A pair of new studies are challenging the myth that micromobility doesn't cut car travel or reduce more emissions than the modes they tend to replace.

First, a recap: in recent weeks, two unrelated teams of researchers leveraged real-world scooter and e-bike data to better understand whether micro-mobile modes are helping cities achieve some of their most urgent goals, like reducing greenhouse gases and cutting congestion.

The first study, conducted by academics at the Georgia Institute of Technology, found that travel times in Atlanta swelled an estimated 9 to 11 percent as a result of the city's controversial 2019 decision to ban the modes after dark after drivers killed four riders. That modest effect became more pronounced during large events like soccer matches, during which drivers' commute times increased an estimated 37 percent and city streets were clogged with avoidable game-day traffic.

Interesting data from Atlanta. They banned scooter use at night and congestion increased making the average trip 10% longer. If You're worried the upcoming economic boom will result in bad traffic here in Syracuse the answer is more bikes and scooters! https://t.co/pBDiS7fiUq

— Turbo Bocce (@turbobocce) November 1, 2022

In the second report, analysts at the Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research in Germany were commissioned by micromobility outfit Lime to update a series of earlier studies about the carbon impacts of their vehicles — studies that Lime says have become outdated as the industry has rapidly evolved. While first-generation scooters notoriously lasted just a few weeks before they were too damaged to ride and had to be thrown away, experts say today's last about two years, and their life cycle emissions are 70 percent lower when analyzed from cradle to grave.

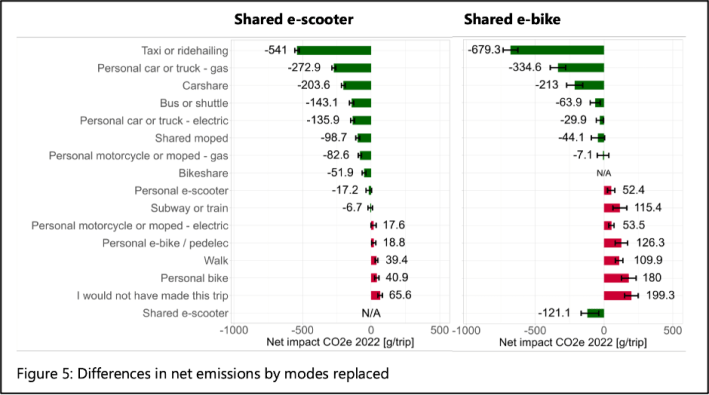

In the six global cities for which Lime provided ridership and survey data (including Seattle), the German analysts applied the same methodology as previous researchers and found that greenhouse gases actually decreased as a result of shared scooter and e-bike adoption. That's even accounting for the fact that some of those riders said they wouldn't have made those trips at all if Lime wasn't available — as well as the fact that others admitted to trading a comparatively greener walking, transit, or non-electric bike journey for a ride on an electric-assist mode.

Taken together, Lime says the two studies are proof positive that cities are underestimating how critical micromobility is to their residents — and their collective climate future.

"What's remarkable here is the speed with which the micromobility industry has been able to address the concerns that its introduction created," said Shari Shapiro, Lime's head of global policy. "Things that the car industry has been working on for decades – like reducing carbon emissions – as well as things that cities have been working on for decades – like getting people onto sustainable modes of travel – the micromobility industry has been able to accomplish in an incredibly short amount of time."

Some advocates, though, say both studies deserve some asterisks.

Vice News argued that the Atlanta results may not apply to the entire country, partly because the Big Peach only had a handful of major sporting events during the study period — and because the average travel delay time only amounted to a few minutes per driver. (Vice's reporter Aaron Gordon did note, though, that it was "a good study that will be cited by academics in the future and worth the time and energy he and his research team put into it," even if it provided "few definitive answers to urban transportation questions.")

Meanwhile, the German study, it must be restated, was funded by Lime itself, even though the authors do offer enough criticisms of the company to suggest they're being somewhat objective. The authors point out, for instance, that the micromobility industry could stand to keep fleets on the road even longer, and that they should continue to decarbonize the dirty mineral extraction process that the electric vehicle battery industry in general has struggled to avoid.

Relying exclusively on Lime's data also means, of course, that other micromobility companies' ridership and mode-shift stats weren't included in the study at all. Put another way: even if this particular company is, in fact, a good steward of the environment, that doesn't mean that all its competitors are, or that other companies' riders are forgoing enough high-polluting taxi trips in favor of scooter rides to make up for potential emissions increases when they trade a short walk to the store for a scoot. (That's what the researchers say happened in Seattle, which "shows the highest share of replaced walking trips, [though] it also has the highest share of replaced ride-hailing trips," noting further that "the substantial emissions reductions due to ridehailing replacement is sufficient to tip the scales despite the large walking replacement.")

And of course, the study can't account for the ways that poorly-parked scooters might limit the mobility of people who can't ride them, a concern that' been consistently raised by advocates for the disability community.

Still, Shapiro says the new research should prompt a conversation about why cities tolerate rather than celebrate micro-mobility modes — if they're not outright barring e-bikes and scooters from their streets.

Atlanta is just one of dozens of cities that have instituted scooter curfews, neighborhood-wide bans, or even rescinded the permits of micromobility providers entirely when people get hurt riding their vehicles — even if the reasons they got hurt had more to do with dangerous driving and deadly streets with no safe places for people to ride, rather than light electric vehicles themselves.

"I have a lot of sympathy for the cities; they're using leeches because they don’t have access to antibiotics," Shapiro said. "They’re often hamstrung when it comes to taxing cars or limiting car speeds, and building bike infrastructure can be really hard. But they do have authority, for the most part, over micromobility — so they use that authority to over-regulate our industry, even though it’s often unrelated to the underlying challenge."

Shapiro also emphasizes that neither of the studies capture some of the more intangible benefits of micromobility, which tend to get lost in broad metrics about carbon emissions and congestion levels. Because even if a scooter trip does replace a walking trip, that doesn't meant that it didn't make someone feel safer getting home from a bus stop at night — and in the long run, give her a clean alternative to the park-and-ride.

"We get a significant amount of pushback whenever our mode shift numbers show that scooters are taking rides away from [other forms of sustainable transportation]," she added. "But when you're looking at neighborhoods that aren’t well served by those modes, or you’re looking at people who would rather, for any number of reasons, take a scooter – even just not having to take two buses – well, that gives us a very different picture."