Motorists who live in auto-centric cities are generally far happier with their daily commutes than sustainable transportation advocates might assume, a new study finds — and the researchers say that means investments in transit, biking and walking must be coupled with policies that actively disincentivize driving.

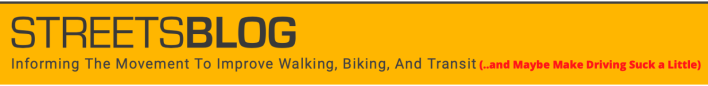

In a 2019 survey of nearly 3,400 people in the heavily car-dependent southern cities of Atlanta, Austin, Phoenix and Tampa released earlier this month, researchers found that respondents who drove for the majority of their trips were significantly more likely to report "satisfactory" daily travel routines than people who relied on active or shared transportation, even when the researchers controlled for demographic differences and lifestyle proclivities.

Moreover, respondents who took the most daily trips in an automobile said they were even more satisfied with their travel choices than those who used sustainable modes a larger percentage of the time.

Of course, it's pretty intuitive that residents of cities that roll out the red carpet for drivers tend to really like driving — and that those forced to get around a human-hostile landscape without a car aren't likely to enjoy the experience very much.

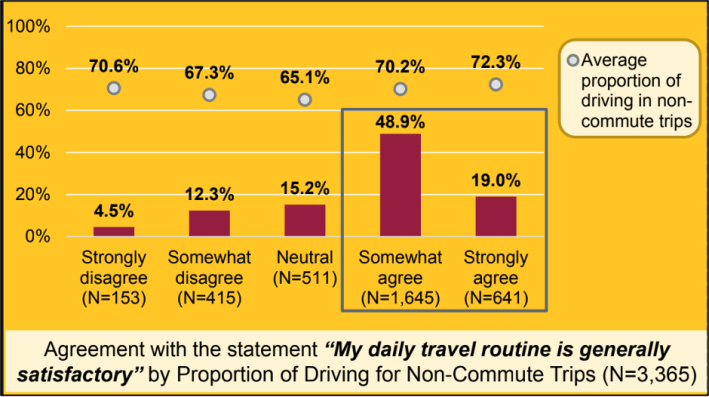

Still, the study authors say some sustainable transportation advocates have struggled to accept this reality, over-focusing on studies that insist that the longer a worker commutes, the less likely they are to be happy with their travel choices — and because 76 percent of U.S. workers drive to work alone, advocates assume, that means most people would be far happier if they had meaningful access to other ways of getting around.

The trouble is, work commutes represent just a fraction of the trips American drivers take every day. And when the researchers asked participants about their satisfaction with their travel routine outside of the daily rush hour crawl, they got a very different answer.

"A narrative we hear quite often is, 'Well, people actually hate being so car-dependent; they hate spending hours and hours stuck in traffic," said Ram Pendyala, director of Arizona State University's School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment and a co-author of the study. "'If only we provided nice alternative modes of transportation, we would see folks shifting in droves!' ... For that strategy to really work, though, we need to prove the original premise that most [drivers] are miserable — and they're not."

Pendyala acknowledges that most U.S. cities haven't made the kind of large-scale investments into transit, biking and walking that many advocates believe would tempt drivers out of their cars. But even in communities that have taken steps to beef up those modes, he says drivers often remain pretty satisfied with their travel choices — and many non-drivers aspire to join their ranks, despite the damage that cars do to the air, the roads, and public safety.

"Even in places where there are pretty good alternative modes of transportation, you generally find a proclivity towards buying a car and using a car and becoming more car-oriented — not less," Pendyala added. "In India, automobile travel is hardly subsidized at all — petrol is $10 a gallon, road congestion is horrendous — and people still express a desire to drive. ... I feel like our profession has been putting blinders on, and saying, 'Oh, if only we stopped subsidizing car-centric lifestyles, all of our problems would be solved.' I don’t think that narrative has served us very well."

That doesn't mean that the fight to end car dependency is hopeless — just that it's far more difficult than simply improving sustainable modes alone. To actually tempt people to make greener transportation choices, Pendyala says policymakers need to look at the fundamental reasons why people choose to get around the way they do, and craft policies to influence them on every possible front. And there are a lot of them.

Namely, he and his colleagues have identified 12 distinct factors that influence mobility choices among road users with various value systems, which he calls the "Dozen C's."

- Convenience, or how easy it is to get where they need to go

- Comfort, both physical and psychological, which includes safety concerns

- Coolness, or how stylish and attractive a mode appears — or how shameful a road user views the alternatives to be

- Cleanliness

- Cost-effectiveness (including time savings)

- Clarity, or how easy and simple it is to utilize a given mode

- Conscientiousness, or how mode choice will impact one's neighbors and community

- Climate-friendliness

- Coverage, or how well distributed access to the mode is across the community throughout the day and night

- Customizability, or how easily the mode can be adapted to a user's unique needs

- Celerity (which is basically a GRE-level synonym for "speed")

In most Americans' minds, Pendyala says cars are winning on almost all of those fronts, with the possible exceptions of conscientiousness and climate-friendliness. (He notes, though, that the latter is shifting as even the most progressive road users embrace the electric car as a silver bullet to decarbonize the transportation sector, despite the fact that it definitively isn't.)

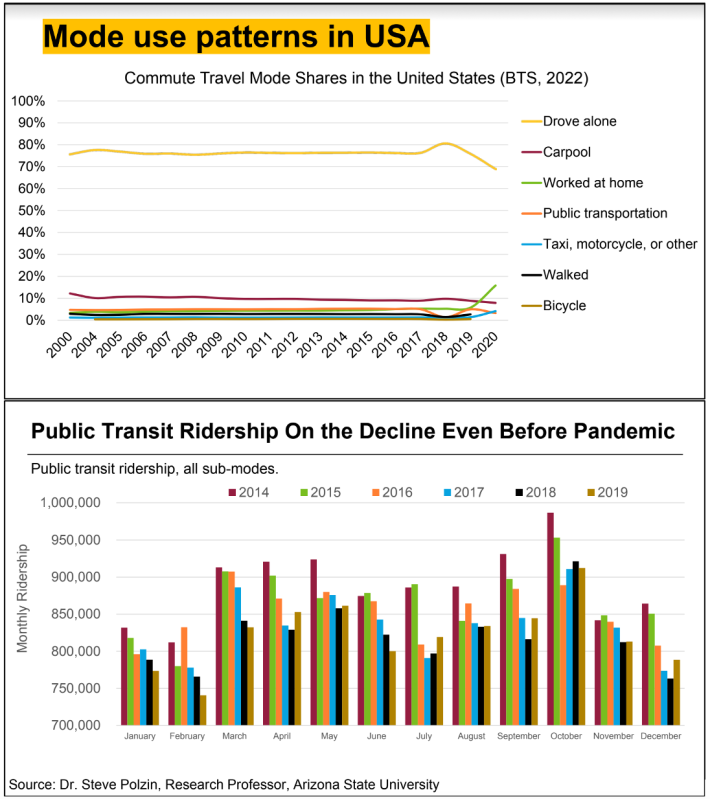

That means it may be necessary for policymakers to emphasize not just less-controversial mode shift strategies — like the improvements to walking, biking, and transit espoused by the tagline of this very website — but also ones that, frankly, make the driving experience worse.

And that includes a lot of politically unpopular strategies such as tolls and fees, limited parking and reducing roadway capacity. Meanwhile, pols would also have to create "planning and zoning policies that promote high-density, mixed-use developments characterized by walkable, transit- and bicycle-friendly environments" alongside investment in sustainable modes themselves — and they'll need to do it in the context of a culture and economy that pours incalculable amounts of money into glamorizing driving and denigrating other modes.

Until we do all those things aggressively — to say nothing of the massive challenges of doing them in ways that don't place even more devastating burdens on the most vulnerable members of society than our current system already does — Pendyala worries that policymakers are doomed to keep doing the easier stuff that doesn't actually get people out of cars. In the meantime, vehicle miles traveled will probably just continue to climb.

"If you look at our track record of decades and decades of attempts to get people to switch modes and reduce car dependency, our profession has largely been somewhat less than successful," he said. "And that's putting it nicely."