This article is a part of our annual Highway Boondoggles series, in partnership with U.S. PIRG. This series will explore some of the worst planned highway projects across the country, and explore why they deserve to be cancelled — and why U.S. transportation policy must be reformed to discourage similar initiatives in the future.

Learn more about yesterday's featured boondoggle in Maryland, and don't forget to check back for detailed analysis on the seven boondoggles that made this year’s list. You can also view the full report now.

Brent Spence Bridge

Cost: $2.8 billion

Opened in 1963, the Brent Spence Bridge carries Interstates 71 and 75 across the Ohio River between Covington, Ky., and Cincinnati. Notoriously congested, the bridge carries upwards of 160,000 vehicles every day — twice the number it was designed to handle. It is also a vital north-south trade corridor, and — due in part to increased traffic volume and the conversion of the bridge’s emergency shoulders into additional lanes in an unsuccessful attempt to mitigate it — a dangerous one: the Ohio Department of Transportation estimates that drivers are up to five times more likely to have a crash along the 7.8-mile Brent Spence Bridge corridor than on any other section of the interstate systems in Ohio or Kentucky.

The bridge has been beset with safety issues for decades, so badly in need of improvements and repair that it has become a poster child for America’s aging transportation infrastructure. While officials maintain that it is “structurally sound,” the Federal Highway Administration deems the bridge “functionally obsolete” due to its inability to cope with the volume of traffic it currently carries.

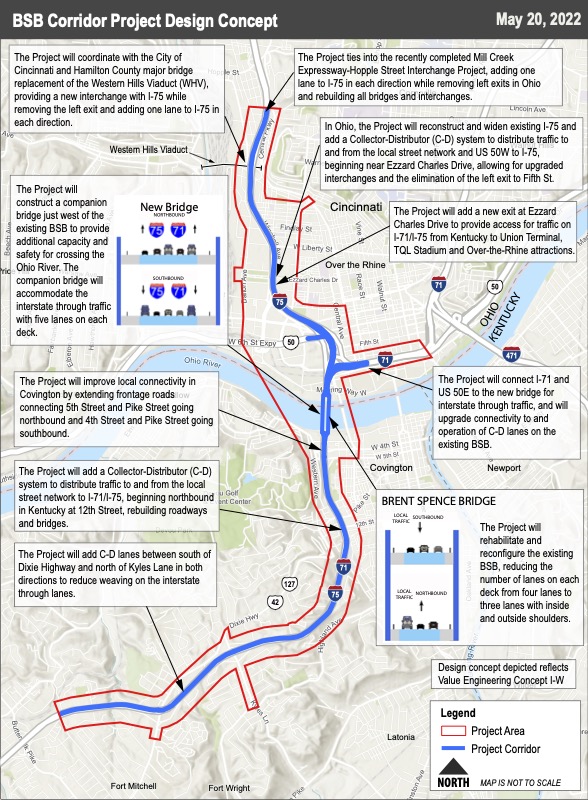

Development of alternatives for the bridge began in October 2004, initially led by the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet, and since November that year, by the Ohio DOT. In 2012, a preferred alternative was agreed to: build another bridge next to the existing one.

The Brent Spence corridor project is currently slated to cost a total of $2.8 billion, to be shared by the two states. One of the main barriers preventing the states from moving forward with the new bridge has been protracted wrangling over where this funding should come from. Northern Kentucky lawmakers refused to raise revenue through a toll on drivers. With the possibility of federal funding, however, the agencies now hope to be able to circumvent the tolling issue altogether and fund construction entirely from a combination of federal, state and local tax dollars rather than contributions from the drivers who use it.

In February 2022, Kentucky Go. Andy Beshear and Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine announced a joint request 0f up to $2 billion in federal funds for the project with the states themselves shouldering the remainder. In May, officials announced that they had applied for $1.66 billion through the Multimodal Projects Discretionary Grant program established by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. These funds would cover around 60 percent of the project’s total cost, with the remainder split across the two states: Kentucky contributing $572 million ($441 million from state sources and $131 million in federal funds) and Ohio providing $539 million ($303 million from state funds, using fuel tax dollars and state highway bonds, and $236 million from the federal government).

If this grant funding is received — the states expect to find out by the fall of 2023 — construction of the new bridge and upgrades to the existing one and the interstate network throughout the corridor are expected to begin within 18 months.

The new bridge, to be built just west of the existing one, will accommodate interstate through traffic with five lanes on each deck, with local traffic intended to remain on the existing bridge. Elsewhere, construction will include major bridge replacement, a new interchange with I-75 and the addition of a new lane to I-75 in each direction, and, in Ohio, the reconstruction and widening of the existing I-75 and the addition of new infrastructure to distribute traffic to and from the local street network and US 50W to I-75.

The “companion bridge” remains the preferred alternative because, the agencies say, “the goal … remains unchanged” — that is, “to improve safety and ease congestion by providing additional capacity that separates local and through traffic.”

“The preferred alternative … meets that objective.”

Except it doesn’t. While increasing vehicle capacity by 125 percent (the current bridge has four lanes of travel in each direction, the new structure adds another five in each direction), this is unlikely to have any meaningful impact on congestion. Congestion along the Brent Spence Bridge corridor is not the result of too few lanes, but of the layout of the region’s overall traffic network.

“The way Cincinnati is laid out, the more lanes you build on 75, the more traffic you draw," Stefan Spinosa – ODOT’s own Brent Spence project manager at the time – explained in 2015. "We could continue to build lanes on 75 but they would fill because of the nature of the traffic network in the region.”

Spinosa notes that future demand can realistically only be addressed through “a mass transit component.” The final plans for the Brent Spence project that Ohio DOT released in May do not appear to include any high-capacity transit component.

The project's likely failure to achieve its aim of easing congestion is not the only reason for skepticism over the Brent Spence Corridor plans. In its 2021 objections to the project, the Covington Board of Commissioners argued that as well as being “far too big for what’s needed” and requiring “billions in additional investment,” the scale of the then-proposed solution is “hugely disproportionate to our community and … not only hurts our businesses and residents, but interferes with our economic growth and that of the entire Northern Kentucky region.

“I-75 did immense damage to Covington,” the letter concludes. “This makes it far worse.”

While certainly in need of maintenance, the Brent Spence Bridge remains structurally sound. Describing it as “functionally obsolete” simply means it currently carries more traffic than it was originally designed to carry. But the laws of induced demand apply here as much as they do any other freeway-widening project, and, as with any other project, are likely to result in congestion at least as bad as before, and possibly worse, just with larger traffic volumes occupying more lanes.

A 2022 analysis by the urban development nonprofit Strong Towns concludes that, based on past experience, this project will likely “harm urban Cincinnati land values, frustrate attempts to repopulate the city center, promote further job dispersion and residential sprawl into Northern Kentucky, worsen automobile traffic in [Cincinnati], exacerbate pedestrian safety issues, misallocate infrastructure investment that could be better used for improving public transit, and worsen regional air quality, along with other environmental harms.”

One alternative, Strong Towns suggests, is to impose tolls on drivers using the bridge and use those funds for improving the quality and efficiency of public transit – including expanding streetcar service to the University of Cincinnati and across the river into Newport-Covington – and paying for cycling and pedestrian safety initiatives. “City and regional officials,” the analysis concludes, “should evaluate the post-toll traffic situation before committing billions of dollars to a project of dubious value.”