Editor’s Note: A version of this article originally appeared on Walk and Bike and is republished with permission.

Recently, a reporter reached out to ask me for my thoughts on the news about the California Air Resources Board’s (CARB) plans to phase-out all new gas-powered vehicle sales by 2035, from a transportation planning lens.

The question, more or less, was whether I think the plan is too aggressive, or whether I thought it was coming too late, considering “the state of things.” As the journalist noted, multiple other countries have already pledged to do this, some of which plan to act on the same time horizon, some slightly faster.

I emailed a response. None of it ended up in the story — which is fine, things change — but since I’d taken the time to put together some thoughts, Streetsblog asked me to share my perspective here.

Considering the urgency of climate change and the many detrimental aspects of our current economic and infrastructure systems, I don’t think that any move to end fossil-fuel dependency is too aggressive. The word “aggressive” tends to connotate an antagonistic element, but we are all on the same side here: we need to keep our cities and towns habitable.

I was born and raised in rural northern California, and even as a child in the 80s, drought was pervasive, particularly in an area with dying timber and ranching industries. Frankly, the timeline that the California Air Resources Board put forward is not particularly fast, considering how rapidly we need action, and how quickly the automotive industry already changes in response to consumer demand – not to mention actively driving demand for certain vehicles.

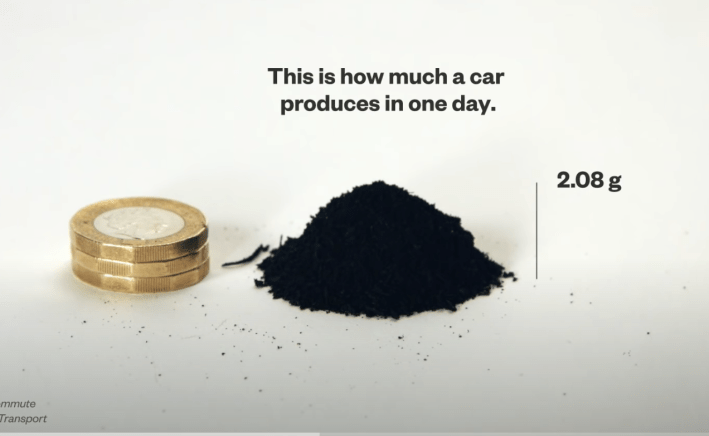

Of course, many people have already noted the many environmental problems that are not solved, but merely changed, by electric vehicles. Those include both the extraction of materials needed for batteries and the challenges posed by their disposal, as well as the large amount of pollution that comes from car brakes and tires, even when those cars are electric.

But even if you could wave a technological magic wand and solve those problems with EVs today, a bigger concern is whether this focus on personal electric vehicles will monopolize public resources that would be much better spent in other ways: namely, on investments in frequent, reliable public transportation between and within cities and towns, better walking and bicycling infrastructure, and land uses that remove the need to depend on vehicles – however they are powered – for every trip.

The problem with a transportation system that depends heavily on private automobiles is that, even if those automobiles no longer emit the same level of greenhouse gasses, they will continue to contribute to unsustainable and sprawling land use patterns, as well as the longer distances and travel times that are bad for us as individuals and communities.

We know that, if people feel they are being more environmentally-friendly with an electric vehicle, they may actually travel more — what we call a “rebound effect.” Perceived or real reductions in personal fuel costs will also result in more travel. And having our communities spread out means more paved surfaces, which means more urban heat, more rainwater run-off, and heavier pollution from the concrete and asphalt industries themselves. It also means longer response times for emergency services, and more time spent in vehicles by everyone, away from family, friends, and healthy activities.

Getting away from gas-powered vehicles is necessary, but not sufficient, for a better environmental future. The best outcome would be using the transition to electric cars as an opportunity to invest heavily in the various types of public transportation that can serve communities from the small and rural to the large urban. And it would also mean changing our codes, standards, and laws to incentivize land uses that support modes of transportation that don’t require automobiles at all.

Dr. Tara Goddard is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning at Texas A&M University. Her research focuses on how the interactions of travel behavior, infrastructure, and culture affect transportation safety, particularly for people who walk and wheel. Follow her on Twitter @DrTaraGoddard.