The debate over how to make electric vehicles loud enough for non-drivers to hear them is missing critical considerations about the disparate impact of noise pollution in poor communities — and raising thorny questions about how to quiet those neighborhoods down without harming the socially and racially marginalized people who live in them.

On Monday, New Yorker author John Seabrook published a 5,000-word longread about what an "9,000 pound electric vehicle" should sound like, chronicling automakers' and regulators' quest to create an "acoustic vehicle alerting system" for notoriously quiet e-cars that "reaches the people who need to hear it, without annoying those who don’t."

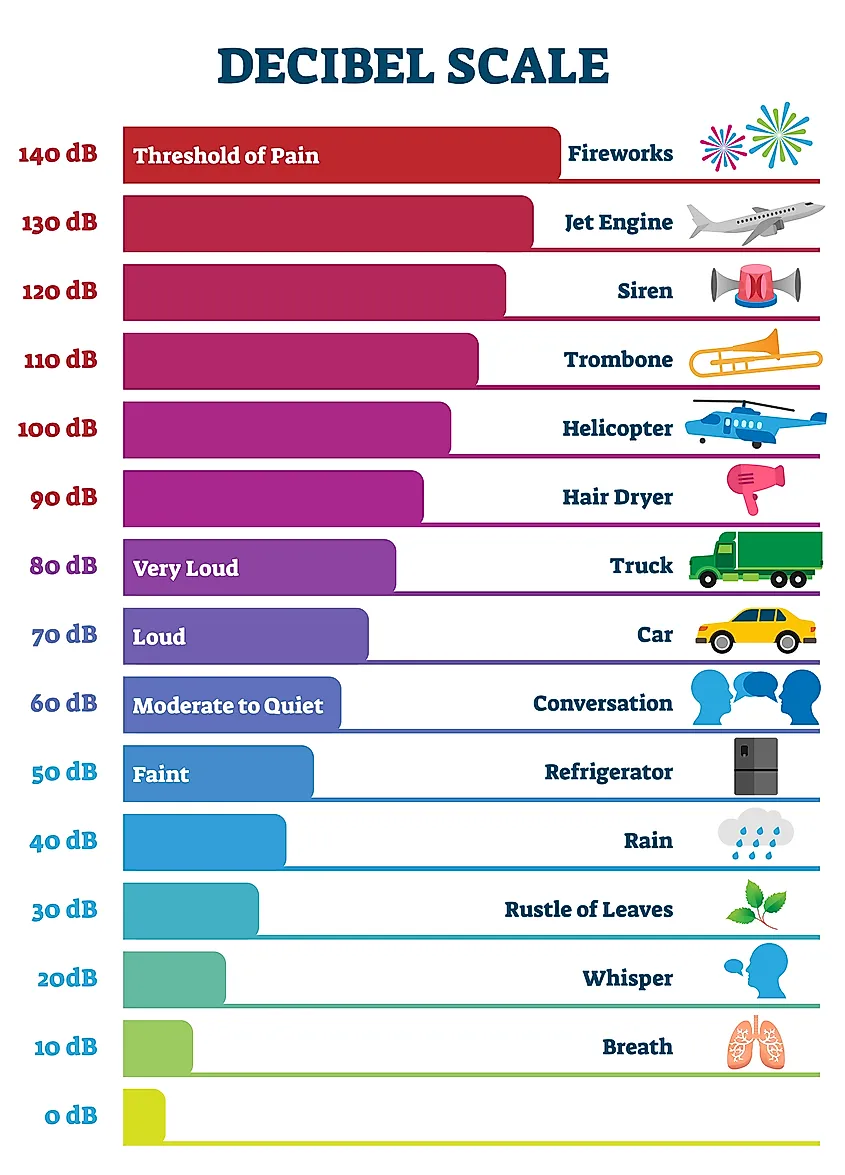

Seabrook's article, though, doesn't discuss the safety potential of having fewer cars in U.S. neighborhoods period — and it isn't until the article's final four paragraphs that any of his interviewees acknowledge that EV alerts are only required to be set to levels "where a normal person would be able to hear it in a normal situation." Douglas Moore, a senior expert in exterior noise at G.M., admits that adjusting those levels to be effective in noisier communities could send automakers, regulators and drivers into a "death spiral of just cranking the levels up" far above the 43 to 64 decibel level currently required by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

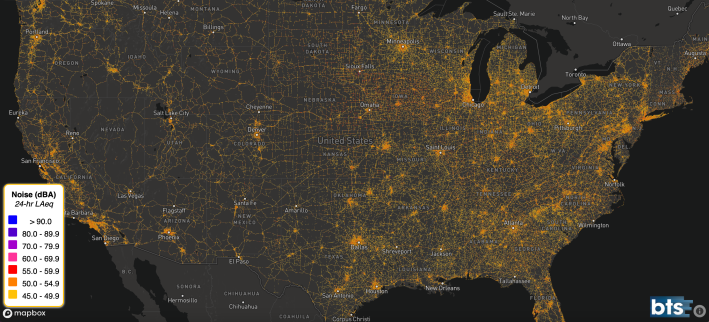

Countless marginalized U.S. communities, though, do not live in such "normal situations" — in large part because of the disparate impact of noise pollution on those vulnerable neighborhoods. And experts say that may not change even if every car on the road were electrified overnight.

Just one day before Seabrook published his column, Dr. Erica Walker published a similar article about how vehicle electrification may not have the major impact on U.S. road noise levels that many pundits assume, particularly in the poor and racially marginalized neighborhoods which are home to the highest concentrations of high-speed roads and highways, as well as the largest quantities of poor-quality pavement. And while her article was geared towards children, it gets at an inconvenient truth that many U.S. adults don't fully understand: how much cacophony cars cause even when they don't have an internal combustion engine.

"If you’re living in a community that has a lot of poor-quality, high-volume roads, it’s going to be loud, period, whether there are a lot of EVs on the road or not," said Walker, an assistant professor of epidemiology at Brown University and founder of the Community Noise Lab. "And communities that live near major modes of transportation, whether it’s highways or rail or airports — these are primarily poor. If there’s a pedestrian-warning system on your car, it’s going to have to be a lot louder [in those neighborhoods] to compete with all of the background noise that’s already there. Whereas if you're driving in a suburb where you can hear the birds chirping, it won't have to be as loud."

Walker explains that as vehicles get faster, the sound of their tires moving along the pavement (and, to a lesser extent, the wind rushing over the body of the car) actually overwhelms the sound of the motor, particularly when driving over a crumbling road. That's why NHTSA currently only requires EVs to emit artificial sounds at speeds lower than 18.6 miles per hour — well below typical speed limits on many U.S. neighborhood streets (though safety experts argue those limits should be higher). It's also just about half the speed limit on many arterials, and a fraction of the top speed on interstates, both which are still routinely run through communities of color.

Even at non-highway speeds, though, traffic noise can cause a raft of health problems, spiking stress hormones that can cause increases in blood pressure and heart rates and weakening the vascular and digestive systems over time. Those maladies only compound when decibel levels don't dip far enough at night to give us a quiet night's sleep, and it can have deadly effects: one study even found that noise pollution shaved “more than three healthy life-years” off the lives of Paris residents before Mayor Anne Hidalgo took aggressive action to combat it.

Walker emphasizes, though, that reducing noise levels equitably isn't always simple. Marginalized people who live in auto-dependent communities often have no choice but to drive, and can't afford electric vehicles, or even newer cars, to replace noisy old clunkers. And even outside of the traffic realm, enforcing acceptable noise levels — not to mention which kinds of noise are considered acceptable — can easily turn deadly, even when police aren't involved.

"When you just say that 'quiet' is the goal, you get conflict," she adds. "In some communities, it’s perfectly okay for people to play in parks until late at night, or to play music on your stoop – that’s the culture. It can be really harmful to erode the acoustic fabric of a community."

Instead of setting punitive policies aimed at shutting neighborhoods up, Walker says policymakers should focus on helping marginalized communities have more of a say in what their neighborhoods sound like. That includes not just measuring and lowering the decibel level on a given block, but actually asking residents what sources of sound they enjoy, in addition to which ones they consider burdensome. (She even developed an app to help do it.)

"I’m a noise researcher, but I’m actually kind of anti-quiet," she said. "I think quiet is an unrealistic ideal ... I try to come from a place of not being 'pro quiet,' exactly, but more 'pro peace' — and specifically, peace that comes through a series of dialogues that weighs all of our acoustic expectations."

When it comes to pedestrian warning systems on electric cars, Walker envisions a world where neighbors might someday be able to decide, democratically, what sounds they want to allow drivers' vehicles to make when they pass by their homes — consistent with expert guidance, of course — and adjust those alerts dynamically to safely compete with the local soundscape. Geofencing technology could someday make this possible, and prevent drivers from selecting their own obnoxious alarms, like Tesla's now-illegal farting and bleating Boombox system.

Until that happens, though, Walker says one of the most powerful ways to quiet a neighborhood is simply adding bike paths and sidewalks, both of which she's found were correlated with lower noise levels. Even those strategies, though, must be deployed in close collaboration with the communities.

"We have to think about communities and the power differentials that exist in them," she added. "The tools that we use to make our soundscapes better have to work for all of us."