When Shelley Bontje took her driver's license exam for the first time, she failed — and so did almost everyone she knows.

"My brother is really into cars, and even he didn’t get it on his first go," she added. "If you make one major mistake, you’re done. ... But I would say, in the end, that we're really good drivers."

That notorious test was the Dutch rijexamen, which is known for being one of the hardest in the world — though it doesn't get much press overseas.

Even as Holland has become globally famous for its people-first infrastructure, transportation professionals like Bontje, who works at the Dutch Cycling Embassy, have noticed that U.S. advocates rarely talk about the arduous process Netherlanders must undertake before they're allowed to drive, or how education contributes to her country's eye-popping safety stats. The per-capita road fatality rate in Holland has been roughly one-third of America's for decades.

Bontje said that much of that success can be credited to great road design, but that the nation's driving schools deserve some credit, too.

"How can you expect people with no education on a topic at all to behave properly?" she added.

Of course, getting a driver's license isn't totally impossible in Holland — indeed, 80 percent of Dutch adults will eventually get one, compared to 89 percent of Americans — and on paper, passing muster at a Dutch DMV doesn't seem too daunting.

According to local driving schools, about 48 percent of test-takers in the Netherlands will fail either their written or on-road test in a given year, which is roughly on par with states like Arkansas (47 percent) and Oregon (46 percent). Notably, neither U.S. community nor Holland actually require would-be drivers to take a formal driver's education course — even though Oregon officials note that 91 percent of teens involved in crashes didn't take one.

Experts say, though, that not hitting the books is pretty rare among Dutch drivers because "without driving lessons it is virtually impossible to pass the driving test," as the country's Institute for Road Safety research notes. And even with an average of 42 practice hours behind the wheel and thousands of Euros worth of study sessions with a professional instructor who has to go through a rigorous certification process of her own, many still struggle to succeed.

"Most people really need to study for it," added Bontje. "You won’t pass without studying unless you’re some kind of an Einstein-type."

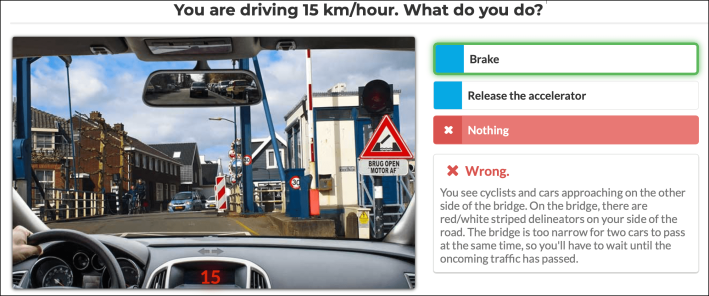

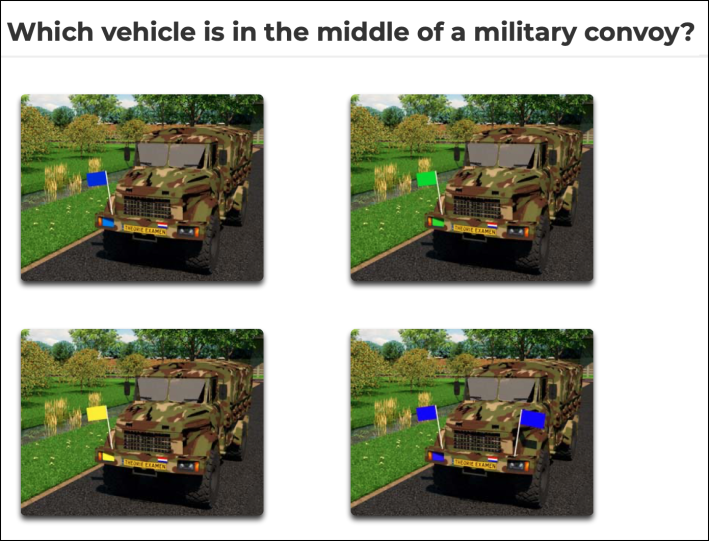

An English translation of a sample test question, via TheorieExamen.NL

The first ingredient that makes Holland's driver's licensing program so successful, though, is simply making young drivers wait a little while. Even the smartest baby Einstein can't take the notorious theorie-examen, or off-road "theory" test, until she turns 16, and when she does, she'll have to answer 65 challenging questions about virtually anything she'll encounter on the road. (Washington state, which some studies say has the hardest test in the country, has 40 questions, while many states have just 20 or 25.)

The test begins with a timed "hazard recognition" section during which students have just eight seconds per question to assess a photo of a complex roadway environment and indicate how they'd behave in response. Nearly every image is full of easy-to-miss but critical details, like a pedestrian emerging from between two parked cars, or a soccer ball in the middle of the road, suggesting that a child might be following close behind.

That's followed by "knowledge" and "insight" sections, which resemble the kind of multiple-choice tests with which most American license-seekers — except way harder.

Would-be drivers have to answer a randomized selection of forty questions from a pool of more than 1,500 possible prompts, including both typical prompts ("when should you use your low-beams?") and hyper-arcane details, like the maximum length of a tow rope, or whether a Segway is classified as a motor vehicle. Test-takers might be denied a license for not knowing whether their cars' heating or air conditioning uses more fuel, or what to do if their vehicle becomes submerged in a lake, or why the design of a sleepy rural road might induce "polderblindness," or zoning out behind the wheel.

If they just miss three of the twelve "knowledge" questions, they'll fail; if they miss four of the 28 "insight" questions, that's a fail, too. Put another way: every single driver on the road in the Netherlands scored a B+ or better on her written test.

This journalist, who passed her U.S. exam with flying colors, failed three practice tests before she gave up.

Even if he conquers the dreaded written exam, though, a Dutch teenager still can't even touch a steering wheel until he turns 16 and a half — and even then, he can only drive with a registered "coach" in the passenger's seat. And when he finally does get to take his road test at the ripe old age of 17, our would-be driver still might fail, because many examiners have such sky-high standards.

As one ex-pat laments:

"You can fail the test for driving too slow or too fast, for being ‘not confident enough‘ or ‘overconfident‘. You simply can’t win this game. An experienced driver from the US recalls that the first time he failed for ‘being too sure of himself‘, the second time for giving a way to a mom biking with two kids, and the third time the examiner asked: 'Why did you fail the first two times?' before announcing that he failed again."

And even if he doesn't fail, our novice motorist still can't drive unsupervised — because that privilege is only afforded to 18 year olds, an age at which most U.S. teenagers have held an unrestricted license for a full two years.

Experts, though, have long questioned the wisdom of giving driving privileges to children with still-developing brains and even less on-road experience. The Insurance Institute for Highway estimates that simply moving South Dakota's licensing age from 14 and a half years old — the lowest in the nation — to 17, fatal crashes among teenagers would plunge by 30 percent, even if no other graduated licensing requirements were instituted.

Bontje emphasizes that Holland's ultra-hard licensing exam isn't the only reason why it's such a safety standout, and that even the worst drivers are regularly stopped from causing harm by the country's profusion of "self-enforcing" infrastructure, like protected bike lanes. Even the best streets, though, can still require a little explaining – if only to hammer home why driving safely is so important.

"Self-explanatory infrastructure is essential," Bontje adds. "But when you’re in a car, you can always be a danger to others. That’s where education comes in."

And when a Hollander simply can't pass her test, it's often not the out-and-out disaster that might be for a car-dependent American. Bontje points out that all Dutch drivers over 75 are required to be examined by doctor to assess their fitness to drive — and, sometimes, pass the arduous exam all over again — but if they don't, they can often still live a healthy, independent life without a car, because the country's transportation network, though still imperfect, offers them options.

"You still feel this sentimental idea of, 'I’m losing my freedom,'" she said. "But at the other end, of course, there are way more alternatives to get around — by bike, by public transport, or walking ... There are people who will never have a drivers license at all, and they're thriving."

Editor's note: This article originally referred to the Dutch Cycling Embassy as the Dutch Cycling Federation. It has been edited to correct the error.