Artificial intelligence-equipped cameras can help protect children as they get on and off the bus — but only in cities that allow school districts to install the life-saving technology.

According to machine learning company Hayden AI, which is developing a new stop arm camera technology in partnership with Conduent Transportation, less than half of states currently allow their districts to use technology that captures images of drivers who illegally pass school buses when children are boarding or de-boarding a bus with its retractable stop sign extended, and automatically transfers information about the violation to law enforcement.

Of the 24 states where stop-arm cameras are legal, roughly 12 have actually implemented them, and only a handful of others, like Minnesota, are experimenting with the technology despite not having a stop arm law on the books. That's despite the fact that passing a school bus with its stop arm extended is illegal everywhere, and that surveys of U.S. school bus drivers suggest that more than 17 million violations happen every single year.

"This is a problem that exists a lot more than people think," said Charley Territo, a spokesperson for Hayden AI. "The collisions don't always make the front page news, and the near-misses certainly don't. But the results are often deadly."

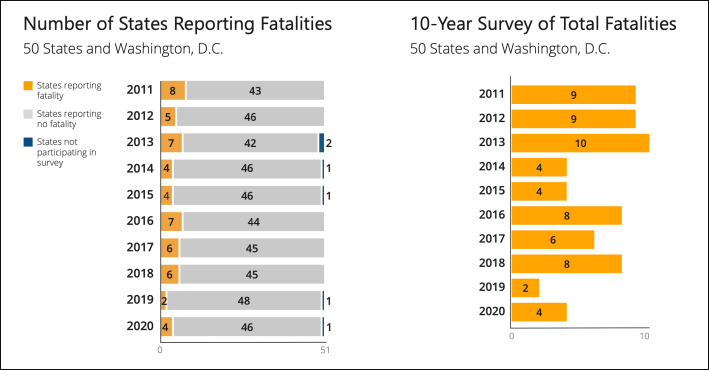

At an average of 6.8 deaths a year, school-bus-passing drivers claim the lives of only a small fraction of the roughly 380 pedestrians under 18 who die on U.S. roads annually. Territo emphasizes, though, that even one of these deaths is unacceptable — particularly when technology to deter drivers from making dangerous passing maneuvers is well within reach.

"It makes no sense to wait until there’s a tragedy to enforce an existing law," he added. "Just because tragedies haven't occurred in a specific jurisdiction doesn’t mean they won’t. Ask any school bus driver if this is a concern, and they will tell you it’s at the top of their list."

Hayden AI says that their tech "will be funded through fines and can be implemented without upfront costs to school districts or schools," making the tech essentially free to operate — at least as long as drivers keep breaking the law. Other AI-powered stop-arm camera companies claim that their technology reduces violations "30 percent year over year," and that 98 percent of drivers who get a ticket from the program never get a second one.

Stop arm cameras are not without controversy.

Much like other forms of automated enforcement, some advocates have questioned the disproportionate impact of fines on poor drivers, at least when cities don't scale them to income or offer alternative paths to restitution for people who can't afford to pay and might be sent into a spiral of negative consequences that some argue aren't always proportionate to the crime. And though mobile bus cameras, by their nature, aren't sited on dangerously designed roads that encourage reckless driving, they do sometimes stop on those roads when students live on them, and can divert attention from solving the root problem of deadly road infrastructure.

In New York City, Mayor Eric Adams recently opted not to set up a stop arm camera program on the grounds that not that many injuries are happening because of that particular form of reckless driving.

Territo stresses, though, that there's already good evidence that stop arm cameras works — and that with good AI on board, they can help cities do more than just write tickets.

In addition to identifying dangerous drivers by their face as well as their license plate, potentially someday eliminating the possibility of drivers being cited for crimes that someone else committed with their cars, the company's product can "capture other data and information that can be used by school districts in ... making changes to their pick up and drop off procedures that can add additional safety enhancement." That might look like identifying dangerous road infrastructure in the neighborhoods where their students live, or documenting near-misses in the drop off line that a district might use to make the case for making the streets directly outside schools car-free.

Neither school leaders nor city transportation leaders typically collect that kind of data — and many communities also don't collect fines on any drivers who illegally pass school bus drivers, even when they're rich enough to pay them. And Territo says that's unacceptable.

"We’re always sensitive to the impact a fine may have on the individual who committed the violation," he added. "However, we’re also sensitive to the rights of children, and the rights of parents who are entitled to the peace of mind that their children can ride to and from school safely. It’s up to individual jurisdictions to decide how best to implement these programs. What’s not acceptable is to create or allow an unsafe environment to exist when there are clear solutions to the problem."