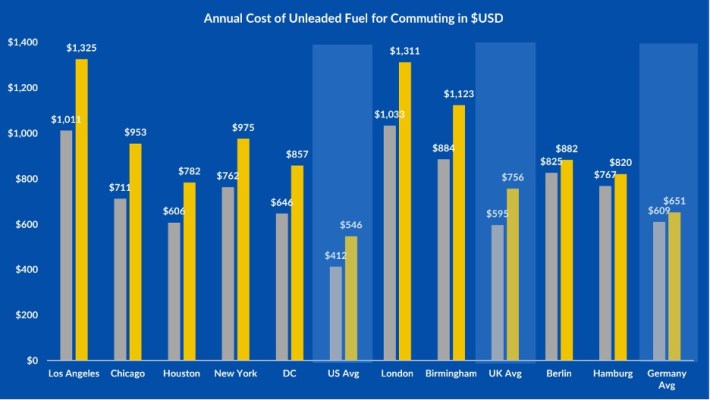

According to the annual Global Traffic Scorecard from the top transportation analytics firm INRIX, U.S. commuters spent about $546 in annual fuel costs during 2022 — a 32-percent spike compared to last year, but just over half the price of a postage stamp per day on average. In notoriously expensive Los Angeles, meanwhile, fuel costs rose from $1,011 to $1,325, narrowly beating out London for the most expensive commute in the world, but still clocking in at about 86 extra cents a day.

Even if that leap still seems large, it wasn't big enough to discourage Americans from driving. INRIX's data showed that nationally, vehicle miles traveled remained essentially flat compared to last year, and remain just nine percentage points shy of its pre-pandemic peak.

"This data shows that in general, gas prices are relatively inelastic," said Bob Pishue, transportation analyst for the firm. "Unless there’s a really steep psychological barrier like, say, $8 a gallon, increasing the price of fuel is not likely to result in a large decrease in driving. People treat it more like their electric bill; you can turn the appliances on or off, but absent something big, like getting solar panels, at the end of the day, you just have to pay it."

If last year's countless "pain at the pump" headlines are any indication, though, those numbers will be met with far more public consternation than a monthly electric bill — not least in Washington, where gas prices have long been treated as a powerful bellwether for voters, or, to quote a recent Politico headline, the "one problem that rules them all." The revelation may well be followed by yet another proposed gas tax holiday, or calls to build more lanes so drivers don't waste precious gas idling in traffic (even though we know that doesn't work), or a push to increase access to electric vehicles for low-income people for whom fuel prices represent the highest proportion of household income.

Even among American families who legitimately can't afford that extra 36 cents a day — and to be clear, those families exist, and they matter — some advocates say that the better way to make transportation less expensive would be to prioritize policies that make not driving possible for a larger share of more household trips.

INRIX's annual statistics, though, are rarely interpreted that way by media outlets and policymakers.

"We all know the story we’ll see after this report comes out; it'll be state DOTs [spotting] their communities on the list and saying, 'Look at all this money we’re losing; we need to widen this roadway!'" said urban economist Joe Cortright, founder of the think tank and website City Observatory. "It’s just a way to propagandize for these highway projects."

Cortright, who's been critical of the transportation impacts of INRIX's scorecard for years, says that gas price spikes need to be seen in a larger context, particularly before policymakers react by making big changes that could make the problems of car dependency worse. Despite nail-biting in Washington, he says the new data suggests Americans seemingly trusted that fuel price spike would be temporary, in sharp contrast to the financial crisis of the late 2010s, when prices rose steadily and SUV sales dove in response.

"Transitory changes in prices are less important than permanent ones," he explained. "There's a lot of evidence that people tend to just weather [these changes] in the short term; they don’t change their travel or saving behavior that much. ... I think people just held their breath through the beginning of the Ukraine invasion and waited for prices to come down, and they did."

He also adds that by now, many more Americans are priced out of neighborhoods where not driving is a realistic possibility, which remain in scarce supply — and like Pishue suggests, they simply have no choice but to keep paying their automotive gas bill like any other utility.

"Basically our entire landscape, particularly the suburbs, is predicated on cheap gasoline," Cortright added. "It’s part of the fabric. That can change, and we’ve seen that change in many places the last 20 years or so. But it's a longer-term process."

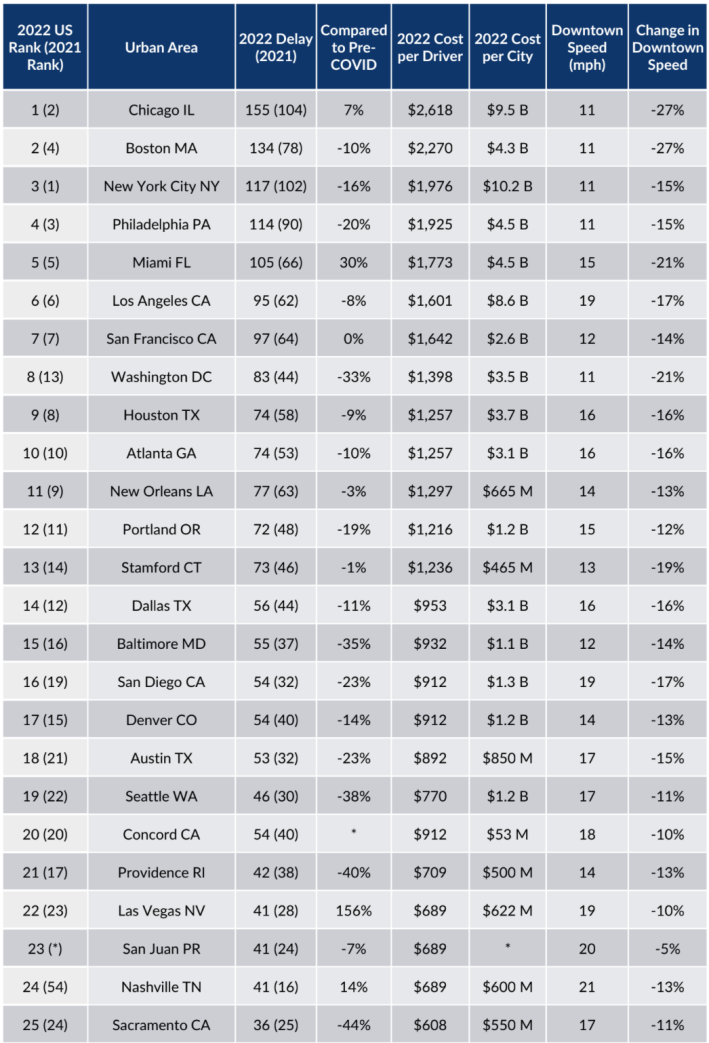

Cortright has other issues with the framing of INRIX's report, not least its finding that American motorists "lost" 51 additional hours sitting in traffic jams in in 2022 compared to the prior year, at an estimated (and in the opinion of some pundits, largely imaginary) national cost of $81 billion in 2022 alone. The new report doesn't specify what, exactly, transportation leaders should do to restore those stolen hours or the money associated with it to the U.S. public, though he wishes it were more explicit about what doesn't work: building endless road capacity.

"Everybody complains about congestion; well, why do we have congestion?" Cortright adds. "It’s because we don’t price roads correctly, so people over-consume them. It shouldn't surprise us that there's a long line in front of Ben and Jerry's on Free Cone Day; you’re not charging anyone enough for ice cream."

He also says INRIX's own data suggests a better alternative to curing traffic jams — though they'll have to look back to a historic drop in driving and congestion in 2020 to find it.

"[Quarantine] was an unprecedented experiment in how the transportation system works," he said. "What INRIX’s data shows is that when travel demand went down, congestion dropped dramatically — about twice as fast as travel. If we actually had some demand management strategies, we could reduce congestion."

Cortright adds that properly pricing gasoline to reflect its real costs to society isn't the only way to manage demand for car travel; congestion pricing, parking reform, curb management, and a universe of other strategies can all play a role, too. The question is whether reporters and policymakers will seek out those strategies.